PORTLAND, Ore. — Participants in the “Wall of Vets” mustered early, setting up a human chain at nightfall in front of the Mark O. Hatfield United States Courthouse.

“I’m a middle-aged white guy. I’ve got a house, two kids, a dog,” said Adam Simmons, 43, a former Army medic in Iraq. “I really don’t need to be here.”

But there he was, along with a dozen or so other veterans — both white and Black — to bear witness and protect demonstrators’ right to protest.

Often called the “whitest” U.S. big city — more than 70% of the population is non-Latino white — Portland has transformed into a national center for a movement that might seem more at home in Chicago, New York, Los Angeles or another more diverse locale. “Black lives matter” has become a ubiquitous rallying cry in a city where only about 6% of the population is Black — while almost 10% is Latino and 8% is of Asian ancestry.

The city of 650,000, a 90-minute drive from snow-capped Mt. Hood, has long had a reputation as an easygoing town with efficient public transportation, mild weather, good public schools and progressive politics. It’s an urban space for people who love the outdoors. Oregon was a leader in the decriminalization of marijuana.

Racial discord seems a distant concern in a state whose history is caught up in the lore of Lewis and Clark, the Oregon Trail and 19th century stagecoaches delivering intrepid pioneers.

But many say the idealized image blots out an ugly legacy of intolerance and antipathy toward Black people, and ignores serious problems such as homelessness and drug use.

A key reason why Portland is overwhelmingly white is that Black people were excluded from residing in Oregon until well into the 20th century, said Ethan Johnson, associate professor and chair of Portland State University’s Black Studies Department.

Though Oregon experienced an influx of Black workers during World War II, it was the Pacific state that received the fewest number of Black transplants during the 20th century’s Great Migration from the South, Johnson noted.

That was in part because it was viewed as particularly unwelcome to Black people.

“While this is a progressive city, the other side of the coin is that there is a hidden picture of Black people who are suffering,” Johnson said, citing high rates of high school dropouts, homicides, incarceration and poverty among Black residents.

Gentrification, urban renewal, flooding and other factors have dispersed a Black population that was small to begin with. Portland no longer has a distinctive Black neighborhood.

It is, at the same time, a city with a tradition of social movements and activism, including protests in 2003 against the Iraq war, the 2011 Occupy Portland rallies inspired by the Occupy Wall Street movement, and frequent mobilizations focusing on police violence.

“There’s a lot of activism and institutionalization of resistance and support here for people who feel deeply marginalized here, both Black and white,” Johnson said. “There is a consciousness here about inequality … a culture that ‘if you’re violating my civil rights, then I’m going to speak up and protest.’”

To this day, some Black residents speak of a kind of subtle racism, a sense of condescension.

“People in the South tell you to your face that you don’t belong here,” said Anita Randolph, a Black neuroscientist at Oregon Health and Science University who previously resided in Atlanta, a majority Black city. “But in Portland it’s not like that. It’s manipulative. … There’s a white savior attitude.”

For some Black protesters, that posture has somewhat dimmed the protest experience.

“I guess I’m not completely happy that white people have to protest so that my concerns get addressed,” said Jay, 19, a Black woman who said she had participated in 50 nights of protests but did not want her surname used so as not to alienate white colleagues.

A native of Mississippi, Jay said she had never been called the N-word until she moved to Portland two years ago. “They don’t have the gun racks and Confederate flags here, but there’s still racism,” she said.

But other Black people interviewed said they have been heartened, even moved, by the outpouring of support from many white people.

“There’s a lot of free-thinking people here — and that’s a good thing,” said Vaughn Waddell, 49, a Black native of Brooklyn, N.Y., who sells Black Lives Matter T-shirts from a street stand — one of the few thriving concerns in a ghostly downtown where many business owners have shut down and nailed plywood on shop windows to avoid potential vandalism.

“People here don’t have the old hang-ups,” Waddell added.

He then pointed to a young white woman who had stopped to look at his T-shirt selection. “Ask her.”

She is Grace Kyle, 20, and she praises Black Lives Matter.

