Eulogized by presidents and civil rights leaders, John Lewis laid to rest in Atlanta

ATLANTA — John Lewis, an icon of Congress and the civil rights movement, was laid to rest Thursday in Atlanta, eulogized by former presidents and civil rights leaders who celebrated his commitment to justice and urged Americans to carry on his mission.

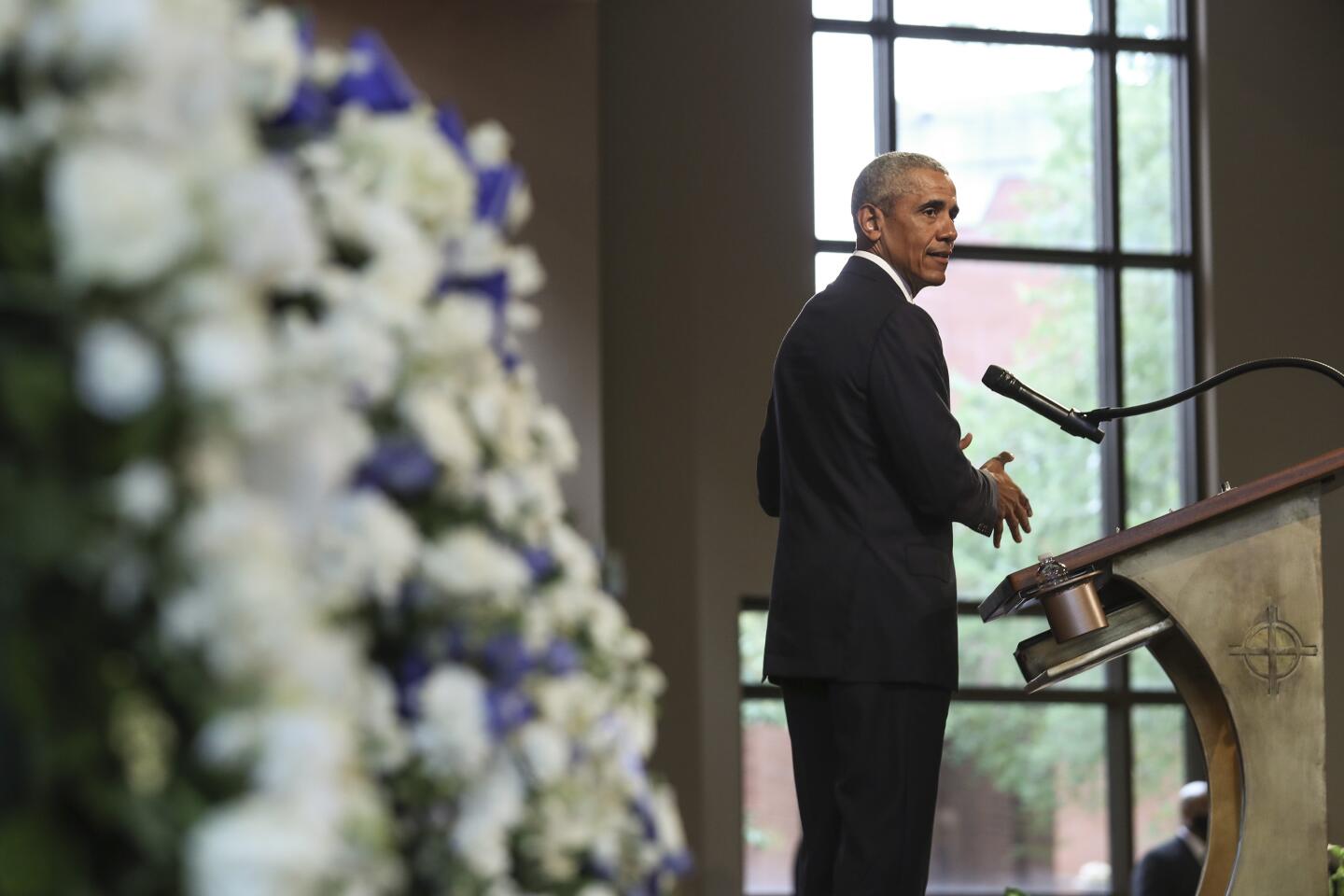

Speaking from the pulpit of Atlanta’s Ebenezer Baptist Church, former President Obama said he owed a great debt to Lewis, whom he hailed as a “man of pure joy and unbreakable perseverance” and “a founding father of that fuller, fairer, better America.”

After praising Lewis’ courage as a young Freedom Rider who led sit-ins against segregation and marches for voting rights to “challenge an entire infrastructure of oppression,” the nation’s first Black president stressed that Lewis’ work was not done.

“He knew that the march is not yet over, that the race is not yet won, that we have not yet reached that blessed destination where we are judged by the content of our character,” Obama said.

