New York and the crisis in mass transit systems

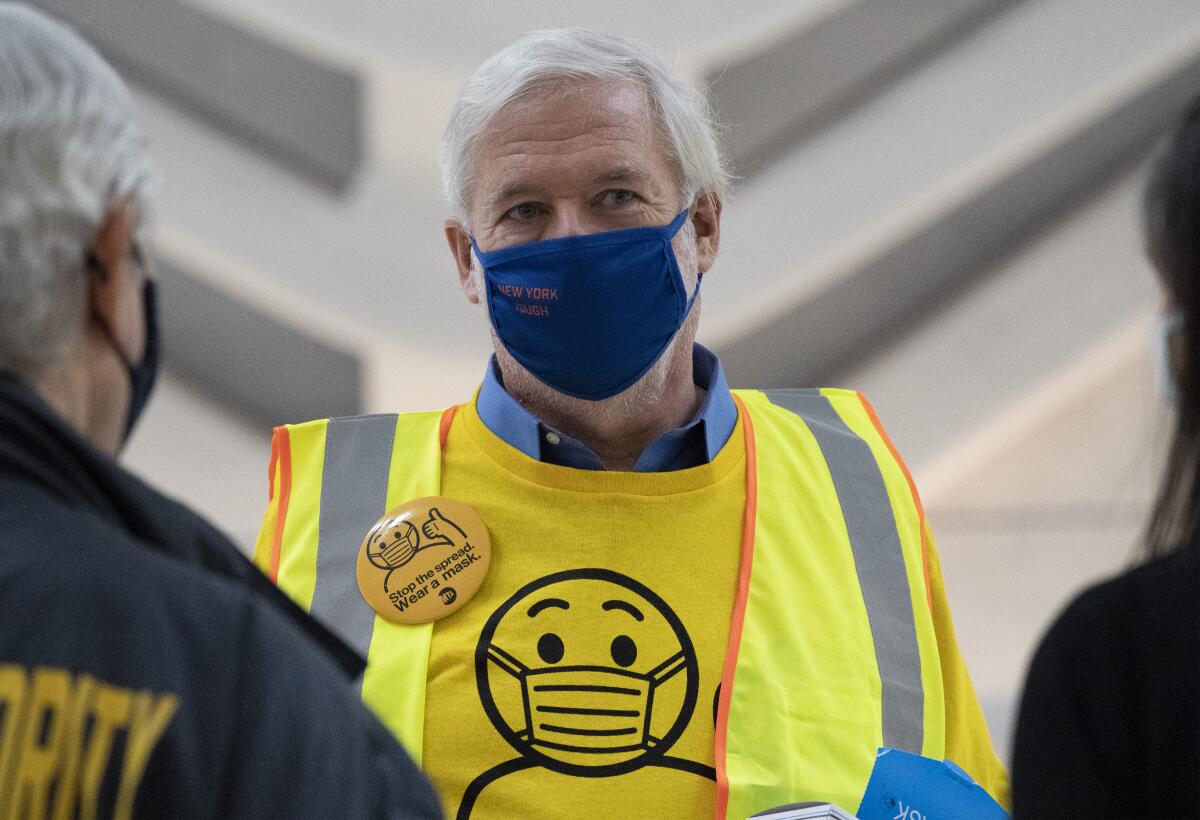

NEW YORK — Patrick Foye travels to work on the Long Island Rail Road, once known as the “Route of the Dashing Commuter.” He boards the 6:45 a.m. from leafy Port Washington, disembarks in the catacombs of New York Penn Station and then rides the subway to his office on the tip of Manhattan.

As chief executive of the New York region’s public transportation agency, Foye’s vinyl seat provides a stark view of the effects of the coronavirus crisis. The parking lots at Port Washington are plains of empty asphalt. The LIRR’s rail cars are carrying a quarter of their normal daily load of more than 300,000 passengers. Office workers no longer dash — they Zoom.

