In Beirut, one family’s agony is a window to a nation’s suffering

BEIRUT — At 6:06 p.m. Tuesday, Amin Zahed, a 42-year-old father of two who worked as a night manager in the port of Beirut, sent a photograph to his brother on WhatsApp, showing a building at the port on fire.

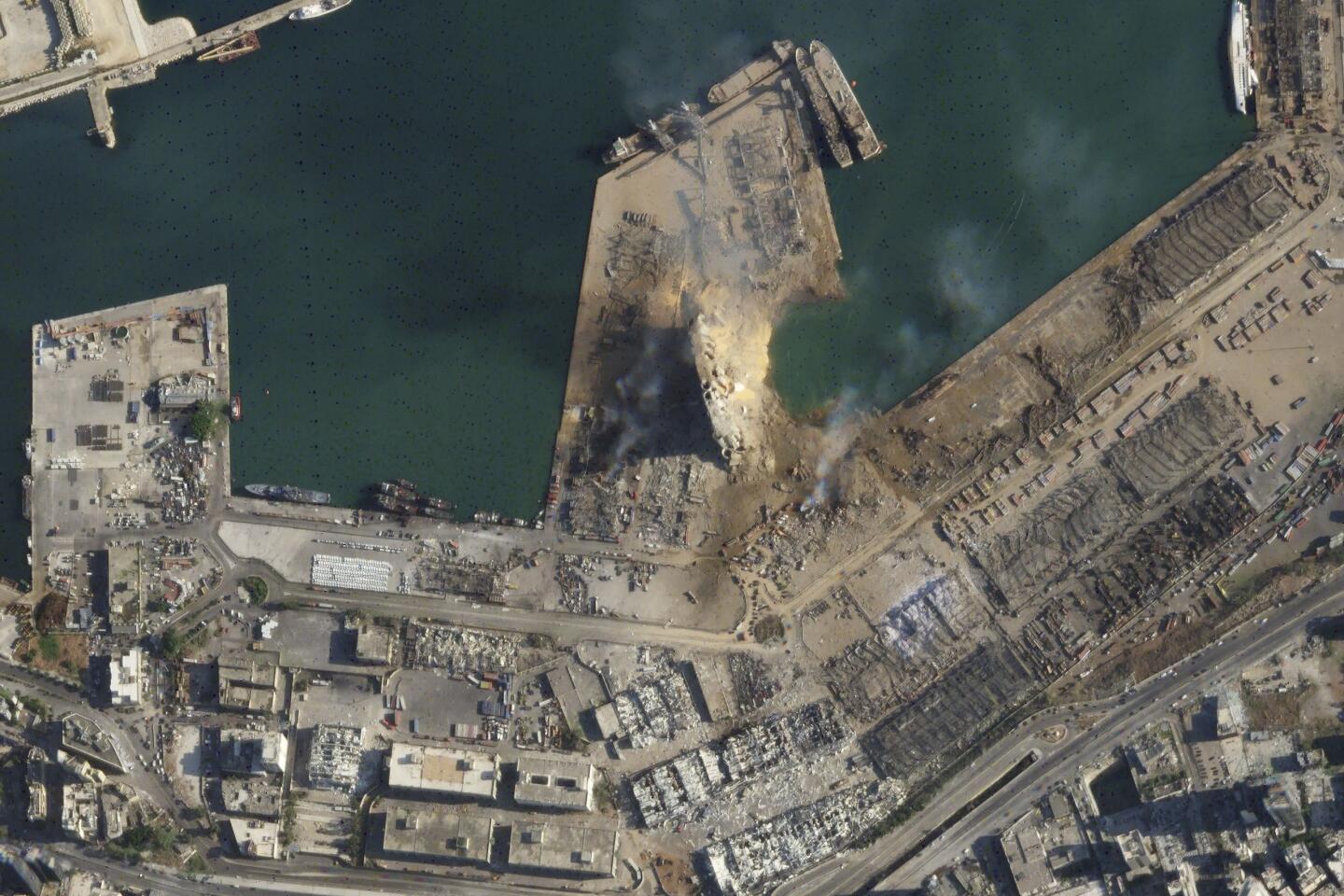

Two minutes later, a massive explosion shook the port, sending up a mushroom cloud that some initially mistook for a nuclear bomb and blasting shock waves across the Lebanese capital.

“He took a picture and sent it to me and wrote, ‘There’s a fire,’” Mohammed Zahed recalled Thursday, standing in front of the port where his brother was last seen. “And then the explosion happened, and he disappeared. He stopped answering.”

Zahed’s wife and siblings immediately began calling anyone they could think of who might have information about his fate. They called the civil defense and the Red Cross. They began a tour of Beirut’s hospitals, which were in a state of chaos, overwhelmed by the wounded. Some of the hospitals had been damaged in the blast. They came up empty.

