TOKYO — Thousands of masked Japanese fans filtered into the Tokyo Dome on Sunday night, abuzz with excitement. Those who couldn’t get a coveted ticket milled about outside, soaking in the atmosphere. Deafening pyrotechnics erupted, filling the stadium with smoke.

“More, more, more! Give me a bigger round of applause!” a voice thundered —and the crowd obliged.

The hottest-ticket event in town was off to a raucous start. But it wasn’t the Tokyo Olympics.

The New Japan Pro Wrestling Grand Slam — held before 5,000 enthralled fans at the 55,000-seat arena, the maximum level allowed under the city’s COVID-19 state of emergency — is one example of the strange duality of life in Tokyo during the 2½ weeks the city plays host to the world’s highest-profile sporting event.

With infections on the rise in a fifth wave of coronavirus cases, Olympic organizers decided two weeks before Friday’s opening ceremony that the long-delayed Summer Games would go on but without any spectators. For Tokyo’s 14 million residents, that’s meant a parallel existence with Olympic athletes and other visitors while life largely goes on as before outside the Olympic bubble. Under Tokyo state of emergency measures, alcohol sales are banned and businesses must close by 8 p.m., but live concerts and sporting events are permitted with attendance at 50% of venue capacity up to 5,000 seats.

And so on Sunday night, 20 miles north, Japan’s hugely popular soccer phenom Takefusa Kubo sank a goal just six minutes into the national team’s game against Mexico — to the sparse, if enthusiastic, applause of a few dozen Olympic staff and volunteers scattered across one side of the 63,700-seat Saitama Stadium.

Recorded spectator noise, piped in over loudspeakers by Olympic organizers to mask the deafening silence and make for more customary TV viewing, remained at the same ambient level, indifferent to the dramatic turns on the field.

“It’s very, very disappointing to see such an empty stadium,” said Tasuku Okawa, a Japanese sports journalist who has covered more than a hundred matches at the stadium, which would have been a sea of blue — the Japanese team’s color — were it not for the state of emergency covering Tokyo and surrounding areas.

He remembered being in these stands during the 2002 World Cup co-hosted with South Korea, with Japan’s national team playing Belgium.

“Everybody was standing, dancing, singing,” he recalled. “It was a hugely emotional day, a day I cannot forget for life.” Of today’s young Japanese, he said, “It’s a shame they won’t get to experience it.”

Yuki Kikuchi, a 20-year-old college senior volunteering at the venue, said his friends and especially his father, a devotee of the local soccer team the Urawa Red Diamonds, were incredibly jealous that he was assigned to work at the stadium when Japan was playing.

“Lucky boy,” he said, motioning to himself.