“It’s a civil liberties issue for everyone,” Kyle said. “If racism is not stopped, it could affect everyone.”

She purchased a $20 Black Lives Matter T-shirt from the stand.

White protesters, many of them young, have become foot soldiers in the racial justice movement here focusing on the federal courthouse.

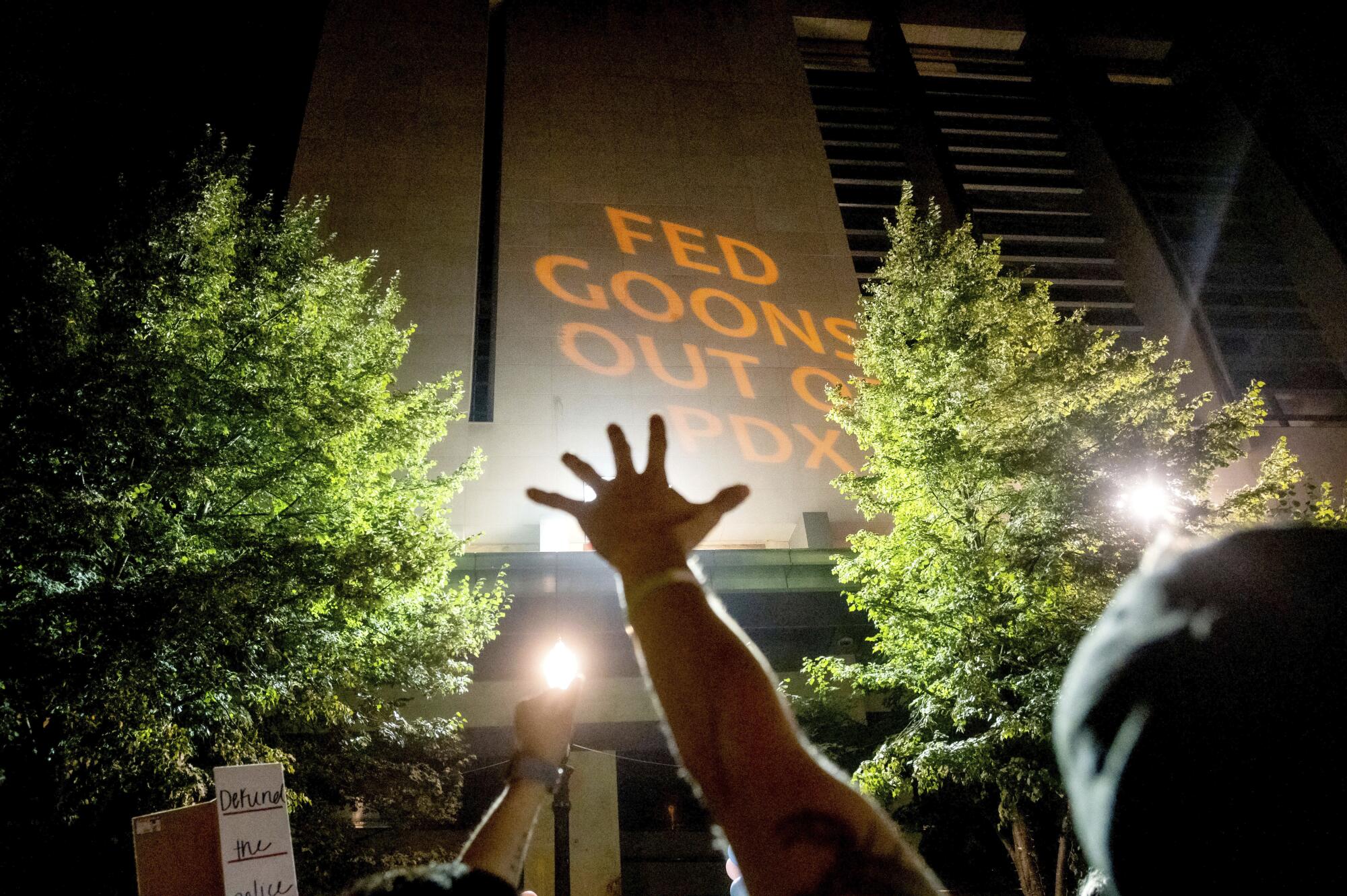

The courthouse is a graffiti-glazed Fort Apache, set off by concrete blast barriers and a metal fence; its lower-level windows are boarded up, and, in the evenings, a bank of high-powered lights shine down on the crowds assembled below. Conflicts outside have waned since authorities agreed last month to remove heavily armed federal agents. But nightly protests continue.

