A century after the Tulsa race massacre, Black residents struggle for a voice

TULSA, Okla. — In the early days of Oklahoma’s statehood, an angry white mob fanned by rumors of a Black uprising burned a thriving African American community in the oil boomtown of Tulsa. Although the area was quietly rebuilt and enjoyed a renaissance in the years after the 1921 race massacre, the struggle among Black people over their place in the city didn’t end.

This month, local and state leaders will formally recognize and attempt to atone for the massacre, which claimed up to several hundred lives, with a series of ceremonies that includes a keynote address by national voting rights advocate Stacey Abrams. President Biden is also coming to the city, the White House announced. But Black Tulsans say that amid the kind words, efforts both direct and subtle still aim to curb their influence and withhold their fair share of power.

Oklahoma history

Before statehood in 1907, Oklahoma was home to Native American tribes pushed out of other regions by white expansion. Then the government decided to open up this land, too, and it became attractive to former slaves who were fleeing persecution in the South. It was also home to Black people who had been brought to the territory by slave-holding tribes.

Some African Americans participated in the land runs in the late 1800s. They included E.P. McCabe, the leader of a movement who hoped to make Oklahoma a majority-Black state free from white oppression.

McCabe “actually recruited Black people to come to Oklahoma on the theory that Oklahoma was the new promised land for these folks,” said Oklahoma historian Hannibal Johnson, author of several books about Oklahoma’s Black history. “Oklahoma didn’t really live up to its billing, obviously.”

Instead, white settlers, many from surrounding Confederate states, poured into the territory, bringing with them the view that Black people were inferior and had to be kept in check. After Oklahoma became a state, the first law approved was a Jim Crow statute requiring segregation of rail cars and depots.

“Oklahoma, in many ways although arguably not a Southern state in terms of racial policy, began to mimic the Deep South,” Johnson said.

The Tulsa race massacre

In the 1920s, as African Americans were migrating from the South during the Harlem Renaissance, Tulsa had a Black community of close to 10,000 people on the north side of the Frisco railroad tracks. The city was flush with money from the booming oilfields, and many Black residents found jobs as hotel porters, car mechanics, laborers and domestic workers. The Greenwood district, known as Black Wall Street, was the wealthiest Black community in the United States, with Black-owned stores, restaurants and other businesses.

