As vaccine rollout nears, many concerns raised in Latin America, hard hit by COVID-19

MEXICO CITY — In Latin America, a region hard hit by pandemic, poverty and flawed healthcare systems, many experts fear that large-scale coronavirus immunization campaigns could prove a logistical nightmare, even as vaccinations are set to begin.

Home to 8.4% of the global population, Latin America and the Caribbean account for 30% of the world’s 1.6 million COVID-19 deaths and 19% of the 76 million COVID-19 infections, according to data from Johns Hopkins University and the World Bank.

Mexico and Chile plan to start inoculating health workers by month’s end with the vaccine developed by U.S.-based Pfizer Inc. and its German partner, BioNTech, which is already in use in the United States and Britain. Other Latin American countries are unveiling ambitious plans for large-scale immunization campaigns employing varying vaccines, most still in the testing stage — and virtually all developed in the United States, Europe or Asia.

But healthcare analysts fear that Latin America’s largely ineffective response to the virus could worsen during the massive undertaking of vaccinating hundreds of millions of people. Plagued by severe income inequality, healthcare woes and pervasive corruption, the region appears as ill-prepared now as it was when the virus first struck early this year.

“The management of the pandemic has been so bad that we are not optimistic about how the vaccine is going to be managed,” said Dr. Francisco Moreno, who heads the COVID-19 unit of Mexico City’s private ABC Medical Center, which, like most other hospitals in the capital, has no more available beds for COVID-19 patients. “The people at the top are not doing what has to be done.”

Amid soaring numbers of cases, officials Friday declared the entire Mexico City metropolitan area — home to more than 20 million people — a “red” zone, shutting down nonessential activities and silencing busy streets.

Meanwhile, complaints of inadequate equipment, insufficient drugs and other essential items have escalated anew.

“We are living in a catastrophe right now — we have patients sharing one tank of oxygen and there is a shortage of everything: ventilators, beds, medicines, safety gear, medical personnel,” said Claudia, a veteran doctor at a public hospital in Mexico City who asked that her surname be withheld, fearing reprisals. “I have faith in the effectiveness of the vaccine. But I have no faith in the abilities of authorities to handle the logistics of vaccination, because they have demonstrated that they are not capable.”

With so much uncertainty, officials across the region are moving to dampen expectations of a quick fix. Many people may have to wait until 2022 for vaccines.

“We must be patient and remain realistic that COVID-19 will be among us for some time — so our work to control it cannot and must not stop,” Pan American Health Organization Director Carissa F. Etienne told reporters last week in Washington.

Mexican authorities anticipate an initial delivery of 250,000 doses of the Pfizer-BioNTech formula this week. Officials immediately plan to begin inoculating more than 6,000 people a day, starting with medical workers. The vaccine’s intricate requirements — including two shots per patient three weeks apart, and ultra-cold storage of the vaccine at temperatures of less than minus 76 degrees Fahrenheit — pose a challenge to the region’s frayed infrastructure. Mexico intends to use military personnel and facilities for its vaccine launch.

Further complicating matters, Mexico and other nations have committed to purchasing more than one vaccine, often featuring different storage, dilution and dosage guidelines, and produced in different parts of the world.

Relatively well-off countries like Mexico, Brazil and Chile have already earmarked billions of dollars for vaccine purchases, hustling to cut bilateral deals with manufacturers in a free-for-all in which money talks.

To help score vaccines, Latin American nations have been serving up volunteers to international pharma giants for late-stage trials.

“This was my way of helping out,” said Johana Ramírez Cuevas, 34, one of more than 6,000 Mexicans who have received experimental doses from the Chinese firm CanSino Biologics, with which Mexico has a pre-purchase deal to buy shots for 35 million people. “I was very nervous.… But I feel well. I’ve had no after-effects.”

Some impoverished countries — including Bolivia, El Salvador, Honduras and Nicaragua — are counting on free vaccines via Covax, an international consortium backed by the World Health Organization. But doubts remain about whether Covax will have enough funding to assure equitable dissemination of vaccines.