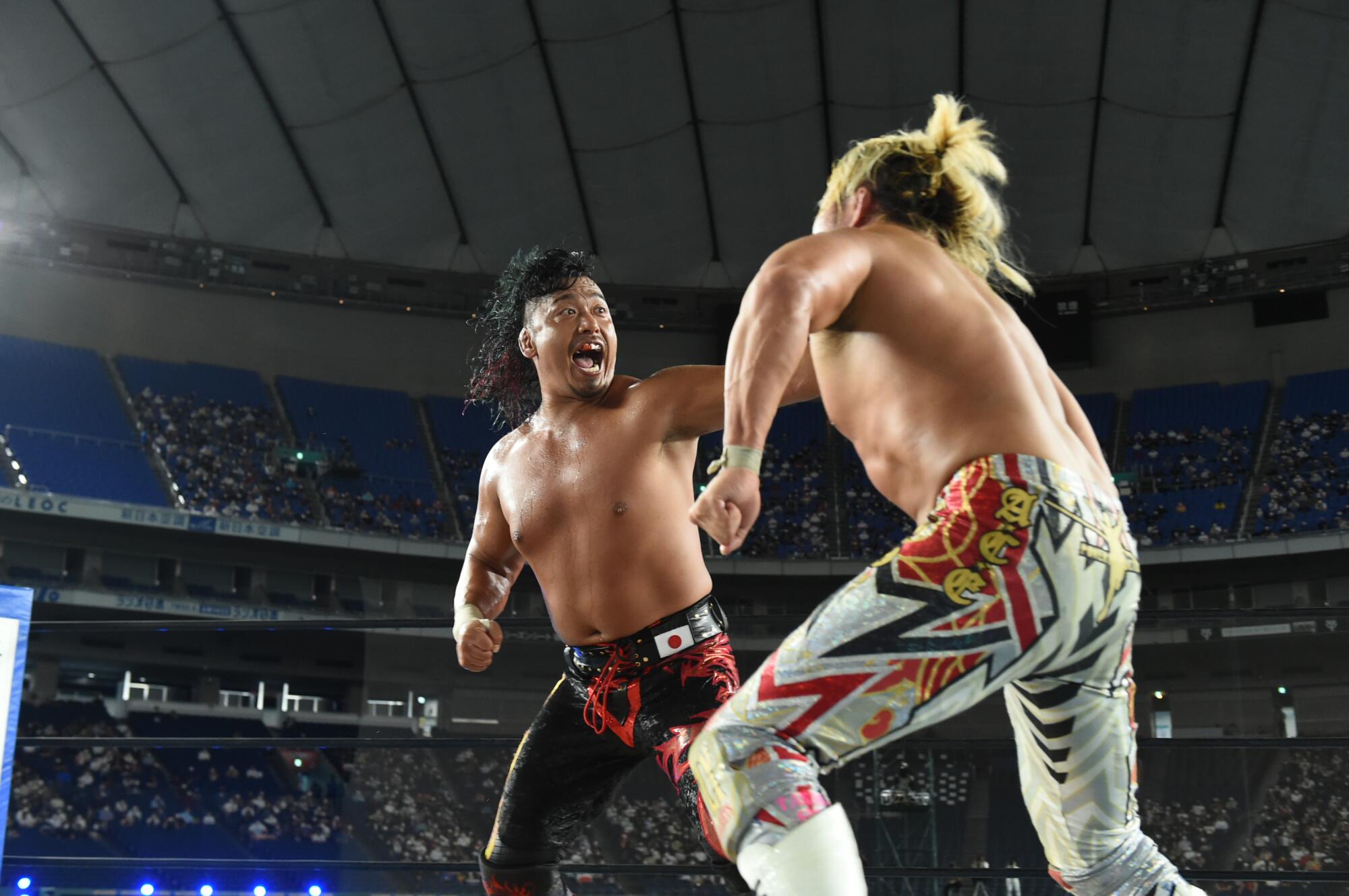

At the Tokyo Dome wrestling event, fans of all ages — from young children to an elderly woman with a walking stick — sat on the edge of their seats, decked out in T-shirts, towels and the required masks, their gear bearing the league’s logo. One especially enthusiastic man was in a full-body red and silver spandex wrestling suit.

“The sound of the fight, the sound of flesh hitting flesh, it is very different when you hear it in person,” said Ryuji Kimiwada, 56, who’d traveled over an hour by train from Saitama to see wrestler Tetsuya Naito, a fan favorite whom Sports Illustrated named as one of its “Top 10 Wrestlers of 2020.”

He’d watched some Olympic softball on TV, he said, but it wasn’t the same as being at a live event.

“There is a kind of wall there between me and the action” when you watch it on television, he said.

Public address announcements repeatedly reminded fans that cheering out loud was banned as a pandemic precaution. Instead, they clapped in time with the wrestlers’ movements or applauded faster and faster in heightened moments of excitement. At a particularly brutal head-butt, the largely compliant crowd couldn’t help but let out a collective “whoa.”

Noburu Ando, 60, said he had no interest in the global sporting event taking place elsewhere in town but was just hoping it would end safely without causing a surge in coronavirus infections. Tokyo has been logging more than a thousand cases a day for the past week, some of the highest levels since January.

As for wrestling, it was always reliable fun, Ando said.

“If you see it directly,” he said, “you will feel its power.”

“I go because it gives me energy,” his friend chimed in. “If there were no spectators, it would be totally different.

Kurumi Sawa, 27, said she was originally more a fan of rugby and boxing but got hooked on puroresu, as professional wrestling is known here, after a friend brought her along to a match.

She had trouble abiding by the no-cheering restriction, a ban instituted since the pandemic began, on Sunday night.

“It’s so dramatic!” she said. “I get excited and it’s hard to keep it in.”

Wrestling fan Farrah Hasnain, 29, a graduate student in Tokyo, had planned to attend the grand slam event but decided not to come because she’d just received the second dose of her COVID-19 vaccine and was concerned about potential side effects.

But she said she felt far safer about wrestling events than she did about the Olympic Games. Athletes weren’t converging from around the world, and she trusted wrestling’s promoters far more than the International Olympic Committee to prioritize safety and to be transparent with fans, Hasnain said.

She fell in love with wrestling because of the aesthetics, costumes and “creative freedom.” At live events, you’re making eye contact with your favorite wrestler, hearing the sounds and feeling the vibrations as their bodies hit the ground with a thud, she said.

“It’s the 4D experience,” she said with a laugh.

The champion of the night’s main matchup was Shingo Takagi, also known as “The Dragon,” a barrel-chested man with a goatee and a mohawk who was clad in red and black tights, the red-and-white Japanese flag on his gold-studded waistband. After defeating rival Hiroshi Tanahashi, he asked the crowd if they’d watched the opening ceremony of the Olympics.

“But today, you all came to pro wrestling, didn’t you!” he roared, to the crowd’s approval, before dropping the mic.

Back in Saitama, Japan pulled ahead by two with a penalty goal from Ritsu Doan mere minutes after Kubo’s score. The team won 2-1, giving away its first goal of the Games at the 86th minute to Mexico’s Roberto Alvarado.

The taped crowd noises abruptly ended with the game, before the players had left the field. Japanese players pumped their fists at the half-dozen team officials in the seats closest to the field.

“The winning team is Japan!” the announcer declared to an empty stadium.

A hushed silence. Then a few cameras clicked away.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.