‘Montana values’ could decide which party controls the U.S. Senate

HELENA, Montana — Even in a year that has defied prediction, it seems safe to say that President Trump will win Montana.

Much less certain is whether his popularity here will trickle down the ballot and help Republicans maintain control of the U.S. Senate.

Fighting to keep his seat, Republican Steve Daines is locked in a close contest with his Democratic challenger, Gov. Steve Bullock.

It’s by far the most closely watched race in Montana, a state that tilts Republican but prides itself on a spirit of fierce independence — commonly attributed to “Montana values” — that bucks the national tendency to put party loyalty first.

The state hasn’t been without a Democratic senator since 1913 — and only three Republicans have held the office since World War I.

And so it is that the costliest political race in Montana history has become an argument over who is more authentically Montanan.

“We live in the most beautiful state in America, but what makes Montana truly special is the character of our people,” Daines says in a campaign commercial depicting a father-daughter fishing outing.

“Montana is a place where a handshake means something and your word is your bond. As a fifth-generation Montanan, I’m grateful to be passing those values on to my four children.”

Daines, 58, grew up in Bozeman and stayed in town to earn a degree in chemical engineering from Montana State University.

Honoring a standing bet with a friend, he wears a rival University of Montana necktie on the Senate floor when the Grizzlies beat his Bobcats.

After many years at Procter & Gamble, including a stint opening factories in China, he moved back to Bozeman and in 2000 became a vice president at RightNow Technologies.

The tech start-up founded by New Jersey transplant Greg Gianforte sold to Oracle for $1.8 billion in 2012, when Daines left and was elected to the state’s lone U.S. House seat. He won his Senate seat two years later.

When the news organization Roll Call shot a video tour of his Capitol Hill office four years ago, Daines paused at a photograph of a bull elk that he and his son Michael hunted and hefted out to their pickup.

“There’s nothing better tasting than Montana elk,” he explained.

Towns like Whitefish, Mont., once could afford to view the coronavirus as a distant big-city problem. Not anymore.

Not to be outdone, Bullock has played up his own credentials as an outdoorsman.

“Here in Big Sky Country, hunting and fishing is not simply a pastime, it’s our heritage and our way of life,” he wrote on his Facebook page above a photograph of his son Cameron and a buck they bagged. “As a father, there are few things more memorable than taking my son on his first hunt or teaching my daughters how to cast a line in the river.”

Bullock, 54, who grew up in Helena delivering newspapers to the governor’s mansion that he now inhabits, left for Claremont McKenna College in California, majoring in philosophy, politics and economics, and then went on to Columbia Law School.

Upon his return to Helena, he started his own law firm and eventually became attorney general before winning a close race for governor in 2012.

Four years later, even as Trump carried the state by 20 points, Bullock won reelection by defeating Gianforte, painting him as an outsider from back East.

Bullock managed to work with a Republican Legislature to pass campaign finance reform and expand Medicaid to provide health coverage to nearly 90,000 low-income citizens.

His bipartisan credentials were the centerpiece of a brief run last year for the Democratic nomination for president.

As a candidate for the Senate, he has campaigned on the issues of healthcare, education, public lands and support for veterans and seniors.

