Despite obstacles, Native Americans have the nation’s highest COVID-19 vaccination rate

LODGE POLE, Mont. — For the first several months of the pandemic, the residents of the Fort Belknap Indian Reservation were spared by their seclusion in the plains of northern Montana. But when the coronavirus finally arrived, it hit hard.

The six-bed hospital was quickly overwhelmed, and dozens of patients had to be airlifted to Billings or beyond.

By December, 10 people had died, most of them venerated elders, devastating the close-knit community of 4,500. Health workers braced for more contagion and death as the winter forced people into close quarters.

“If you get your electricity shut off or you run out of propane and don’t have hot water, you’re going to Grandma’s house to get cleaned up and stay,” said Jessica Windy Boy, who heads the Indian Health Service branch here.

But the worst fears never materialized. Instead, they helped fuel a highly successful vaccination campaign that has pushed life on the reservation back toward normal.

It’s not just the Fort Belknap reservation that has managed to protect itself. Experts say Native Americans have a higher vaccination rate than any other major racial or ethnic group.

Those rates are difficult to determine, because many vaccine recipients do not provide their race or ethnicity when they get shots. But more than 100 million have done so. That data — collected by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention — suggest that Native Americans are 24% more likely than whites to be fully vaccinated, 31% more likely than Latinos, 64% more likely than African Americans and 11% more likely than Asian Americans.

Data from several states and counties offer supporting evidence. In Alaska, for example, Native Americans make up 15% of the population but as of April accounted for 22% of vaccine recipients.

“The surprising success of Native Americans is encouraging, and I think it can serve as a model for broader vaccination efforts across the country,” said Latoya Hill, a senior analyst at the Kaiser Family Foundation.

The rumors, conspiracy theories and bitter politics that have stalled out the national vaccination effort appear to have gained less currency among Indigenous people.

“We were extremely aggressive with our vaccination rates very early,” said Dr. Loretta Christensen, chief medical officer of the federal Indian Health Service, which provides care to more than half of the country’s 5 million Native Americans. “We had that all on board already, certainly before the Delta variant escalated, so then we’ve kept our cases down.”

Her own tribe, the Navajo Nation, the largest in the country, reports that more than 70% of its members over 12 who live on the reservation are fully vaccinated — well above the rate of 59% for the country as a whole.

“This has been just a tremendous effort across all of Indian Country to take care of our people,” Christensen said.

::

Native Americans often live far from healthcare facilities. They face some of the worst poverty in the nation. And distrust of federal authorities runs deep.

For many experts — and even many tribal leaders — it was hard to imagine a group that would be more opposed to government-backed vaccines.

“There is going to be pushback to this vaccine,” Jonathan Nez, president of the Navajo Nation, told The Times in December.

In a survey last fall — before clinical trial results came out showing vaccines to be safe and effective — only 35% of Indian Health Service field workers said they would “definitely” or “probably” get shots.

But tribal leaders understood that vaccines were the clearest way out of the pandemic. They took to the radio and social media to promote them, warning that elders faced the greatest danger in communities vulnerable due to high rates of diabetes, heart disease and obesity.

They reminded people of the damage COVID-19 had already wrought — killing Native Americans at 2½ times the rate of white Americans — as well as of the smallpox epidemics of the 18th and 19th centuries that decimated many tribes.

“I framed it in the way that the virus was a monster, just like any other monster that has come to plague the Navajo people and wreak havoc,” Nez explained in an interview this week. “I told them that you’ve got to have armor, and the armor is the vaccine.”

By the end of 2020, as vaccines were becoming available, attitudes were changing.

California’s coronavirus case rate remains significantly less than Florida and Texas: two common points of comparison given their population size and different pandemic responses.

In a poll of Native Americans by the Urban Indian Health Institute, 75% of respondents said they were willing to get vaccinated. The primary motivation was “a strong sense of responsibility to protect the Native community and preserve cultural ways.”

Fort Belknap — a 980-square-mile reservation established in 1869 for two formerly nomadic tribes, the A’aninin and the Nakoda — was the first of Montana’s seven reservations to obtain ultra-cold freezers needed to store the vaccine made by Pfizer-BioNTech.

When the first doses arrived on Dec. 16, health workers were swamped with calls from people anxious that shots would run out. A team of nine public health nurses, all raised in the community, took questions on the vaccines by phone and on Facebook Live, assuring everyone that there would be enough.

The centralized structure of the Indian Health Service, often criticized as bureaucratic, allowed the nurses to quickly sort patients by age and find detailed health and contact information.

Tribes that chose to get vaccines from the agency often received them sooner than those that got them from states. Federal officials ditched protocols, letting tribal leaders determine the order of vaccinations.

At Fort Belknap, health workers went first, then essential workers and elders. In an original move, tribal officials also extended eligibility to staff members of nearby schools that enrolled Native children.

“We saved lives doing that,” said Windy Boy, the Indian Health Service executive. “One school off-reservation had a big outbreak in January, after their personnel had one shot on board.”

Aiming to preserve their cultural heritage, nurses also put Native-language speakers ahead in the line. Tribal leaders got shots early to demonstrate that the vaccines were safe.

Nurses drew on credibility from their family ties as they targeted more people to vaccinate. “The patient-nurse relationship is better established because of that trust,” said one nurse, Samantha Allen.

