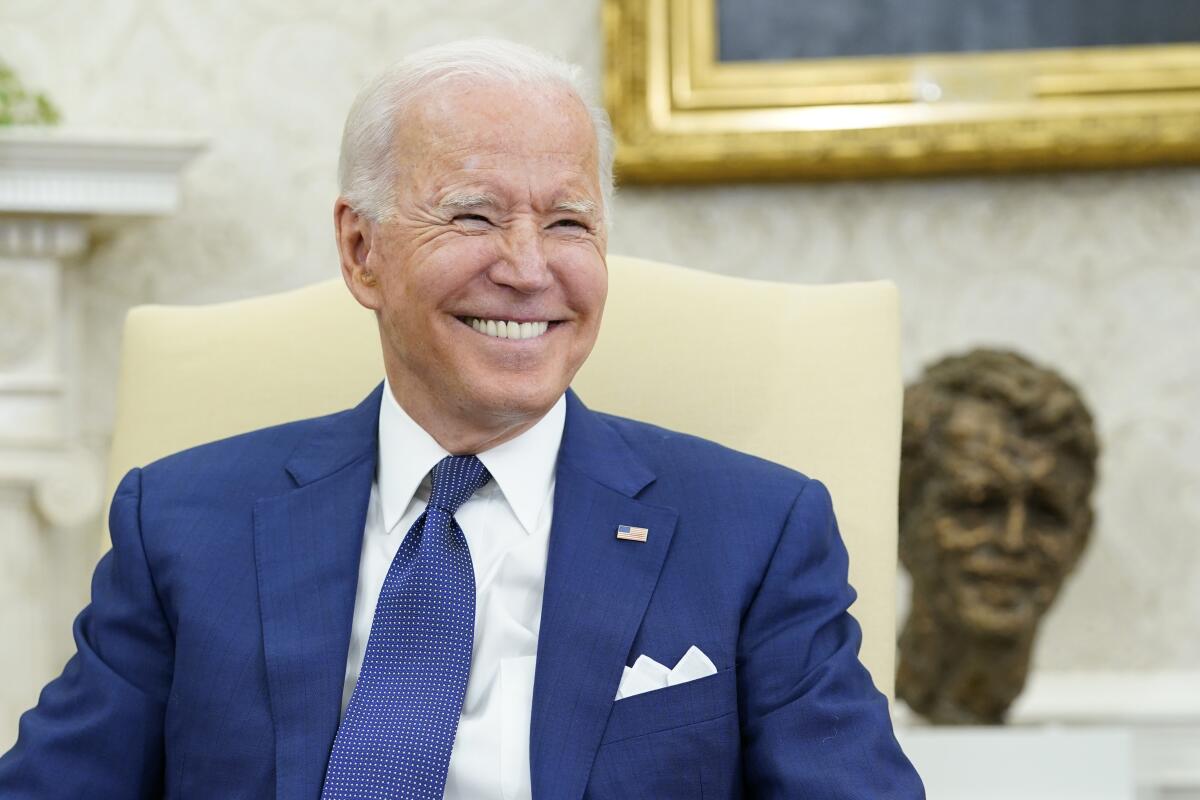

Biden says U.S. combat mission in Iraq will conclude by end of the year

WASHINGTON — President Biden said Monday that the U.S. military’s combat mission in Iraq will conclude by the end of the year, setting out a more precise timeline for American forces to formally step back in their fight against Islamic State militants in Iraq.

The plan to shift the American military mission to a strictly advisory and training one by year’s end — with no U.S. troops in a combat role — will be spelled out in a broader communique to be issued by the U.S. and Iraq after Biden’s White House meeting with Iraqi Prime Minister Mustafa Kadhimi on Monday afternoon. That’s according to a senior administration official, who spoke on condition of anonymity to discuss the still-unannounced plan.

“We’re not going to be by the end of the year in a combat mission,” said Biden, who noted U.S. forces will remain in the country to train and assist Iraqi forces as needed.

“Our shared fight against ISIS is critical for the stability of the region and our counter-terrorism cooperation will continue even as we shift to this new phase that we’re going to be talking about,” Biden added, using an acronym for Islamic State.