The British drug maker AstraZeneca has cut production deals with Brazil, Argentina and Mexico, including a cooperative project with Carlos Slim, the Mexican billionaire. But the AstraZeneca injection, developed by researchers at Oxford University, remains in the clinical-trial stage.

Graft is another problem for the vaccine effort. Investigations throughout the region have uncovered evidence of price-gouging for purchases of test kits, ventilators, medicines and other essential equipment — along with lucrative contracts and kickbacks for politically connected COVID-19 scammers.

“We think what has happened with tests, with ventilators, with medications will happen again with vaccines,” said Dr. Suyapa Figueroa, president of the Medical College of Honduras. “The consequence will be more deaths.”

In addition, Interpol issued a global alert this month warning about organized criminal efforts worldwide to hijack vaccine shipments or traffic in false cures.

Even before the inoculation stage, vaccine policy has become embroiled in regional politics.

Argentine President Alberto Fernández has come under fire for turning to Russia’s Sputnik V vaccine to inoculate 10 million people. The president vowed to be the first vaccinated “so that no one need to be afraid.”

Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro, a right-wing populist and longtime coronavirus skeptic, has declared that he has no intention of getting vaccinated — though Brazil ranks second in worldwide COVID-19 deaths, after the United States, with more than 185,000. Bolsonaro, who tested positive for the virus in July but who has continued to downplay its risks, assailed a health ministry decision to purchase 46 million doses of the CoronaVac vaccine from the Chinese company Sinovac Biotech. He said he didn’t trust Chinese remedies.

Last week, Bolsonaro publicly ridiculed the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine, joking that it could turn people into alligators, cause women to grow beards and men to speak effeminately.

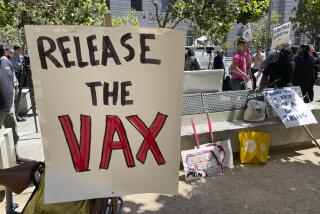

Many fear that Bolsonaro’s scorn could bolster the anti-vaccine movement in Brazil and elsewhere. There is already considerable public skepticism. Almost half of respondents to poll this month in Mexico’s El Financiero newspaper said they had little or no faith in the vaccines.

But for many, the prospects of a vaccine are stirring fresh hopes.

Karla Salgado, 35, a single mother of two, was among more than 100 people waiting in the morning chill for free COVID-19 tests in the central plaza of Iztapalapa, a densely populated swath of Mexico City hard hit in the pandemic. A cashier at a grocery store, she had recently experienced headaches, a cough and fever.

“I’m concerned about infecting my family, but also about losing income — I can’t afford not to work,” Salgado said. “As soon as the vaccine arrives, I’m signing up for it — that’s the best thing that could happen.”

As Mexico’s COVID-19 caseload soars, the country’s hospitals, cemeteries and crematoria are jammed. Each day brings a new public account of relatives in desperate searches to find treatment for infected loved ones.

Likewise, the kin of the deceased must shop around to find final resting places.

On a recent afternoon at the St. Nicholas of Tolentine cemetery in the Iztapalapa district, Rosalía Benhuema, 55, awaited the arrival of the remains of her niece, Rubí Benhuema, 27, a coronavirus victim. There was no room in the cemetery in her hometown of Chalco, 25 miles away.

The niece, a hairdresser, was a single mother of a boy, Amir, 4. She went house-to-house to style clients’ hair. She likely became infected while visiting a customer’s home.

“We came because we are family,” the aunt said. “We want to tell the parents of Rubí and grandparents of Amir that we love them, and we are here for them at this most difficult moment.”

Contributing to this report are special correspondents Cecilia Sánchez and Liliana Nieto del Río in Mexico City, José Maria Álvarez in Oaxaca, Paulo Cerrato in Tegucigalpa, Honduras, and Andrés D’Alessandro in Buenos Aires.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.