Among the 3,500 tribal members age 12 and above who are served by the Indian Health Service at Fort Belknap, 67% are fully vaccinated, according to the agency office in Billings.

The rate in neighboring Phillips County is 40%.

In the reservation’s annual Milk River Indian Days parade last month, the public-health nurses were declared grand marshals and waved from a float.

“We put on our ribbon skirts,” said Allen, referring to colorful ceremonial attire. “Otherwise we’re always in our scrubs.”

::

The other day in the dusty town known as Fort Belknap Agency, teenagers buzzed past double-wide trailer homes on an ATV.

Gamblers in masks sidled up to the blackjack tables at the Fort Belknap Casino, which recently reopened after a shutdown of more than a year.

Tourists were shopping again at the Kwik Stop convenience store on U.S. 2. Classes were to resume this month at Aaniiih Nakoda College.

It seemed that the reservation had turned a corner.

But the public-health nurses still had work to do. Some people continued holding out on the vaccine.

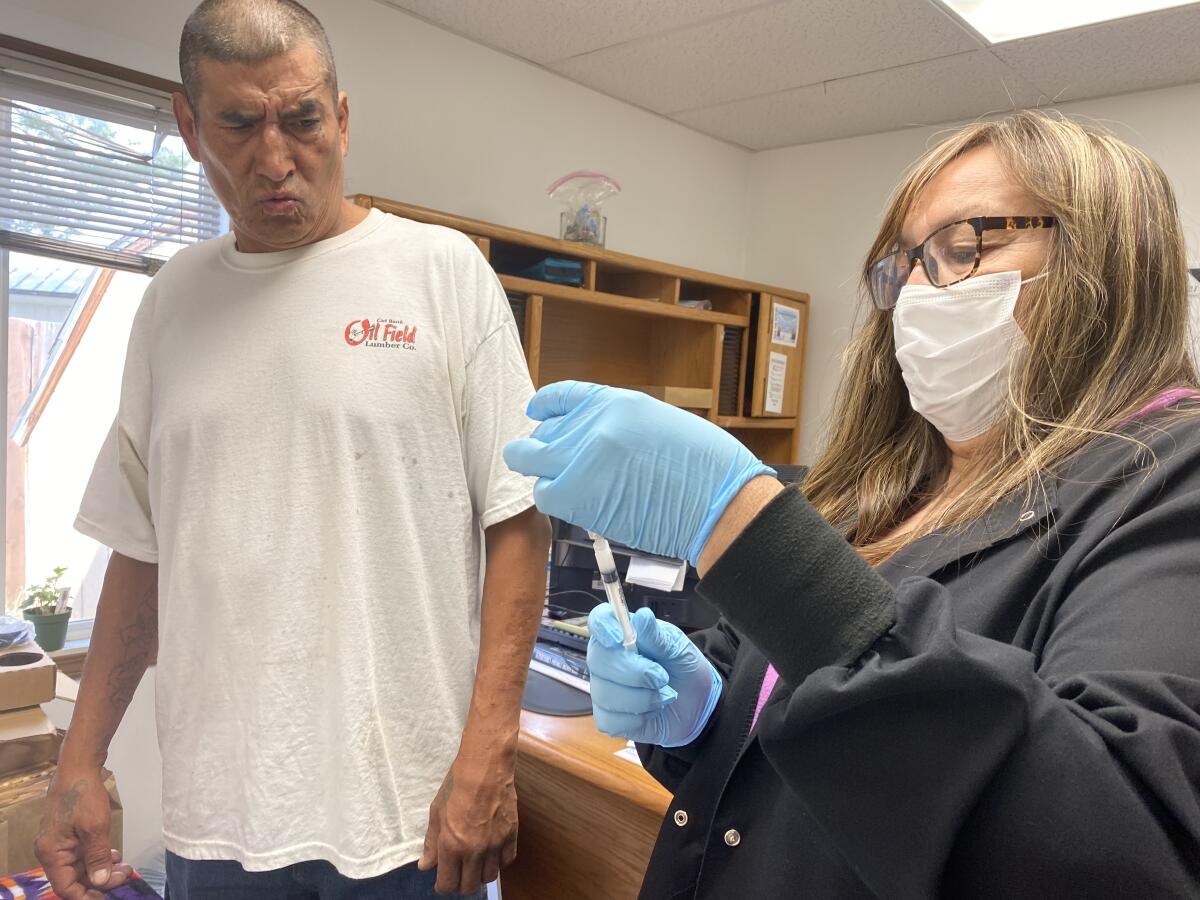

Kathleen Adams, who heads the team, travels around the reservation with vaccines in a cooler, offering to inoculate anybody who still needs it.

“I’ve been asking my cousin and his wife, but they won’t budge,” she lamented.

Then there were people like Marty Lone Bear and his wife, Brittany Allen, who live in a remote spot on the reservation, 12 miles outside the town of Hays.

A community health worker had been urging them to get shots, but Lone Bear didn’t see the rush. His family subsisted on homegrown vegetables and elk that he hunted — and seldom went to town.

“Let’s wait it out and see what the vaccines do to everybody else first,” he told his wife.

But now they had begun to look for work, and their 3-year-old, Bianca, was set to start preschool. That meant more contact with people, including elders.

So last week they caught a ride to Hays, took their seats inside a small clinic and rolled up their sleeves to join the ranks of the vaccinated.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.