Among the protesters on a recent evening was Josie Chole, 19, who bore a handwritten sign declaring, “If you’re tired of hearing about racism, imagine how tired people are of experiencing it.”

Chole, a recent transplant from Arizona who is white, objects when people tell her that “all lives matter.”

“They don’t get it,” she said on a recent evening as she stood on a corner across from the courthouse. “This is the moment for Black Lives Matter. That’s all that matters.”

Protesters have directed their ire not only at the federal courthouse, which became a proxy for President Trump after he ignored local public officials and ordered deployment of the camouflage-clad federal agents, who routinely fired tear gas canisters and other projectiles at protesters. Earlier, demonstrators targeted a seemingly benign statue of a stately elk that stood in a downtown park for more than 100 years. The sculpture went from being a source of civic pride to a symbol of colonialism and dispossession.

“Stolen land!” was one of the protesters’ chants, referring to territory taken from the region’s original Indigenous inhabitants. “Give it back!”

Authorities removed the statue last month after its base was damaged during the protests. Some criticized the demonstrators online, wondering if the elk had exhibited signs of racism or white supremacy.

Many residents here complain that the national focus on the protests has distorted the image of the city, playing into Trump’s hand of declaring it a hotbed of “anarchists and agitators” from the anti-fascist movement known as antifa, which in actuality has no central organization or membership roll.

“If you go two blocks away, things are relatively normal,” said Robert Atkinson, 77, a retired lawyer who held a sign declaring “Feds Go Home” as he stood in front of the courthouse. “Unfortunately, the media concentrates on the violence, but those involved in violence are only a small minority.”

There is no doubt that some protesters have looked for trouble, tossing fireworks, bottles and rocks at the courthouse complex. But most protesters deny trying to foment chaos, saying they have been defending themselves against overzealous federal officers dispatched by Trump.

“This is not just random violence,” said Wolfgang Taylor, 19, who brandished a particle-board shield — bearing a hole where it was hit by a tear gas canister fired by guards at the courthouse.

“We have legitimate demands,” Taylor said. “We want to professionalize the police. There should be psychological assessments for those with repeated complaints against them.”

He then put on his gas mask anew and lunged back into the bedlam at the courthouse, shield out front. Other allies used leaf blowers to disperse the gas.

Despite Portland’s progressive image, not everyone supports the nightly spectacle. On a recent afternoon, many motorists flashed thumbs-up signals to police who were clearing a homeless encampment from a park directly in front of the courthouse.

Across the street, a group of counter-demonstrators held up signs declaring, “Support the Police,” and cheered every time officers passed by with arrested protesters in custody.

“Everyone wants to be a victim now,” said Shelly Fenner, 51, a pro-police demonstrator. “I think a lot of them are indoctrinated, politically and educationally. They want us to feel guilty about something that happened to Black people’s ancestors. That’s not our fault.”

As she spoke, two police officers walked by with a handcuffed young white woman who wore a Black Lives Matter halter top.

“Jesus doesn’t love you!” the arrestee yelled at the pro-police activists.

Protesters say they plan to continue their nightly demonstrations outside the courthouse. Before nightfall, a carnival atmosphere dominates, as speakers exhort the crowd, some of those gathered prepare signs and volunteers dispense free food, water and masks.

“I don’t think Portland has had a moment like this before,” said Damien Fair, 44, a Black health professional who lived in Portland for 12 years before returning last month to his native Minnesota. “This is something different. My only hope is that it makes for real change.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.