Pilgrimage ‘by proxy’: Coronavirus spurs new technologies for age-old hajj

BEIRUT — In the best of times, it’s hard to land one of the slots Saudi Arabia parcels out for the hajj, the annual pilgrimage to Mecca that all Muslims are duty-bound to make at least once in their lives. In the worst of times — cue the coronavirus — it’s well-nigh impossible, with the numbers for this year’s event, now underway, capped at just 1,000.

But in these most technologically advanced of times, what if Mecca could be brought to you? That’s what some app developers are trying to achieve, in hopes of giving worshipers a virtual way to experience the holy rites of Islam that the COVID-19 pandemic, or more common impediments such as age and poverty, has denied them this summer.

“People save money their whole lives to do this pilgrimage, and we don’t want to be considered as a substitute,” says Adnan Maqbool, project director for the British-based company Labbaik VR, which has created a virtual-reality simulation of the hajj and the umrah, a shorter, optional version of the hajj.

“But what we do want is for people to at least feel what they’re missing out on — and during these times it’s the most important thing to have.”

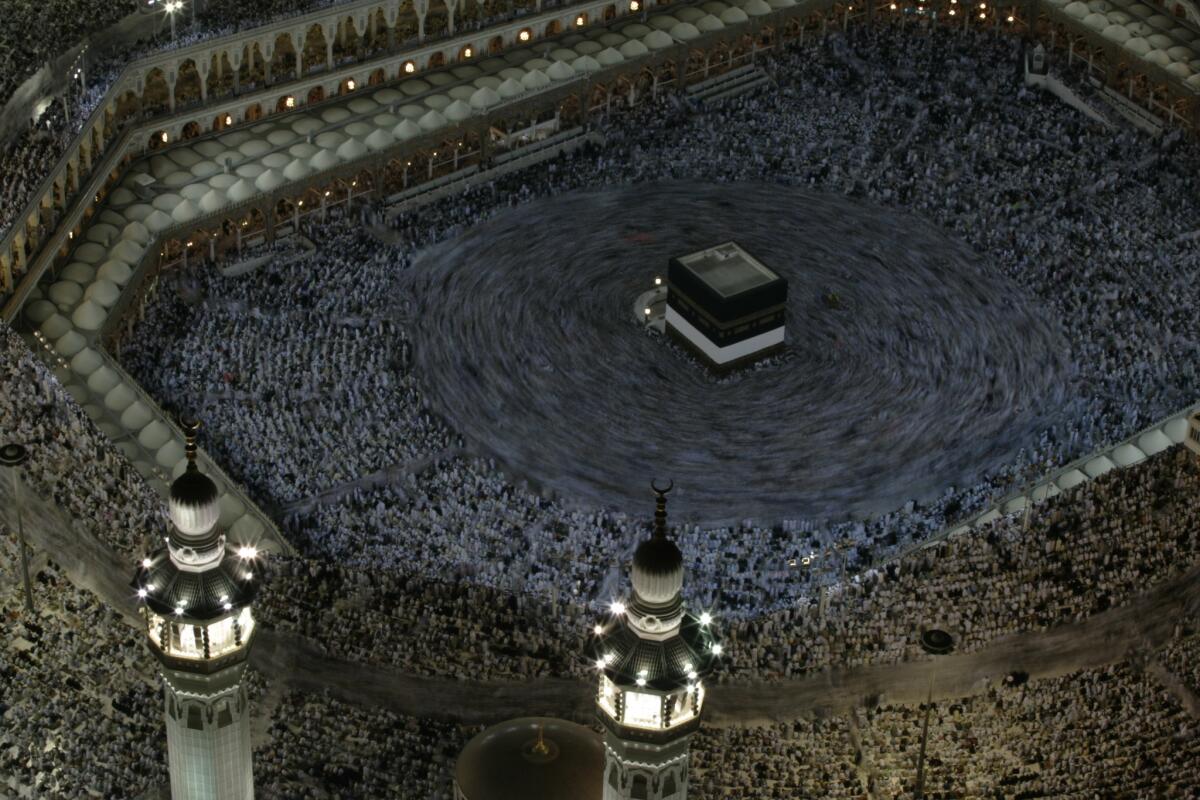

To achieve that the Labbaik VR technology, which took eight years to make, uses tens of thousands of high-resolution images that are then painstakingly placed on a detailed 3-D model of Mecca. People experience the site using virtual-reality headsets such as the Oculus Rift. They can walk around the Kaaba, the black stone structure that is Islam’s holiest shrine, among pilgrims dressed in the simple, terry-cloth clothing traditionally used for the pilgrimage.

“We’re normally very distracted — that’s just part of life these days with smartphones. But once you put on the headset, you’re completely removed from everything else. That’s critical to feeling anything of a spiritual nature,” says Shehriar Ashraf, Labbaik VR’s chief executive.

“We’ve also re-created Mecca in the time of Abraham. It’s fascinating, and we’ve done it exactly to scale from historical records,” Ashraf adds.