In a pointed critique of Republicans, Obama condemned those who are “doing their darnedest to discourage people from voting” by closing polling stations, targeting minorities and undermining the Postal Service ahead of the November general election. He also weighed in on the Senate filibuster, the tool that has allowed a minority of senators to block voting rights measures and other legislation.

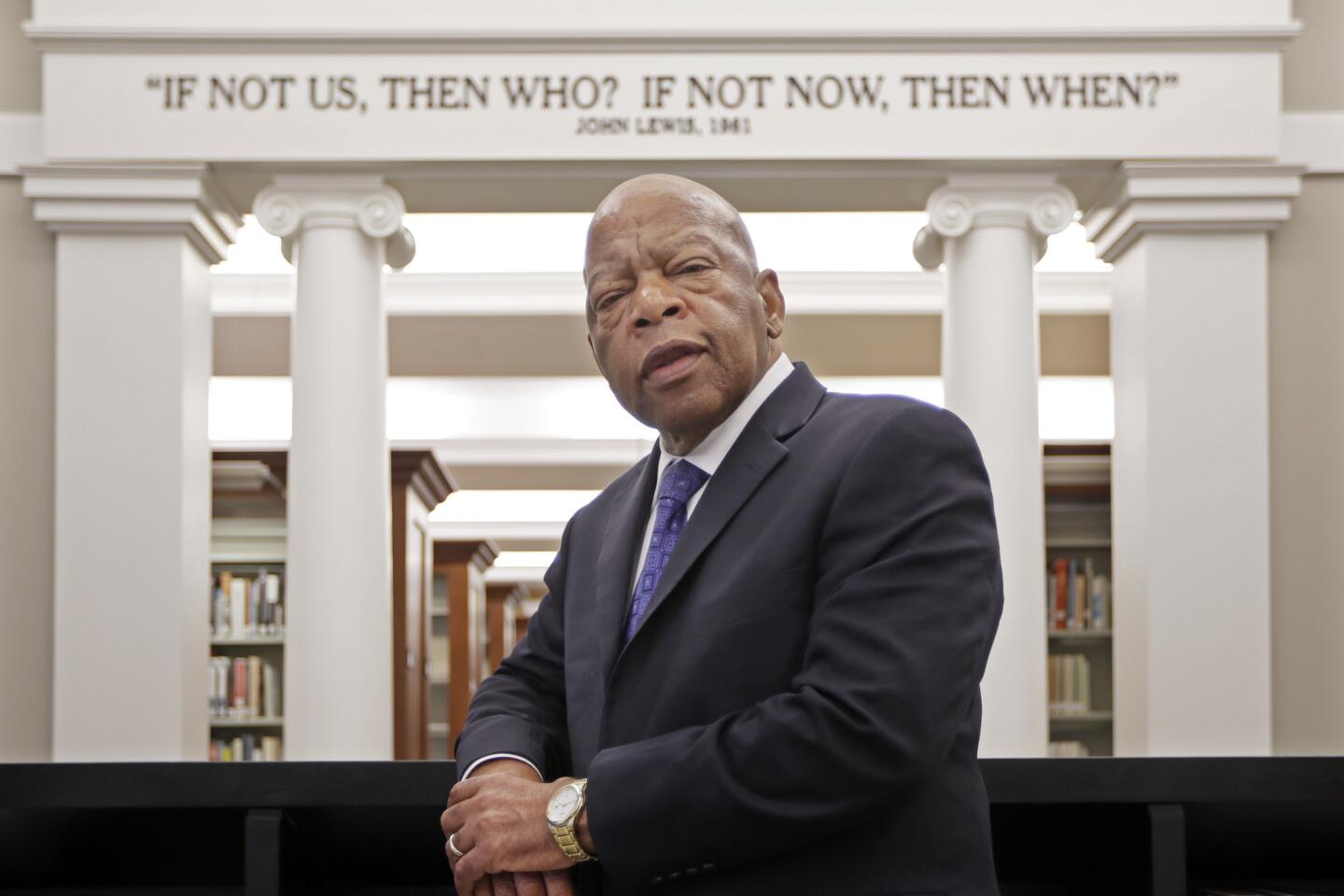

“Once we pass the John Lewis Voting Rights Act, we should keep marching,” Obama said. “And if all this takes eliminating the filibuster — another Jim Crow relic — in order to secure the God-given rights of every American, then that’s what we should do.”

Joe Biden is expected to be among those honoring the Georgia lawmaker and civil rights icon at the Capitol.