A collapse in fare and tax revenue has opened a $12-billion fiscal hole at his New York Metropolitan Transportation Authority. It has an annual budget of $17.2 billion, of which fares make up $6.5 billion and taxes another third. Without more aid from Congress, Foye may furlough 8,000 employees, eliminate billions of dollars of planned capital spending and gut service on New York subways, buses and railways, including the LIRR.

Yet an even more ominous prospect looms in the longer term: after COVID-19, what happens if some passengers never come back? It’s a question echoing across cities around the world, from New York to London — where leaders just agreed a $2.4-billion short-term transport rescue deal — to Singapore.

The pandemic is setting in motion structural changes in how employees do their jobs with profound implications for urban settlement, transport networks and energy use. Journeying to work five days a week now seems excessive in an age of video conferencing and cloud data. In the future, 85% of employees would prefer to work remotely at least two to three days a week, according to a survey by CBRE, the commercial real estate services company.

Such a scenario could seriously weaken the finances of public transit systems that underpin great cities. No other mode of transportation can efficiently deliver millions of workers into dense central business districts. With fewer riders and fares, transit operators face an unpleasant choice: trimming service, which repels customers, or going cap in hand to the government for more subsidies.

Foye still hopes to stave off an immediate funding crisis with federal coronavirus aid. But he is also pondering how he would respond to lasting changes in commuting habits.

We “would have to think about right-sizing service and taking steps to reduce the cost to get it commensurate with the long-term decline in revenue,” he said.

Driving revival

Passenger numbers collapsed when authorities declared lockdowns in the spring, keeping all but essential workers home. After partially reopening in the summer, New York City is placing more limits on social gatherings and restaurants to keep a lid on climbing coronavirus cases.

Initial research suggested that transit seeded the disease, spreading it through city arteries. But later studies, some sponsored by transportation agencies, found that buses and trains with proper safety measures were no more risky than offices and homes. Transit lines adopted aggressive cleaning routines, with the MTA shutting down New York subways overnight for the first time in history to allow daily disinfections.

Suburban railways lost the most trade as white-collar workers and students worked remotely. Buses have regained about half the passengers they had before the first outbreaks, reflecting demand from those with fewer options. The “transit-dependent” tend to have lower incomes, are more often people of color and include some of the essential workers keeping hospitals, kitchens and warehouses open during the pandemic.

As more affluent office workers desert transit, they may be less willing to see taxes support it. “If and when we resume a semblance of normalcy, will the affinity to public transportation still remain? That’s a bigger question that nobody has the answers to. So far it doesn’t seem like that,” said P.S. Sriraj, director of the Urban Transportation Center at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

The federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention gave cars a boost when it recommended that employers subsidize workers to drive alone. Although car traffic disappeared in the spring, reducing urban pollution, it is now back to about 80% of pre-pandemic volumes in metropolitan areas including Boston, Chicago, Los Angeles and New York, according to GPS data compiled by Inrix, a transport information company.

The return to cars was visible on Manhattan’s west side during a recent afternoon rush hour. Traffic crept for blocks towards the jammed mouth of the Lincoln Tunnel to New Jersey. A few blocks away, train announcements echoed across a nearly empty Penn Station, where new touchscreen vending machines sell masks and hand sanitizer.

Green transport advocates warn that the driving revival will lead to “carmageddon” on crowded streets. Globally, oil demand could increase by 600,000 barrels a day — about 0.6% of pre-pandemic consumption — over the next couple of years as people abandon mass transit for private cars, the International Energy Agency has forecast. Although it also calculates that fuel saved by remote working could eventually offset about 250,000 barrels a day of that extra demand.