The U.S. troop presence has stood at about 2,500 since late last year, when then-President Trump ordered a reduction from 3,000. Biden did not say how many U.S. troops would remain in Iraq when the combat mission is formally completed. The troop reduction may not be substantial because of the continuing advisory and training mission.

The House approved legislation to repeal the 2002 authorization for use of military force in Iraq. It next goes to the Senate.

The plan to end the U.S. combat mission in Iraq follows Biden’s decision to withdraw fully from Afghanistan nearly 20 years after President George W. Bush launched that war in response to the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. Less than two years later, Bush sent troops to Iraq. Biden has vowed to continue counter-terrorism efforts in the Middle East but shift more attention to China as a long-term security challenge.

The senior administration official said Iraqi security forces are “battle tested” and have proved themselves “capable” of protecting their country. Still, the Biden administration recognizes that Islamic State remains a considerable threat, the official said.

Indeed, the militant group is a shell of its former self since it was largely routed on the battlefield in 2017. Still, it has shown it can carry out high-casualty attacks. Last week, the group claimed responsibility for a roadside bombing that killed at least 30 people and wounded dozens in a busy suburban Baghdad market.

The U.S. and Iraq agreed in April that the U.S. transition to a train-and-advise mission meant the U.S. combat role would end, but they didn’t settle on a timetable for completing that transition. The impending announcement comes less than three months before parliamentary elections slated for Oct. 10.

The mission of U.S. forces in Iraq has shifted to training and advisory roles, U.S. and Iraq officials say, but there’s no withdrawal agreement.

“America has helped Iraq,” Kadhimi said. “Together we fight and defeated” Islamic State, he said.

Kadhimi faces no shortage of problems. Iranian-backed militias operating in Iraq have stepped up attacks against U.S. forces in recent months, and a series of devastating hospital fires that left dozens of people dead and soaring coronavirus infections have added fresh layers of frustration for the nation.

For the prime minister, the ability to offer the Iraqi public a date for the end of the U.S. combat presence could be a feather in his cap before the election.

Biden administration officials say Kadhimi also deserves credit for improving Iraq’s standing in the Mideast.

Last month, King Abdullah II of Jordan and Egyptian President Abdel Fattah Sisi visited Baghdad for joint meetings — the first time an Egyptian president has made an official visit since the 1990s, when ties were severed after Iraqi President Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait.

In March, Pope Francis made a historic visit to Iraq, praying among ruined churches in Mosul, a former Islamic State stronghold, and meeting the influential Shiite cleric Grand Ayatollah Ali Sistani in the holy city of Najaf.

The U.S. and Iraq had been widely expected to use Monday’s face-to-face meeting to announce plans for the end of the combat mission, and Kadhimi before his trip to Washington made it clear that he believes it’s time for the U.S. to wind that mission down.

“There is no need for any foreign combat forces on Iraqi soil,” Kadhimi told the Associated Press.

The U.S. mission of training and advising Iraqi forces has its most recent origins in President Obama’s decision in 2014 to send troops back to Iraq. The move was made in response to Islamic State militants’ takeover of large portions of western and northern Iraq and a collapse of Iraqi security forces that appeared to threaten Baghdad. Obama had fully withdrawn U.S. forces from Iraq in 2011, eight years after the U.S.-led invasion.

The distinction between combat troops and those involved in training and advising can be blurry, given that the U.S. forces are under threat of attack. But it is clear that U.S. ground forces have not been on the offensive in Iraq in years, other than largely unpublicized special operations missions targeting Islamic State militants.

Pentagon officials for years have tried to balance what they see as a necessary military presence to support the Iraqi government’s fight against Islamic State with domestic political sensitivities in Iraq to a foreign troop presence. A major complication for both sides is the periodic attacks on bases housing U.S. and coalition troops by Iraqi militia groups aligned with Iran.

The vulnerability of U.S. troops was underscored in January 2020 when Iran launched a ballistic missile attack on Asad Air Base in western Iraq. No Americans were killed, but dozens suffered traumatic brain injury from the blasts. That attack came shortly after a U.S. drone strike killed Iranian military commander Qassem Suleimani and senior Iraqi militia commander Abu Mahdi Muhandis at Baghdad International Airport.

Monday’s communique was also expected to detail U.S. efforts to assist the Iraqi government’s COVID-19 response, education system and energy sector.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.