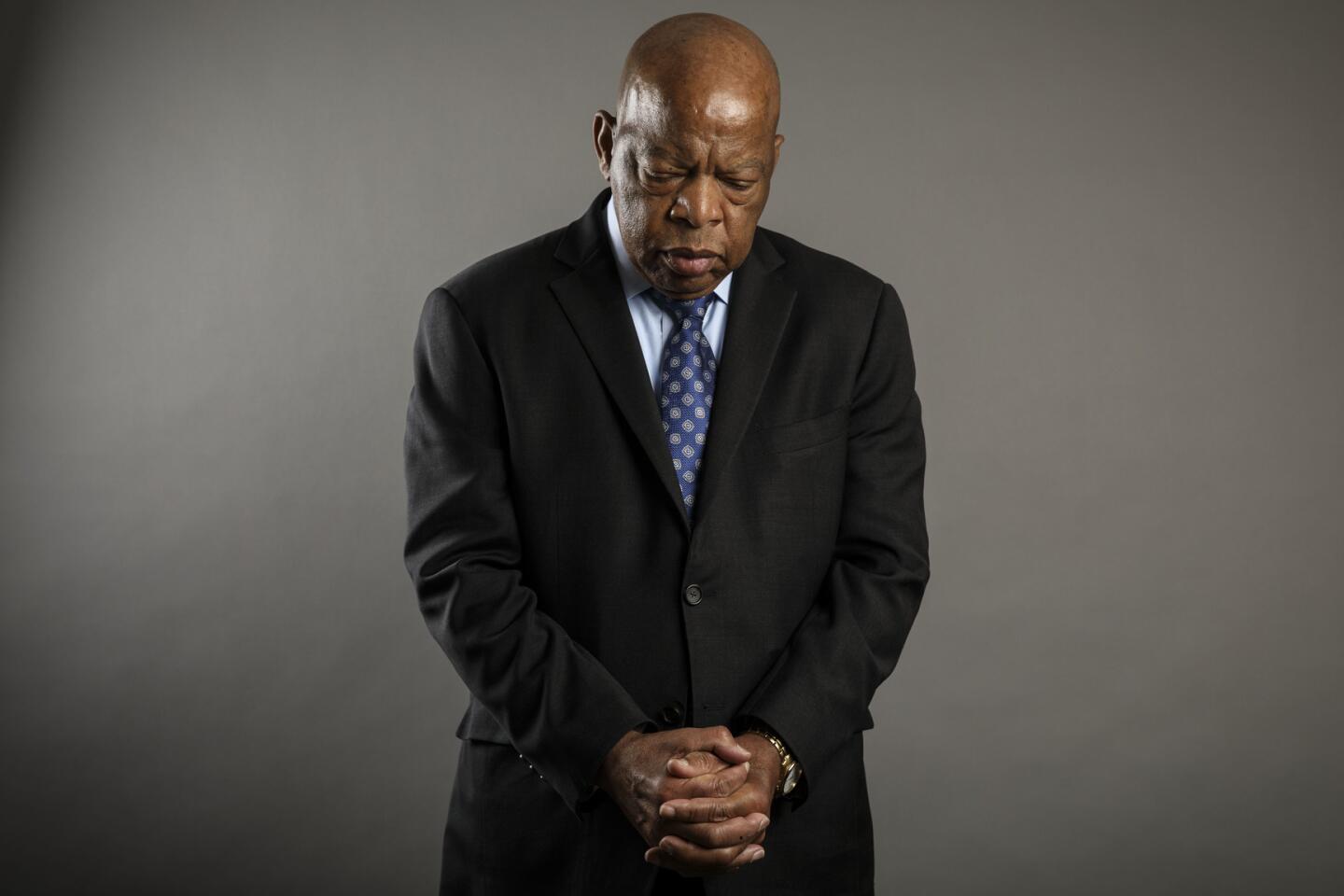

Lewis, who played a pivotal role in the struggle for voting rights in the Deep South, died July 17 at the age of 80, seven months after he was diagnosed with Stage 4 pancreatic cancer.