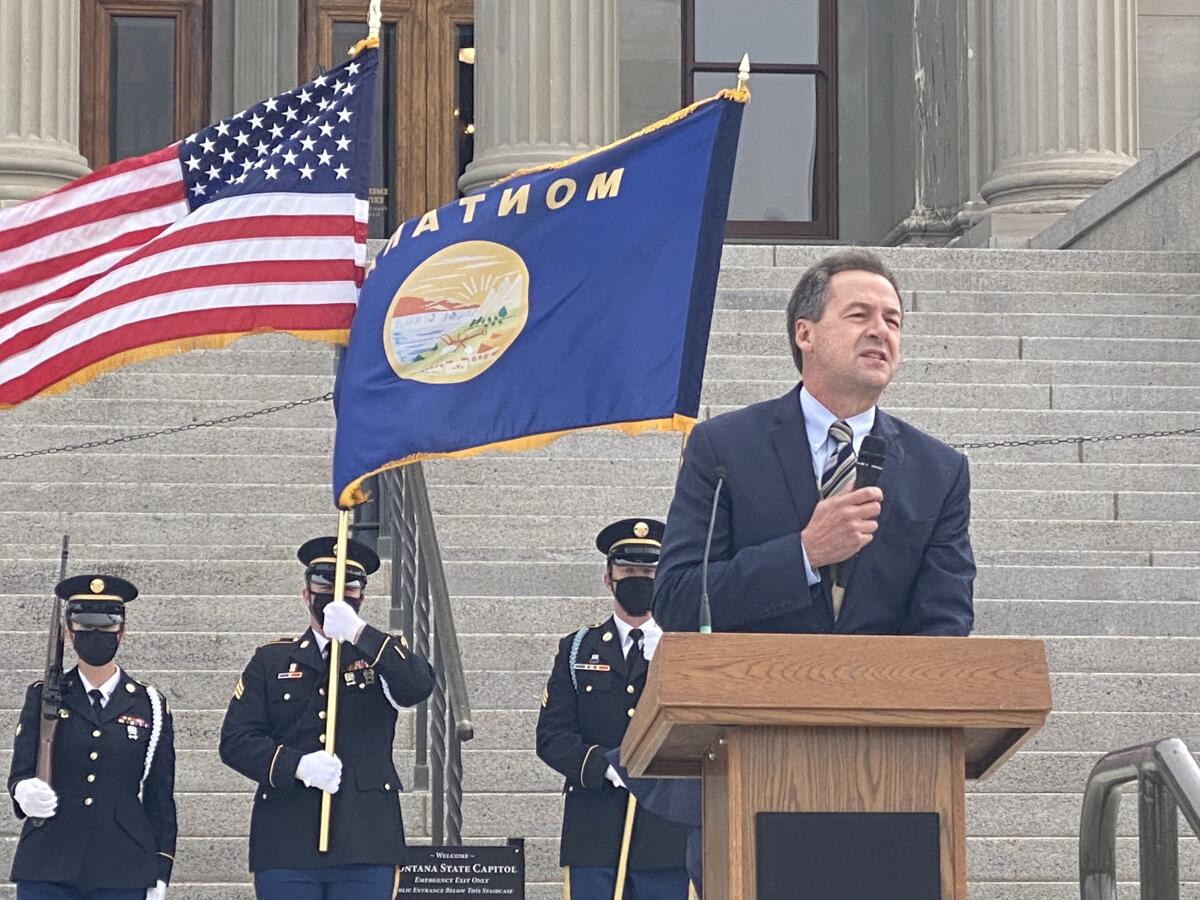

“Those aren’t Democrat or Republican values, those are Montana values!” he yelled from a stage through wind-whipped rain to supporters in their cars at a recent Helena rally that was fashioned after a drive-in movie.

The concept of “Montana values” may sound like meaningless rhetoric, but members of both parties bank on them.

They involve traditional qualities of friendliness, strong communities and a “get ‘er done” mentality, said Brian Kahn, host of Home Ground, an interview show on Yellowstone Public Radio.

“In eastern Montana, they still use the word ‘neighbor’ as a verb, because people in harsh conditions in ranch country can’t make it alone,” he said.

Democrat Jon Tester, the state’s other U.S. senator, said “Montana values” boil down to authenticity, truthfulness and hard work.

“Montana may be different from any other state in the union,” he said. “Montanans pride themselves on split tickets, and on voting for the person.”

Indeed, Montana elects more Democrats than any of the bordering states — deeply red Idaho, Wyoming and both Dakotas.

The state House has 58 Republicans and 42 Democrats but was evenly split between the parties as recently as 2008. Democrats controlled the state Senate as recently as 2006.

In presidential elections, Montana has been reliably Republican for decades with one exception: Bill Clinton won here in 1992, but only because third-party candidate Ross Perot took 26% of the vote.

The race between Daines and Bullock is one of seven rated toss-ups by the Cook Political Report as Democrats try to wrest control of the Senate from Republicans, who currently hold a 53-47 majority.

Daines has closely aligned himself with Trump, who appears to be far less popular than he was in 2016, with polls showing his lead over Joe Biden in single digits.

David Parker, a political science professor at Montana State University, said that while “Donald Trump certainly doesn’t act like a lot of Montanans,” the decline reflects broader concerns about the president’s policies and leadership.

“It’s the fact that his administration in many ways has put the state in jeopardy, through the pandemic, trade wars and the economy,” he said.

The Senate race will come down to people wanting to vote “for someone they know,” he said. “It’s really going to come down to whether independent voters go overwhelmingly for Bullock.”

Daines and Bullock have been a study in contrasts on the campaign trail.

The genial senator has refrained from holding public town halls, instead opting for scripted events with select audiences. The outgoing governor speaks at boisterous, socially distanced rallies.

Money has poured in for both candidates from across the country, with total spending on the race now exceeding $160 million — more than $200 for each registered voter.

Montanans are being deluged by advertising, much of it paid for by outsiders but attacking each candidate as not Montanan enough.

“The Steve Bullock that Montanans elected to governor is not the Steve Bullock who’s running for Senate,” says a radio commercial that warned he would undermine property and gun rights. “He’s lost touch with Montana.”

“Steve Daines went to Washington and forgot all about Montana,” says another commercial. “Daines took over $400,000 from the insurance industry and voted four times to let insurance companies deny health coverage for thousands of Montanans with preexisting conditions.”

Lurking in the background of the race is the coronavirus.

Bullock moved quickly against the pandemic in the beginning, issuing a stay-at-home order that made him look prescient and increased his popularity.

In late April, he began easing restrictions, and with low infection rates and few deaths during the summer, it seemed that the vast, sparsely populated state might skirt the worst of the virus.

But soaring case counts this fall have placed Bullock in a bind, as experts say that imposing new restrictions could cost him votes now that the issue has been politicized.

He says he’s not playing politics, maintaining that county governments need to tailor restrictions to local conditions.

Daines has generally been skeptical of shutdowns, and when Vice President Mike Pence stood with him at a campaign rally last month in Bozeman, neither man wore a mask.

Asked at a recent news conference what he thought Bullock should do, Daines declined to offer any specific ideas or even critique his opponent.

“We need to come together as Montanans to help our neighbors and protect the most vulnerable,” he said. “But we’re a long ways from being out of the woods.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.