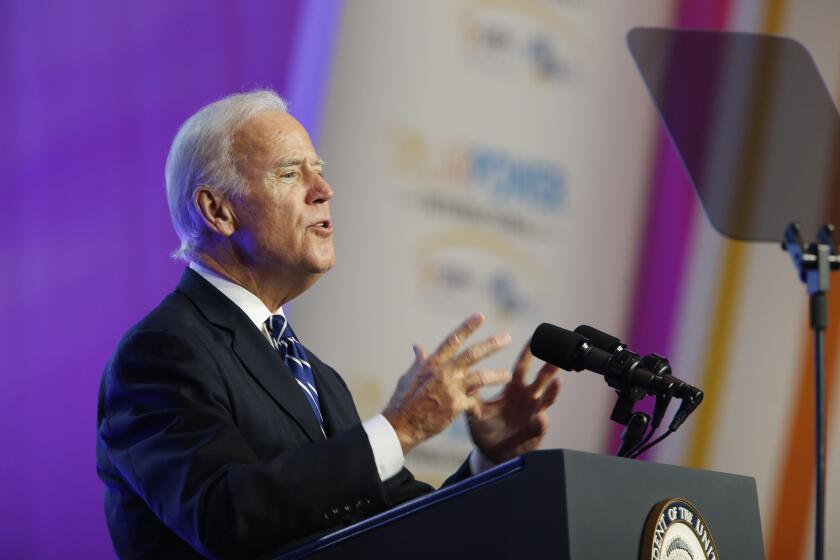

President-elect Joe Biden has featured “high-quality, zero-emissions public transportation options” as part of his plan to address climate change.

“It’s important to preserve or reinforce the priority of public transport if we want to avoid complete gridlock in cities,” said Mohamed Mezghani, secretary-general of the Brussels-based International Assn. of Public Transport. “We need to make sure that people will not go back to their cars.”

Rotating workers

Public transport experts hotly debate the extent to which remote working habits will stick. At a recent online forum, transit professionals were among the hundreds who heard James Hughes from Rutgers University suggest that a revolution is under way.

“This is now a watershed moment in the world of work. The coronavirus shock may have exposed an outmoded white-collar workplace structure,” he declared. “Work is now being recognized as much more of an activity, rather than as a place.”

Hughes, a veteran urban planning pundit who witnessed New Jersey’s rise as a sprawling corporate hub, envisaged a new, decentralized office geography where workers gathered together only when they needed to.

“I think it was probably a major market failure that work as a place remained so dominant for so long,” Hughes said. Endangered, he added, was “the ritual of commuting five days per week to large centralized headquarters … simply to be crammed cheek by jowl in a sea of office workstations.”

The forum’s co-sponsor was New Jersey Transit, the third-largest transit network in the U.S. by passenger numbers with services feeding New York and Philadelphia. The agency’s trains are running at 20% of pre-pandemic volumes, while bus passenger numbers are down by half.

Kevin Corbett, New Jersey Transit’s chief executive, sounded a defiant tone at the forum.

“I believe transit will come back very strong,” he told the virtual audience.

Later, in an interview with the Financial Times, Corbett spoke about the years after the 9/11 terror attacks, when he helped manage lower Manhattan’s economic recovery. People at the time questioned the future of the skyscraper. Now super-tall condominiums tower above the city, he said. Until February, New Jersey Transit was operating standing-room-only trains, delivering many of the 2 million people entering Manhattan every day.

Recent reports of local road congestion give him a perverse comfort. “When I hear now that [delays into] the Lincoln and Holland tunnels are 20 minutes or a half-hour, or there’s an accident and it’s 45 minutes, sort of like the old days, that’s a big factor in driving people back to us,” he said.

Remote working, however convenient, will not predominate, he believes.

“If there’s a down cycle in the economy, people may feel a little bit more comfortable if they’re in the office [being seen] than if they’re working remotely,” he said.

Unsurprisingly, landlords share his optimism. When Douglas Durst was named chairman of the Real Estate Board of New York in September, he said his family’s company had lasted more than 105 years, “and this is not even our first pandemic — we survived the influenza pandemic of 1918.”

Yet videoconferencing was science fiction then. Kelly Steckelberg, chief financial officer of web conferencing company Zoom Video Communications, told an online investment forum that only 4% of her employees wanted to go back to the office every day, “and when I’ve talked to peers with other companies, that’s really consistent with what they’re saying.” Zoom’s share price has sextupled to more than $400 this year.

Employers are already making decisions that will have lasting effects on commuting trips. JPMorgan Chase’s headquarters rises just north of Manhattan’s Grand Central Terminal. The financial giant’s corporate and investment bank will now be rotating its more than 60,000 employees in and out of offices across the world.

