Trump will leave office foiled by the North Korea nuclear problem. Will Biden fare better?

SEOUL — President Trump’s cool-headed nuclear envoy told the North Koreans it was “a window of opportunity.”

Here was a U.S. president willing to venture far outside traditional diplomacy, particularly with regard to a pariah nation like North Korea. As quick as he was to fire off insults on Twitter and threaten “fire and fury,” Trump stunned many by agreeing to meet with leader Kim Jong Un — even stepping onto North Korean soil when he crossed the demilitarized zone between the two Koreas.

“You know how to reach us,” said Stephen Biegun, now the deputy secretary of state, in late 2019. But at the end of all the photo ops and summitry, North Korea wasn’t buying the deal Trump was selling.

As Trump’s whipsaw diplomacy with North Korea draws to a close, the country is no nearer to relinquishing its nuclear arsenal. It has instead blown up a liaison office with South Korea, shot and killed a South Korean man in its waters and last month showcased a new, larger intercontinental ballistic missile in a triumphant military parade.

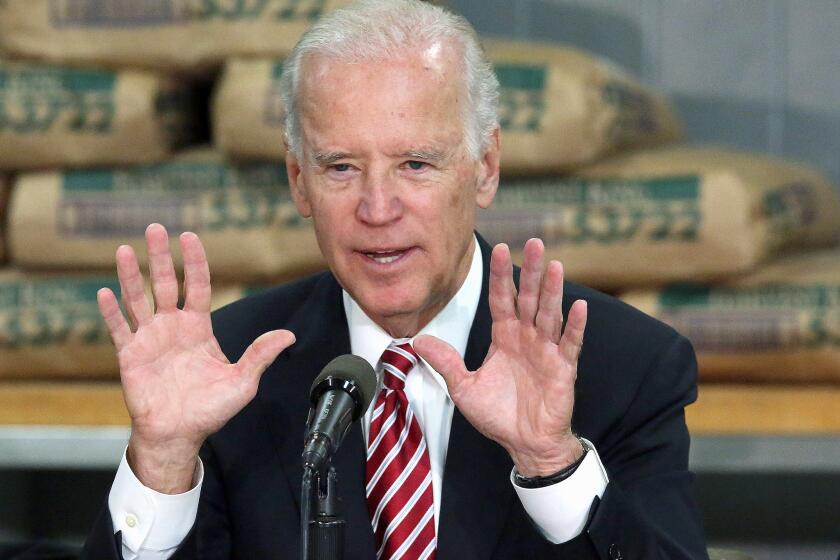

Enter President-elect Joe Biden, who in debates likened Trump’s tete-a-tetes with Kim to meeting with Adolf Hitler on the eve of World War II. The incoming U.S. president has promised South Koreans he will return to “principled diplomacy” in dealing with North Korea and the ever-emboldened Kim.

As capricious and unorthodox as Trump’s approach was, for some on the Korean peninsula, it raised hopes of a breakthrough in the long impasse in talks to denuclearize North Korea. Trump’s engagement with Pyongyang as his foreign-policy centerpiece appeared to jibe with Kim’s eagerness to strengthen his country’s economy and a liberal South Korean president’s desire to improve ties with the North.

Even their outsize personalities and mercurial natures made Trump and Kim well-suited and compelling characters in an odd and fleeting bromance.

“There are South Koreans who would have wanted to see Trump’s unconventional style persist,” said Duyeon Kim, a fellow at Center for a New American Security, a U.S. think tank. “But it’s not black and white; Trump is a mixed bag.”

Biden and South Korean President Moon Jae-in spoke on the phone Thursday, pledging to collaborate closely on the North Korea nuclear issue, according to South Korea’s presidential office. In the days following the U.S. presidential election, all attention in South Korea has been focused on what Biden’s North Korea policy would look like and whether it would be a continuation of the “strategic patience” approach under President Obama.