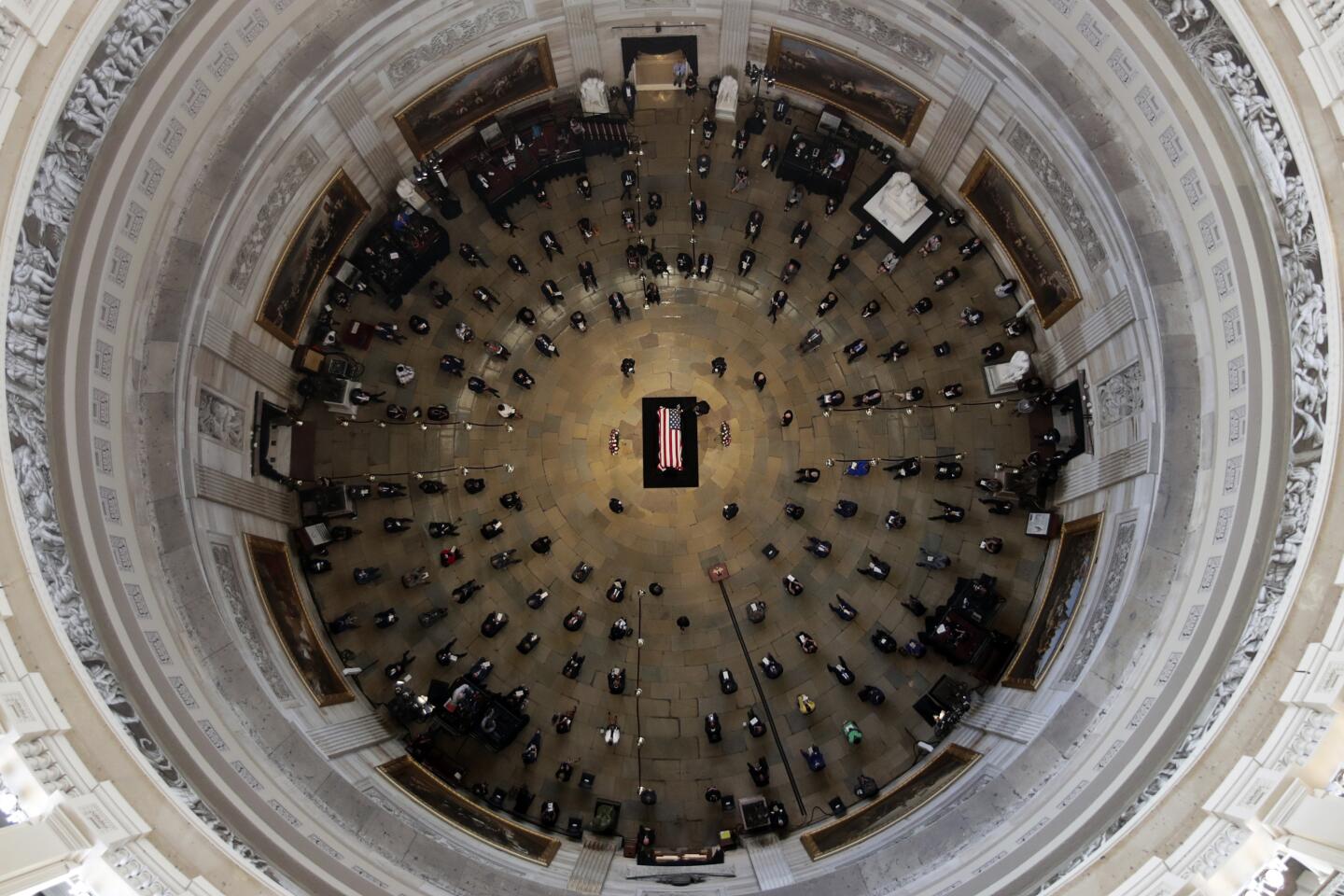

He has been mourned for nearly a week — from his birthplace of Troy, Ala., to the nation’s Capitol, where he represented Georgia for more than three decades.