“We are going to start implementing the model that I believe will be more or less permanent, which is this rotational model,” Daniel Pinto, the bank’s chief operating officer, told CNBC. “Depending on the type of business, you may be working one week a month from home, or two days a week from home, or two weeks a month.”

Some companies are exiting the city completely. After the geothermal heating and cooling company Dandelion Energy was spun out of Google’s advanced research lab, Chief Executive Michael Sachse rented offices a block west of Grand Central station. To get to work, “everybody was taking public transit. It didn’t make any sense to drive to Midtown,” he said.

He closed the office when the coronavirus hit, leaving two equipment warehouses outside the city as the company’s only physical locations.

Kevin Krumm’s tech recruitment company Objective Paradigm recently signed a 10-year office lease adjacent to a section of the Loop, the elevated train tracks of Chicago’s central business district. But now some of his clients are seeking new recruits who can be based anywhere. “You don’t have to be within a commutable proximity. I feel like that’s a big shift,” Krumm said. “I feel like this whole talent, geography, labor-cost arbitrage is underway.”

$25-billion bailout

It is an arbitrage with dire implications for transit agencies rooted in their regions. The Chicago Transit Authority’s bus and rail services are running at more than 60% below normal. The Metra rail system, which operates 242 stations on 11 rail lines that run in spokes to Chicago suburbs such as Winnetka and Naperville, has slashed its schedule in the face of a 90% collapse in passengers.

Car traffic on the Chicago-area roadways is now just 10 % below levels in February, according to the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning. The Regional Transportation Authority, which allocates funds to Chicago-area transit agencies, examined six COVID-19 recovery scenarios and found that commuting by transit decreased in each one. At stake is $30 billion in capital investment needs over the next decade, such as new buses and fixing bridges.

“Aspects of telework are here to stay,” said Leanne Redden, RTA’s executive director. “They were here pre-COVID, and it’s become much more obvious during COVID.”

U.S. transit agencies are public bodies funded by a mix of fares and subsidies from taxes, highway tolls and other sources. Falling passenger numbers and the pandemic economy have dealt blows to both sources of revenue. The decline in fare, toll, tax and other subsidy revenue is estimated at $6.9 billion this year for New York’s MTA, according to a study by New York University.

Such transport operations have been kept afloat thanks to $25 billion from the federal CARES Act coronavirus bailout, but the money will run out for most agencies next year. Democrats in the House of Representatives included $32 billion more in transit funding in their proposed stimulus bill, but the legislation has stalled in a stand-off with Republicans who oppose aid to state and local governments, including public transit bodies.

“New York risks losing its place as a preeminent global city” without adequate transit funding as service and maintenance cuts trigger a “continuous cycle of decline,” the Regional Plan Assn. warned in a report published in October on the city’s future. But the public policy group, with a board made up of corporate, legal and property executives, rebutted a narrative that New York is spiraling downhill.

Transit agencies were already contending with threats from ride-hailing services before the pandemic. Now, experts are talking about reinventions for a work-from-home world, such as ticket prices that reward less frequent travel and better service outside of traditional rush hours, even if peak service is cut.

“The transit system is going to have to adapt to the modern workforce,” said Mitchell Moss, director of the Rudin Center for Transportation at New York University.

The more urgent focus is surviving until a mass vaccination program gets the go-ahead. Last week, Boston’s transportation authority proposed sweeping service cuts, saying that nearly empty trains, buses and ferries were a waste of money. Moss co-wrote a study that warned that 450,000 jobs could be lost in the New York region if Congress fails to give the MTA $12 billion more in aid.

Foye, who commutes from Long Island in a blue surgical mask, said: “I’m bullish on the city and state in the intermediate and the longer term. Cities like New York and London and Rome and Bombay have over a period of centuries endured pandemics and survived.”

But he said of commuters, “I don’t think they are all going to come back.”

© The Financial Times Ltd. 2020. All rights reserved. FT and Financial Times are trademarks of the Financial Times Ltd. Not to be redistributed, copied or modified in any way.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.