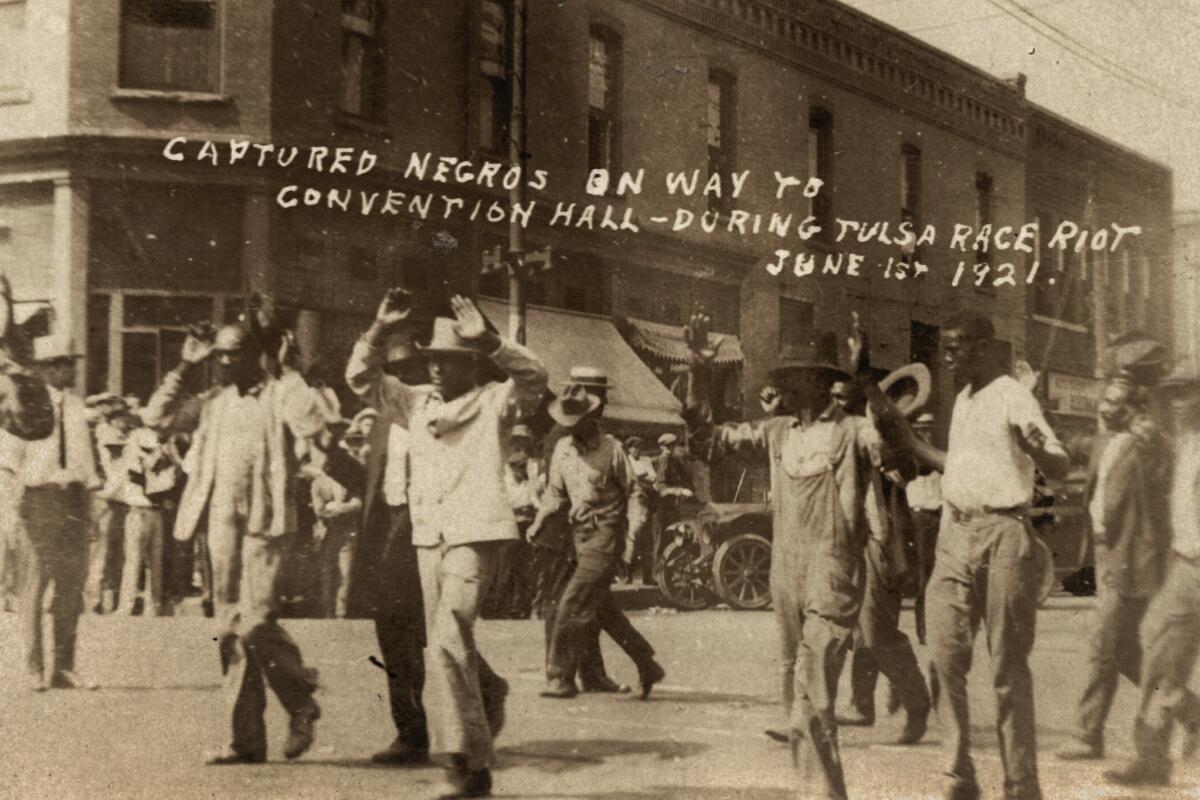

On May 31, 1921, carloads of Black residents, some of them armed, rushed to the sheriff’s office downtown to confront white men who were gathering there, apparently planning to abduct and lynch a Black inmate. Gunfire broke out, and over the next 24 hours, a white mob inflamed by rumors of a Black insurrection stormed the Greenwood district and burned it, destroying all 35 square blocks. Estimates of those killed ranged from 50 to 300.

The Black community now

A hundred years later, African Americans still live on the city’s north side and account for about 16% of Tulsa’s population of 400,000, double the proportion found in Oklahoma overall. The median income of Black households is $25,979, about half that of white households in Tulsa County.

For decades after the massacre, doctors, ministers and lawyers, along with the faculty of Booker T. Washington High School and the publishers of the Oklahoma Eagle newspaper, provided leadership. But Black residents had little say in the city’s government because Tulsa had at-large voting for its city commission. A Black person wasn’t elected to the council until 1990, after a ward system was introduced.

Tulsa’s Black community is now more politically engaged than it once was, according to community activists. In 2020, a 34-year-old Black man who came to Tulsa through the Teach for America program won the Democratic nomination in the race for Tulsa’s congressional seat, and a 30-year-old Black community organizer finished second in the city’s mayoral race.

The killings of two unarmed Black men by white Tulsa law enforcement officers in recent years energized some young Black voters, said Charles Wilkes, a 27-year-old community organizer.

In 2015, a white reserve sheriff’s deputy shot and killed Eric Harris, 44, during an arrest. A year later, police Officer Betty Shelby fatally shot Terence Crutcher, who had his hands raised. Shelby said she thought he was reaching for a weapon.

“We’ve seen shootings time and time and time again,” Wilkes said.

Tulsa’s Black community has seen an influx of foundation and nonprofit funding, much of it for improving public schools and fighting poverty. In 2018, the city was dubbed top in the nation for philanthropy by the readers of the Chronicle of Philanthropy, and Black community organizations have multiplied.

State Rep. Monroe Nichols, a Democrat from Tulsa, says the Black community must now focus on boosting voter turnout — Oklahoma overall had the lowest voter turnout in the nation in 2020.

“I think the interest is there,” he said. “I just think the engagement isn’t there yet.”

Conservative opposition

Oklahoma’s leadership, overwhelmingly white and conservative, is no longer in denial about the massacre of Black Tulsans, which for decades received only a brief mention in state history books.

State and local officials have supported the observance of the anniversary. A new multimedia museum has been embraced as a step toward recognizing the lessons of the violence. Sen. James Lankford (R-Okla.) is a member of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre Centennial Commission.

But atonement for the past hasn’t meant an end to hostility in the present, Black community members say. They cite Oklahoma Republicans’ support for national GOP efforts to limit voting opportunities.

Republican Gov. Kevin Stitt also was a member of the commission, but was removed after he signed a bill to prohibit the teaching of certain concepts of race and racism in public schools.

Meanwhile, the GOP-dominated Legislature has responded to Black Lives Matter protests over social injustice by cracking down on protesters. One new law makes blocking a street a misdemeanor punishable by up to a year in jail. The measure also provides legal immunity in some cases to motorists who run into demonstrators on the road.

“If rioters are surrounding someone’s car, threatening that person, they have a right to protect their family,” said Stitt, who was criticized on Twitter by Martin Luther King Jr.’s daughter for signing the measure.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.