Who goes first? Oregon vaccine rollout forces stark moral choices

HOOD RIVER, Ore. — As COVID-19 surged, retired attorney Susan Crowley did some simple math and discovered a chilling fact: More than 90% of the people who have died of the coronavirus in Oregon were over 60. So the 75-year-old was shocked when the state started vaccinating teachers this week before senior citizens in a push to get children back into school classrooms.

“I look at these figures and I am literally afraid. It’s not just a question of missing beers with my friends. It’s a question of actually being afraid that if I am not careful, I will die,” she said. “The thing that is so upsetting to me is that seniors don’t matter, the elderly don’t matter. And it’s painful to hear that implication.”

Democratic Gov. Kate Brown has defended her decision, choking up in a recent news conference because she said she “knows of families where 12- and 13-year-olds are attempting suicide” because of social isolation. Meanwhile, her sister, a cancer survivor, is being asked to return to her Minnesota classroom without a vaccine, Brown told the Associated Press.

“No matter what you do, people aren’t happy,” she said. “The teachers in Minnesota are furious at the governor because they are doing seniors first. And here, the seniors are furious at me because I am doing teachers first. There are no right answers, and there are no easy decisions.”

With a mass vaccination campaign underway, the U.S. is facing a moral dilemma as officials from California to New Jersey decide who gets the shots first. Everyone from the elderly and those with chronic medical conditions to communities of color and frontline workers are clamoring for the scarce vaccine — and each group has a compelling argument for why they should get priority.

The current school year ends June 10, and a parent group is pushing for campuses to reopen, but it depends on how quickly teachers can be vaccinated.

Hospitals and medical professionals make such moral decisions when triaging emergency room patients in a disaster or ranking recipients for organ transplants, said Courtney Campbell, an ethics professor at Oregon State University. But what’s happening now is on such a large scale that ordinary people — not just public health officials — are reckoning with questions of who is most important to society and why, he said.

“We’re being asked to emphasize some of our shared national values. ... We’re being called to treat other persons as equals, and that means equals in the sight of the law, but also moral equals, so that matters of privilege or wealth or socioeconomic status get leveled out,” he said.

While the nationwide priority has been inoculating healthcare workers and those in nursing homes, the decisions get more difficult deeper into the vaccine rollout. Federal guidance says states should prioritize the elderly, front-line essential workers and those with underlying medical conditions in the next phases, but ultimately it’s up to state and local officials to decide how to distribute the shots.

Complicating matters is the disarray and confusion that has marked the nation’s vaccine distribution. States have complained about shortages and inadequate deliveries that have forced them to cancel mass vaccination events and appointments.

Originally, Oregon’s governor said teachers and residents over 65 would both be eligible this week but rolled that back because supplies weren’t there. Now, the state’s vaccine advisory committee is wrestling with how to prioritize the next groups.

The state will accelerate vaccine eligibility based on age under new plan announced by Gov. Gavin Newsom.

Oregon is focused on fairness in vaccine access for marginalized communities. Other states, like New Jersey, raised eyebrows by putting smokers toward the front of the line. In Mississippi, authorities are trying to address disparities that show 70% of the vaccine has gone to white residents by establishing a drive-through clinic at a stadium in Jackson, a majority Black city.

Oregon lawmakers of color wrote a letter urging the vaccine advisory committee to prioritize low-income seniors, inmates and front-line workers instead of solely focusing on racial minorities, saying doing so would reach many people of color.

“We are concerned about the way this is being framed and how these groups ... are pitted against each other and against BIPOC communities in general,” the letter said, using an acronym for Black, Indigenous and people of color.

Many teachers, grocers and even some hospital employees are wary of the COVID-19 vaccine and don’t want it. The question of mandatory vaccine requirements by employers is complicated.

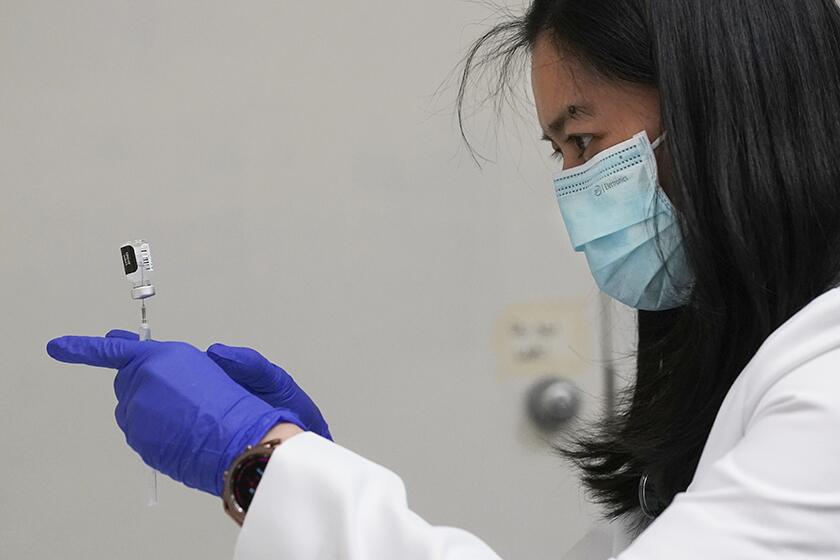

While Oregon health officials grapple with who will be eligible next, vaccines started Monday for teachers and early childhood educators. More than 90% of students have been studying online for nearly 11 months.

Leslie Bienen, a Portland mother of two, has seen her children struggling with online school. When she heard teachers would be vaccinated before seniors, she was torn.

“It’s so complicated. At first, I felt like that is really wrong,” Bienen said. “But if you think of public health as harm reduction, you can’t just think of one thing.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.