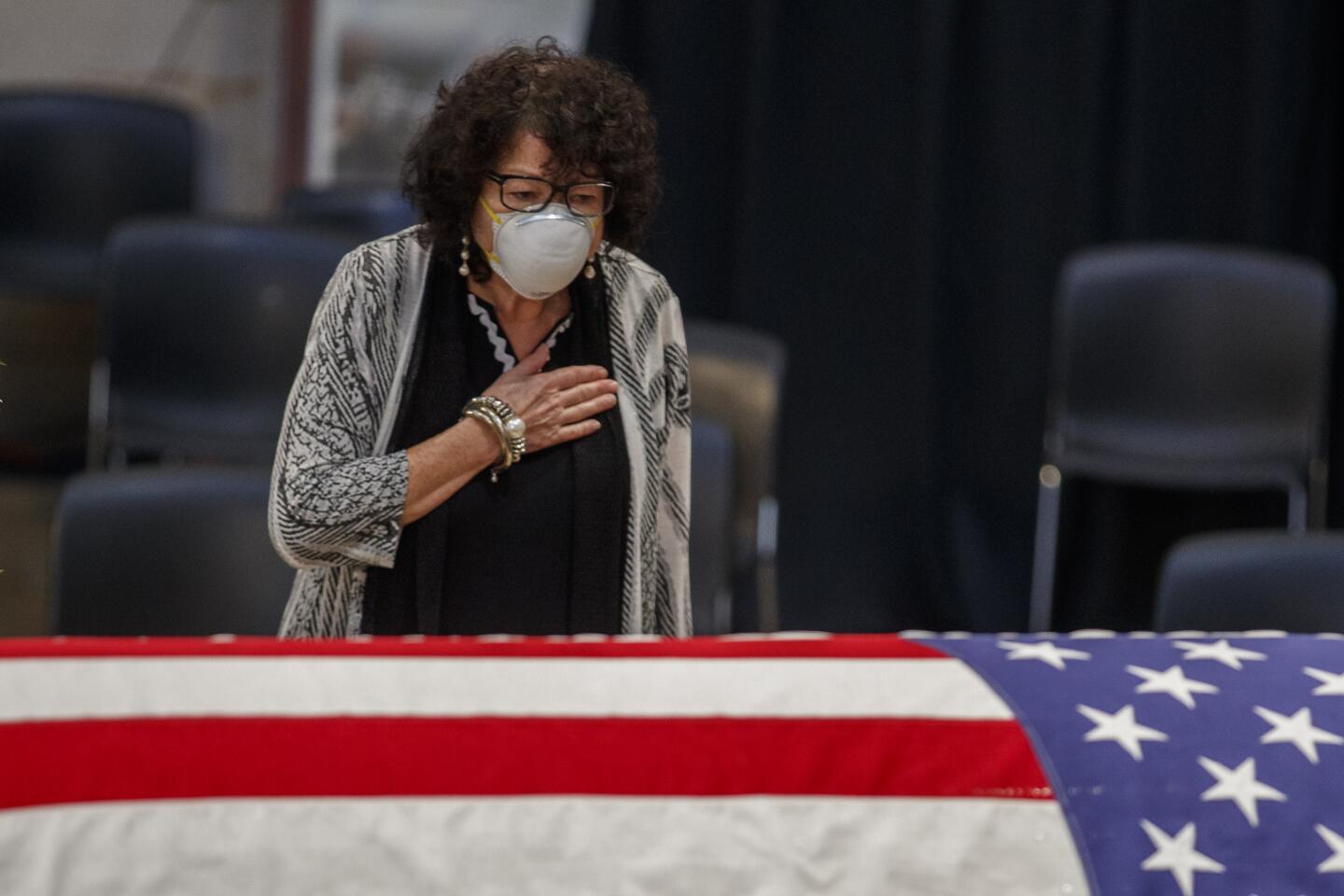

Lewis’ casket, draped in a United States flag, was carried Thursday into the church where he had been a member since the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. was co-pastor.

