GOP-led states weigh limits on how race and slavery are taught

LITTLE ROCK, Ark. — Complaining about what he called indoctrination in schools, former President Trump created a commission that promoted “patriotic” education and played down America’s role in slavery. But though he’s out of the White House and the commission has disbanded, the cause hasn’t died. Lawmakers in Republican states are now pressing for similar action.

Proposals in Arkansas, Iowa and Mississippi would prohibit schools from using a New York Times project that focused on slavery’s legacy. Georgia colleges and universities have been quizzed about whether they’re teaching about white privilege or oppression. And GOP governors are backing overhauls of civics education that mirror Trump’s abandoned initiatives.

Republicans behind the latest moves say they’re countering left-wing attempts in K-12 schools and higher education to indoctrinate rather than teach students. Teachers, civil rights leaders and policymakers are fighting back, saying students will suffer if states brush over crucial parts of the nation’s history.

“The idea of simply saying you’re not going to use certain materials because you don’t like what they’re going to say without input from professionals makes no sense,” said James Grossman, executive director of the American Historical Assn.

Statehouse fights over what’s taught in public schools are nothing new. Arkansas lost a court battle over a 1981 law that required the teaching of creationism in its classrooms, and in recent years conservatives have waged battles over how evolution, climate change and other topics are taught. But the latest efforts show just how much Trump’s rhetoric on race continues to resonate in the mostly rural and white states he won.

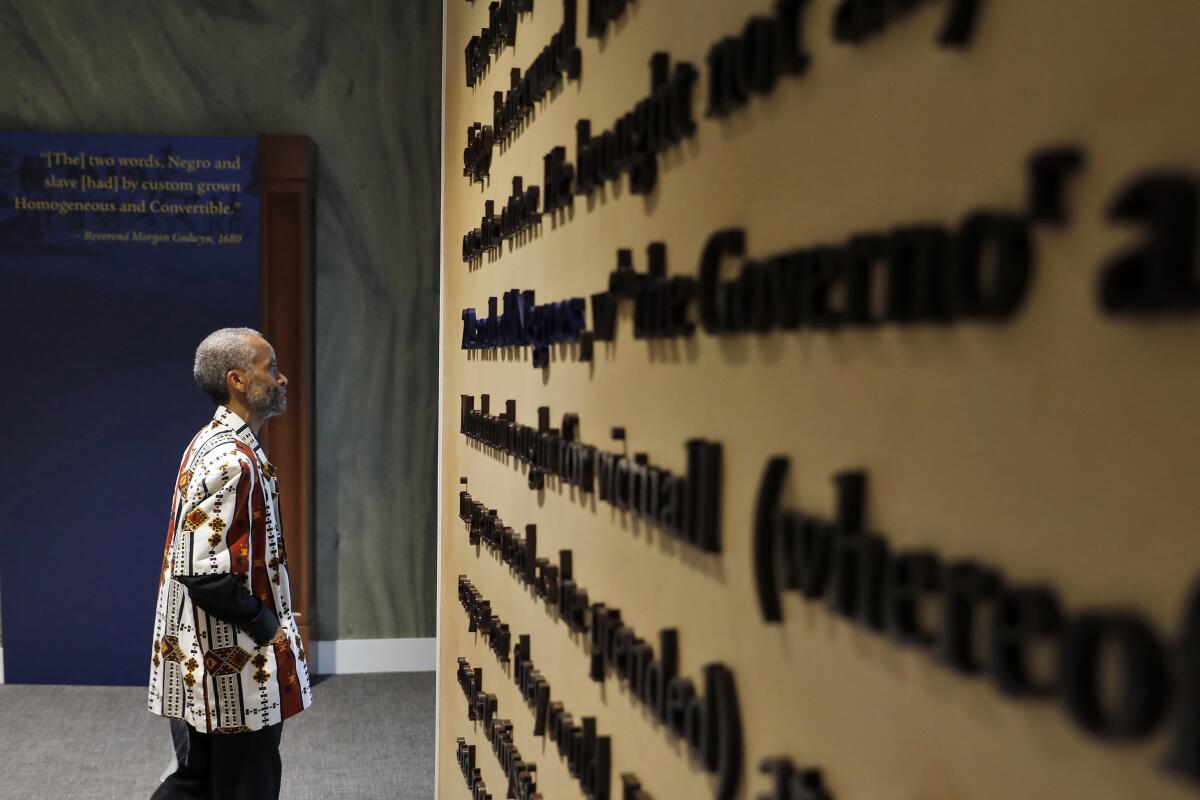

The proposals primarily target The New York Times’ “1619 Project,” which examined slavery and its consequences as the central thread of U.S. history. The project was published in 2019, the 400th anniversary of the first arrival of enslaved Africans. The project was also turned into a popular podcast and materials were developed for schools to use.