Muslim pilgrims in face masks have begun arriving at Islam’s holiest site in Mecca for a very different hajj amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

The company has offered its product as a tool for prospective pilgrims to train for the various stages of the hajj, a sort of dry run before they experience the real thing.

But because of this year’s lockdowns, not to mention supply chains of headsets disrupted by COVID-19, training pilgrims lucky enough to go to Mecca was less of a priority, Ashraf says. The company instead pivoted to Wuzu, a free mobile phone app that also re-creates the hajj and umrah experience.

“We aim to combine it with duaa [prayers], dhikr [repeated utterances of ‘Allah’] and a virtual walk-through,” he says.

Another hajj rehearsal tool finding new relevance is Muslim 3D, an edutainment video game developed by the German company Bigitec. The demo version of the app, according to Bigitec’s managing director Bilal Chbib, has been downloaded half a million times, 60% of them in the last three or four months.

In the app, users control a 3-D avatar, exploring the history behind important Islamic figures. They can also interact with characters in a game-like setting and learn how various Islamic rites came to be.

“Using this technology is a huge opportunity to make it very immersive,” Chbib says. “You can become a witness to those events.”

Over 2 million Muslims from around the world are beginning the five-day hajj pilgrimage Sunday.

The genesis for Chbib’s project came almost a decade ago, when he saw that most video games featured Muslim characters as cannon fodder or, at best, villains. A professional game developer himself, he wanted to create something that would combine his love of the medium with his own background.

“Corona has accelerated things, but we’re exploring how we can offer a solution, how to play a role,” he says. “There’s a necessity to create something like this … I don’t think this virus is leaving us so easily.”

The coronavirus’ effects have been acutely felt by Muslims worldwide this week, both in the hajj, which began earlier Wednesday and concludes on Sunday, and in Eid al-Adha, the “Feast of Sacrifice,” which accompanies the final days of the pilgrimage and which began Friday.

In pre-coronavirus times, the feast would be a happy occasion, with families engaged in daylong visits, slaughtering sheep and distributing gifts before they receive pilgrims returning from the hajj.

Instead, it was a somber moment in the Lebanese capital Beirut, where a renewed lockdown — not to mention an economic crisis only worsened by the contagion — kept thoroughfares empty and celebrations subdued. The scene was repeated in other Muslim nations, such as Iraq.

But the effect on the hajj was even more drastic, with the Saudi government imposing extraordinary measures aimed at preventing any chance of infection. Collectively, they made for a surreal iteration of one of the most important events on the Muslim calendar.

Although all 1,000 participants allowed this year are permanent or temporary residents of Saudi Arabia, they had to quarantine at home for a week before arriving in Mecca, where they underwent a further four days of isolation.

At the pilgrimage site, the usual crush of people making their way around was replaced with buses making staggered departures to reduce crowding. Medical personnel conducted regular spot checks, with pilgrims given care packages containing masks, antibacterial wipes and sanitizers. The tawaf — or circumambulation — of the Kaaba saw worshipers solemnly walk along color-coded lines, wielding matching parasols to shield themselves from the sun.

Technology played a part in safety as well, foreshadowing what may soon become permanent features of the pilgrimage. Authorities used tracking bracelets linked to a smartphone app, while giving pilgrims a “smart card” loaded with their personal information and a bar code to regulate movement. Saudi Arabia’s Ministry of Islamic Affairs said it debuted a robot connecting pilgrims to scholars through video-conferencing for religious counseling.

News Alerts

Get breaking news, investigations, analysis and more signature journalism from the Los Angeles Times in your inbox.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

A similar drive to incorporate technology into the ritual pushed Kenyan entrepreneur Ahmed Haddad to create iUmrah.World, a platform connecting worshipers to people in Saudi Arabia willing to do the “little pilgrimage” on their behalf. The umrah was canceled by Saudi Arabia in February because of the coronavirus.

Even without COVID-19 restrictions, Haddad says, many Muslims won’t have the chance to visit Mecca, whether because of age, expense — a trip can cost well above $3,000 — or the sheer amount of time required for one’s turn to come. Although the Saudi government has increased the capacity of shrine areas to accommodate ever greater numbers of pilgrims — 12.5 million people performed either the hajj or umrah last year — it still imposes quotas on how many pilgrims any country can send. In Indonesia, the world’s most populous Muslim nation, the wait can take 20 years or more.

“Before the corona era, people didn’t pay much attention to it. They’re now much more willing to accept hajj and umrah by proxy,” says Haddad of his start-up, which he founded in 2015. He added that the company was now waiting for the rollout of 5G technology to launch iHajj, which would follow a similar model to iUmrah.World but allow for continuous streaming for the five days of rituals.

Ashraf, Labbaik VR’s chief, hopes his product can lead to greater understanding between different religions by giving virtual access to non-Muslims, who are barred from visiting Mecca.

“When we exhibited in Dubai last year, we had a lot of interest from non-Muslims, who seemed really excited,” he said. “We got a phenomenal response. Honestly, we didn’t expect it.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.