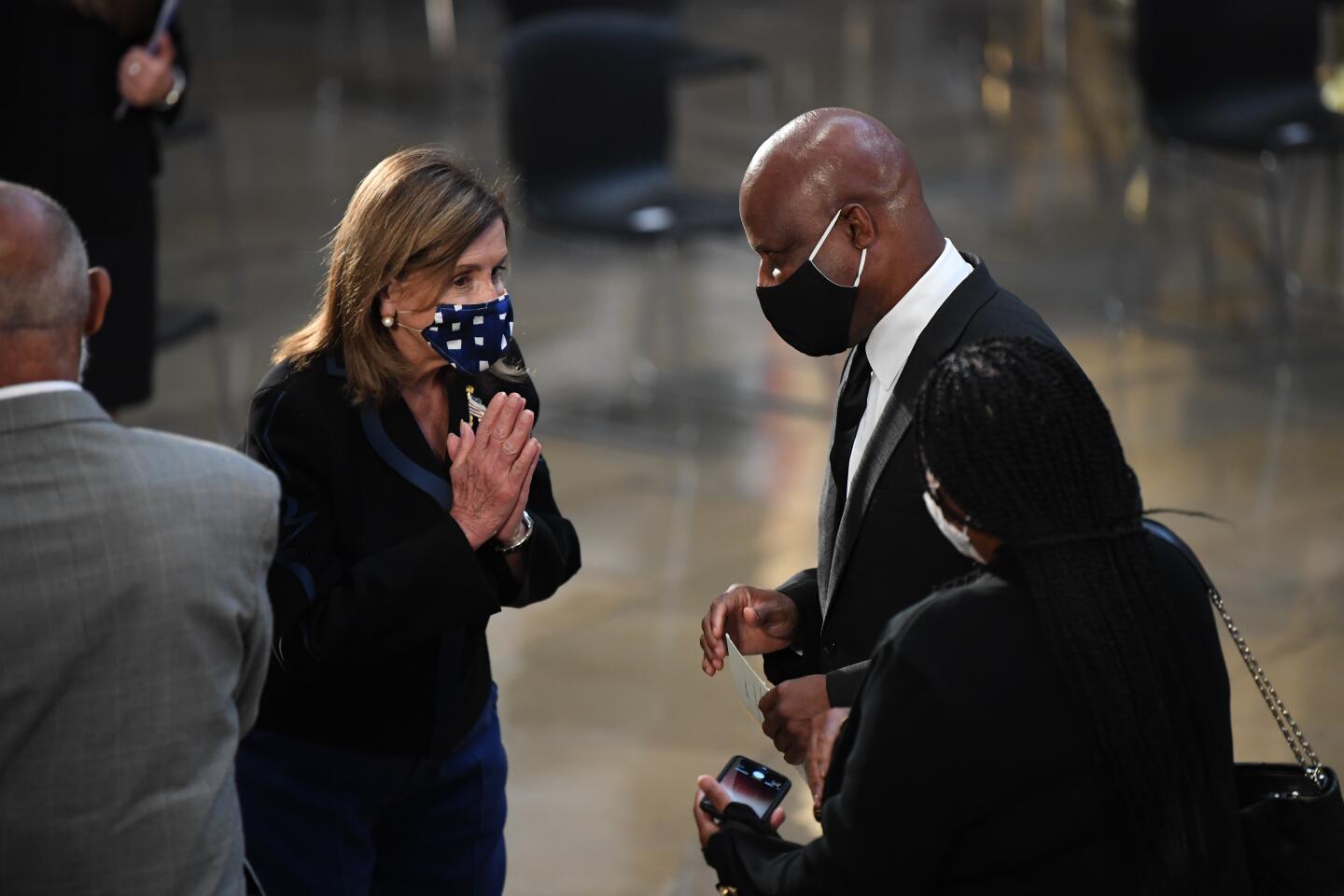

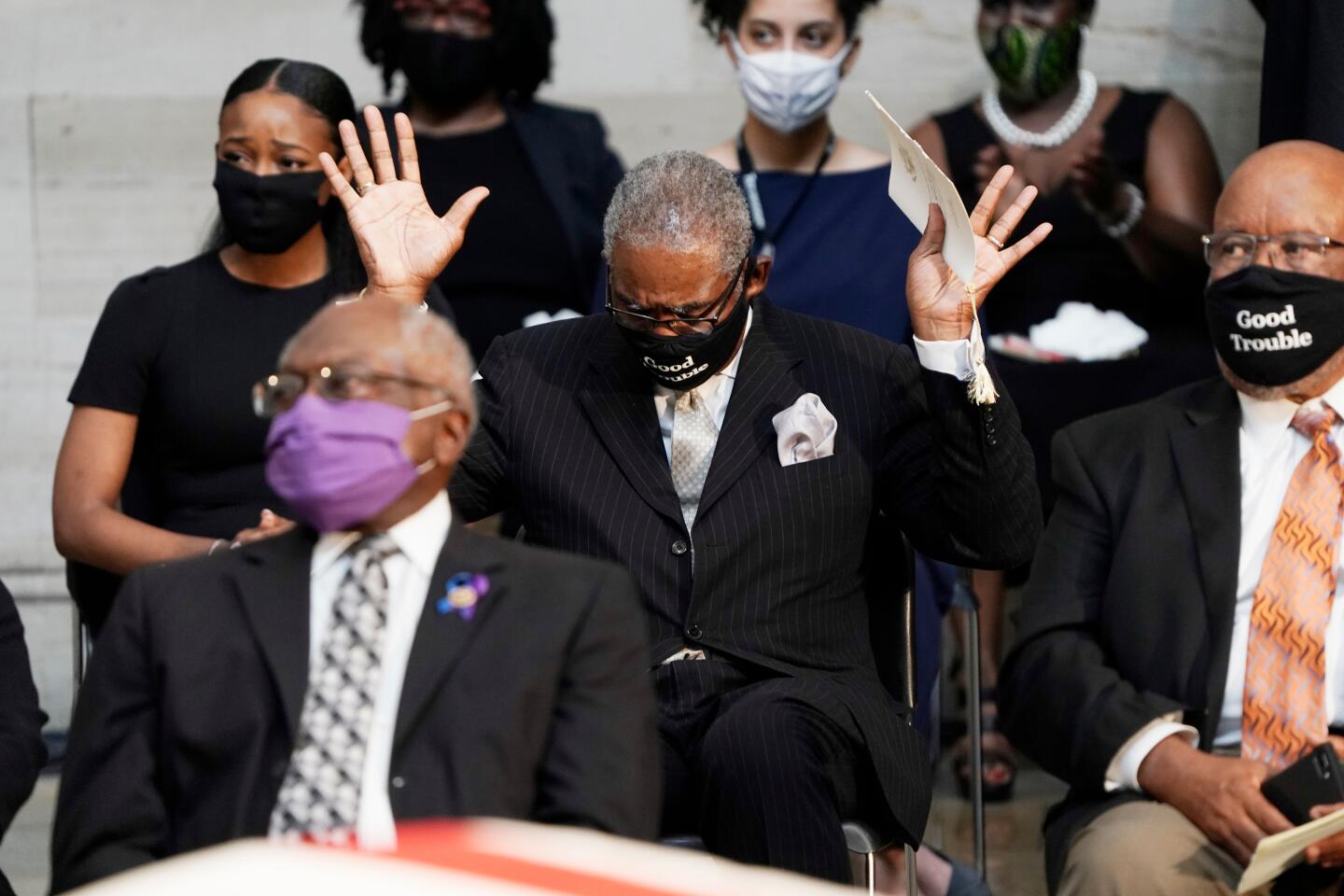

As dozens of members of Congress, Atlanta civic leaders and civil rights leaders joined Lewis’ family and staffers to pay their respects, hundreds of Atlantans braved the sweltering heat to gather outside and watch the service on a large screen.

Born the son of sharecroppers in 1940, Lewis was one of the original Freedom Riders who participated in sit-ins to desegregate lunch counters in Nashville.