A measure pending in Arkansas’ Legislature criticizes the project as a “racially divisive and revisionist account of history that threatens the integrity of the Union by denying the true principles on which it was founded.”

Republican Rep. Mark Lowery, who sponsored the measure, called slavery a “dark stain,” but said the project minimizes the Founding Fathers and cited criticism from some historians about parts of it.

“It should not be taught as history,” he said.

Republican U.S. Sen. Tom Cotton of Arkansas has also been a frequent critic of the project.

Nikole Hannah-Jones, who won a Pulitzer Prize for the lead essay in the project, called it a work of journalism that wasn’t intended to replace what’s being taught in schools. Born and raised in Iowa, one of the states looking to prohibit the project’s use, Hannah-Jones said it’s clear the project is being used to whip up political fears.

“It’s one thing to not like a particular piece of journalism, it’s another thing to seek to prohibit its teaching,” she said.

The Pulitzer Center, which partnered with the Times to develop 1619 Project lesson plans, said it’s heard from more than 3,800 K-12 teachers and nearly 1,000 college educators who planned to use them. Of those, only about two dozen were from Arkansas.

Jonathan Rogers, a journalism teacher at Iowa City High School, said he’s used the project’s podcast in his classes.

Students “definitely responded to thinking about using different sources or alternative storytelling,” Rogers said. “Also, just hearing Black voices is so important when we’re talking about diversity and perspectives, whether it’s historical events or current events.”

Other measures would go even further than targeting the 1619 Project, including a broader bill Lowery said he’s reworking that currently calls for banning courses that promote social justice for one racial group. In Oklahoma, one bill would allow teachers to be fired for teaching that the U.S. is fundamentally racist, or other topics deemed divisive.

Critics say that, besides eating away at local control, the proposals show an unwillingness to address the country’s shortcomings as well as its successes.

“This country does have a history that we have to reckon with and that sometimes our education system glosses over,” said Rep. Emily Virgin, the top Democrat in the Oklahoma House.

After taking office, President Biden revoked the report submitted by the commission Trump formed in response to the 1619 Project. Widely mocked by historians as political propaganda, Trump’s 1776 Commission glorified the country’s founders and played down the role of slavery.

“American parents are not going to accept indoctrination in our schools, cancel culture at work, or the repression of traditional faith, culture and values in the public square,” Trump said when he announced the panel last year.

South Dakota Gov. Kristi Noem, a close ally of Trump’s, last month proposed $900,000 to ramp up her state’s civics curriculum to emphasize the U.S. as “the most unique nation in the history of the world.” Mississippi Gov. Tate Reeves is proposing a $3-million “Patriotic Education Fund” to combat what he called revisionist history.

“Across the country, young children have suffered from indoctrination in far-left socialist teachings that emphasize America’s shortcomings over the exceptional achievements of this country,” Reeves said when he announced it.

In Texas, where academics have long clashed with the state’s GOP-controlled education board on controversies that include lessons exploring the influence Moses had on the Founding Fathers, Gov. Greg Abbott last week told lawmakers that students must learn “what it means to be an American and what it means to be a Texan.” But Abbott hasn’t elaborated on what changes he may seek.

It’s unclear how far these proposals will go, even in solidly red states. Two Mississippi Senate committees ignored, and killed, the 1619 Project ban.

In Arkansas, Republican Gov. Asa Hutchinson has said he believes such issues are usually better addressed locally. He’s asked the state’s top education official to work on alternative legislation that would allow parents to challenge instructional material at the local level.

The proposed limits especially strike a nerve in Arkansas, where divides over race remain more than six decades after the 1957 integration of Little Rock Central High School. Until 2018, the state commemorated Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee’s birthday on the same day as Martin Luther King Jr.

One member of the Legislative Black Caucus said she was worried about the proposal’s effect on the state’s image.

“It will have an economic impact because it will seem as if this state is running from its own history,” said Democratic Sen. Linda Chesterfield, a Black retired history teacher.

Associated Press writers Sean Murphy in Oklahoma City, Ryan Foley in Iowa City, Stephen Groves in Pierre, S.D., Paul Weber in Austin, Texas, and Emily Wagster Pettus in Jackson, Miss., contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.