“For three days, we’ve been going around in circles and searching for him, and we haven’t found him,” said Zahed’s sister, Rima.

The Zahed family is not alone. Tuesday’s explosion — believed to have been caused by a fire that spread to a warehouse storing ammonium nitrate — killed 137 people and injured about 5,000, according to government figures updated Thursday. It reduced buildings that had survived years of war into hollowed-out shells and displaced as many as 300,000 people.

The anger around the tragedy was palpable when French President Emmanuel Macron — who at one point during his tour of the city Thursday — was surrounded by residents angry with their own government chanting “Revolution!”

Estimates of the number of people missing have ranged from the dozens to hundreds. Representatives of the Lebanese Red Cross and Lebanese army said they could not provide an official count.

“There is no precise data because you know it’s a huge” incident, said Red Cross spokesman Ayad Monzer.

Reda Moussawi, advisor to Health Minister Hamad Hassan, said the Health Ministry had a list of about 40 people reported missing and 21 unidentified bodies were in various hospitals.

Lebanon’s Disaster Risk Management unit announced Thursday that it had set up a hotline for family members to report or request information on missing loved ones. In the meantime, many families had already resorted to searching on social media. An Instagram page set up to help families find missing loved ones has garnered more than 108,000 followers.

It was also via social media that the Zahed family received the news that at first seemed to mean its search was over.

On Wednesday, photographs and video being circulated showed a boat carrying a group of wounded men who had been pulled from the sea by an army rescue team.

“There’s a boat with six people in it, and one of them is my brother,” Rima Zahed said.

“His face was clear” although he was bloodied, she said. “We knew it was him, that my brother is alive, he is moving.”

News sites began to pick up the story from social media and declared it a miracle: The missing port worker had been pulled from the sea after 30 hours. (In reality, Mohammed Zahed said, his brother was probably in the water only for about an hour.)

The family managed to get in contact with a member of the rescue team, Mohammed Zahed said, but there they hit another blank wall.

“He told us, ‘I rescued him and he was still alive, he was breathing, and they took him out and brought him to the military hospital and from the military hospital, the Red Cross took him,’” Mohammed Zahed said, noting that his brother could not be admitted to the military hospital because he is not a member of the army.

But neither the army nor the Red Cross could tell them which hospital he had been taken to after that, he said.

A Red Cross spokesman referred questions about the case to the army. An army spokesman did not respond to a request for comment.

Once again, the family began making the rounds of the hospitals, but the answer was always the same: They had no patient by the name of Amin Zahed.

Zahed’s 9-year-old son, the younger of his two children, still doesn’t know that his father is missing, Rima Zahed said. He believes his father has been at work for the last three days.

Rima Zahed is certain that her brother is alive and will come home again. Pulling up the video of the rescue on her phone, she points to the image of him lying on the bottom of a small fishing vessel.

“Look at my brother — my brother didn’t die, this is him, look. This is my brother, sleeping on the floor, my brother is alive, he’s breathing.”

But she’s beginning to lose hope of finding him.

“It’s not one or two or three or four — we’ve searched all of the hospitals in Lebanon,” she said.

While they are frustrated with the Kafkaesque nature of the search, Mohammed and Rima Zahed save most of their vitriol for the government officials whom they hold responsible for the explosion.

The warehouse that caught fire held about 2,750 tons of ammonium nitrate that had been stored there for years after being confiscated from a cargo ship by Lebanese authorities, despite warnings that it could pose a hazard to Beirut’s residents.

The government has launched an investigation and placed port officials under house arrest. A military judge leading the investigation said that 16 port employees had been detained and 18 questioned, including port and customs officials.

But many Lebanese, who had already been enraged by the government’s inertia in addressing the country’s economic crisis, saw the actions as a deflection of responsibility. Soon after Macron toured Gemmayzeh, one of the areas hardest hit by the blast, Justice Minister Marie-Claude Najm tried to visit the area but was driven out by protesters shouting, “Resign, you criminal!”

The Lebanese are used to eating plenty of meat, but the country’s economic woes have made it a luxury as rampant inflation takes its toll.

Macron also alluded to the government’s crisis of confidence in his remarks. While announcing that France will organize a conference in the next few days to raise funds from international donors for the humanitarian response, he warned that he would not give “blank checks to a system that no longer has the trust of its people” and called on the Lebanese to create a “new political order.”

The Zahed family members, like many victims of the blast, are bitter toward the government they see as responsible for their misfortune.

“To the government: May God not give you good fortune,” Mohammed Zahed said. “May God not give you good fortune, all of you.…This is a government of liars and con men.”

While the Zaheds were standing in front of the port, a journalist approached Rima Zahed and told her he had gotten a tip that her brother was at the American University of Beirut hospital, but it turned out, once again, to be a false lead. The family continued its rounds.

Sewell is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.