“To Koreans, ‘strategic patience’ means putting North Korea on the back burner,” Duyeon Kim said. “President Trump, for better or worse, talked about and thought about North Korea a lot. For the first time in U.S. history, North Korea was on the president’s radar, and that’s been difficult in previous administrations.”

South Korean Foreign Minister Kang Kyung-wha, responding to lawmakers’ questions last week, said she believed Biden would try to capitalize on the momentum Trump built in his summits with Kim Jong Un to continue nuclear talks.

“The achievements of the past three years, the agreements and stated will between the heads of state in North, South Korea and the U.S., I don’t think will go back to square one,” she said.

Whether Trump’s North Korea gambit ever moved beyond square one is debatable. Speaking to the president-elect four years ago at the White House, Obama told Trump that North Korea would be the most urgent problem he would face. Less than a month into Trump’s term, North Korea test-fired an intermediate-range ballistic missile into the sea toward Japan.

How will Joe Biden handle the sensitive relationship between superpower rivals China and the U.S.?

In his first year in office, while North Korea was conducting advanced nuclear and ballistic missile tests, Trump called Kim “rocket man” and threatened him with annihilation. Trump then pivoted abruptly and arranged meetings with Kim to undo a crisis of his own making, as the president’s critics charge. While North Korea has since refrained from detonating nuclear weapons or testing ballistic missiles that could threaten the U.S. mainland, Trump’s three meetings with Kim have yielded no concrete pledges or agreements from either side.

Meanwhile, the stalemate has allowed North Korea to continue expanding its nuclear arsenal unchecked, experts say. The U.S. Army has estimated that North Korea has 20 to 60 nuclear weapons and the capacity to produce six each year. And Kim, after his turns in the global spotlight, has gone from a basketball-loving, chain-smoking, eccentric young leader to a statesman who has stood shoulder-to-shoulder with multiple heads of state, including China’s Xi Jinping and Russia’s Vladimir Putin.

Even so, North Korea was likely hoping for another four years of Trump, viewing him as more inclined than Biden to be flexible on easing international economic sanctions, said Andrei Lankov, a North Korea scholar based in Seoul. North Korean state media has called Biden a “rabid dog” that needed to be put down after he referred to Kim as a murderous dictator.

Lankov said that, due to the heightened U.S.-China rivalry, Biden will be navigating a different landscape in his dealings with North Korea than what he experienced as vice president under Obama. Without cooperation from China, which makes up more than 95% of North Korea’s trade volume, sanctions against North Korea are largely meaningless, Lankov said, and China would be motivated to prop up the North Korean regime as a hedge against U.S. influence in the region.

“This confrontation means China needs a buffer zone,” he said. “With American troops in Japan and in South Korea, the significance of North Korea as a strategic buffer, which has always been very high, has increased even further.”

The freewheeling qualities that made Trump a conundrum in foreign policy, Lankov said, may have been what was necessary to reach a breakthrough on the Korean peninsula.

“Donald Trump was an eccentric and unusually narcissistic guy who was just independent or ignorant enough to make a deal that is completely taboo for everybody else,” he said.

Wi Sung-lac, a former South Korean ambassador to Russia who served as the country’s chief nuclear negotiator from 2009 to 2011, said he was concerned the Biden administration would rule out a summit-based approach to North Korea because Trump claimed his meetings with Kim as among his crown achievements.

“They’ll probably revert to traditional diplomacy. But in an ‘anything but Trump’ approach, they may discount everything he’s done,” Wi said. “We should be wary of that as well.”

Biden has said in debates that he would be willing to meet with Kim, but only if it was clear the North Korean leader was “drawing down his nuclear capacity.”

Wi recalled the final years of the Clinton administration. A rash of diplomatic efforts between the U.S., North Korea and South Korea seemed on the verge of reaching a deal. There was even talk of President Clinton visiting Pyongyang to finalize it.

But he ran out of time. Soon came 9/11 and President George W. Bush’s designation of North Korea as part of the “Axis of Evil.”

There was little the government in South Korea could do, Wi recalled. Then and now, he said, “there are no points of agreement, and the clock keeps ticking.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.