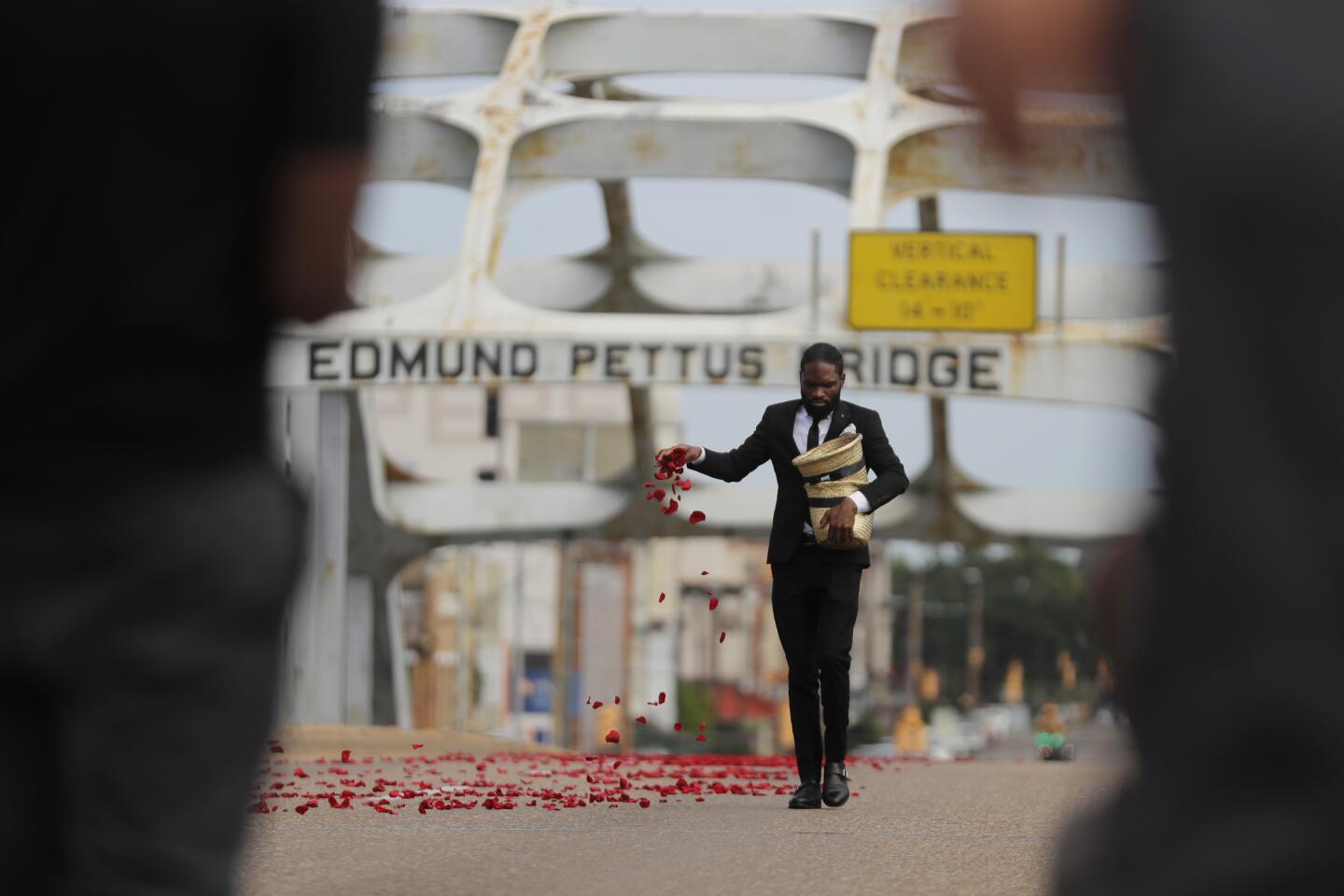

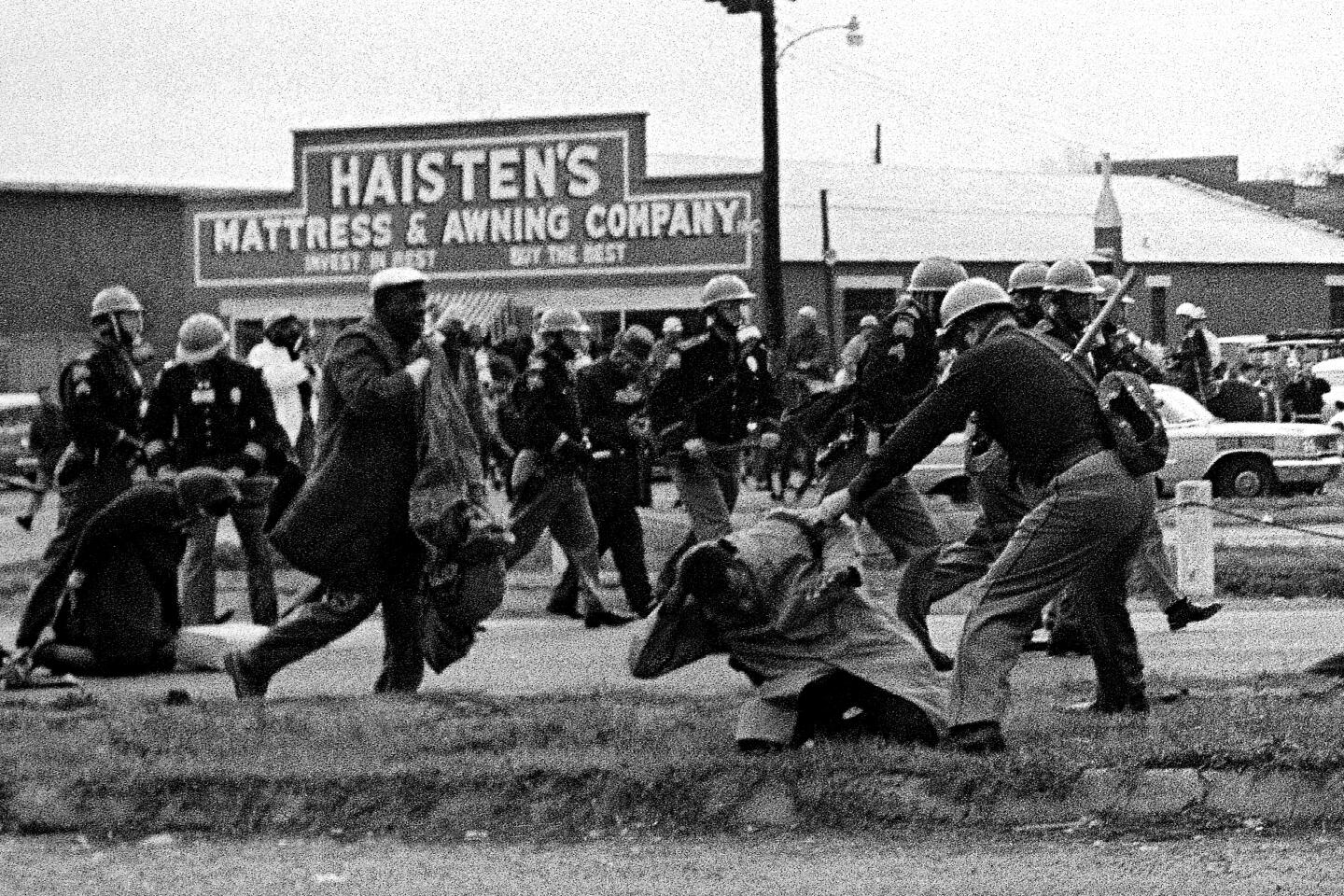

At the age of 23, he was the youngest speaker at the March on Washington for civil and economic rights for Black people. At 25, he was brutally beaten and struck in the head by state troopers as he tried to lead voting rights activists across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Ala.

Lewis went on to become a 17-term Democratic member of Congress and a mentor to younger politicians and civil rights activists, including Obama, who awarded him with the Medal of Freedom in 2011.

A trio of presidents, from both sides of the political aisle, offered eulogies, honoring Lewis’ historic role in fighting for voting rights and praising his capacity for compassion and forgiveness.

“Only John Lewis could compel three living American presidents to come here to celebrate his life,” the Rev. Raphael Warnock, Ebenezer’s senior pastor, who is running as a Democrat for a seat in the U.S. Senate.

“We are summoned here because we are in a moment when there are some in high office who are much better at division than vision, who cannot lead us, so they seek to divide us,” he said.

“At a moment when there is so much political cynicism and narcissism that masquerades as patriotism, here lies a true American patriot who risked his life and lived for the hope and the promise of democracy,” he added.

It was a not-so-veiled reference to President Trump, who did not attend the service. Trump didn’t give a reason, but Lewis had boycotted his 2017 inauguration and said he was not a “legitimate” president.

Earlier in the day, Trump took to Twitter to say that efforts to broaden mail-in voting as a result of the coronavirus would result in the most “INACCURATE & FRAUDULENT Election in history.” He proposed delaying the November election, which he does not have the authority to do.

Rep. John Lewis, 80, an associate of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. in the civil-rights movement and congressman from Atlanta, died Friday of cancer.

Speaker after speaker on Thursday said the best way to carry on Lewis’ legacy was to exercise the right to vote.

“What you can do, and I want to advise you and admonish you, to really give meaning to the John we love: Vote,” said Xernona Clayton, a civil rights activist and the godmother of Lewis’ son.

At times, the eulogies seemed to mourn not just Lewis, but the broader political spirit he upheld: of looking for the best in humanity, of working across the aisle, of seeking to listen and understand those he disagreed with.

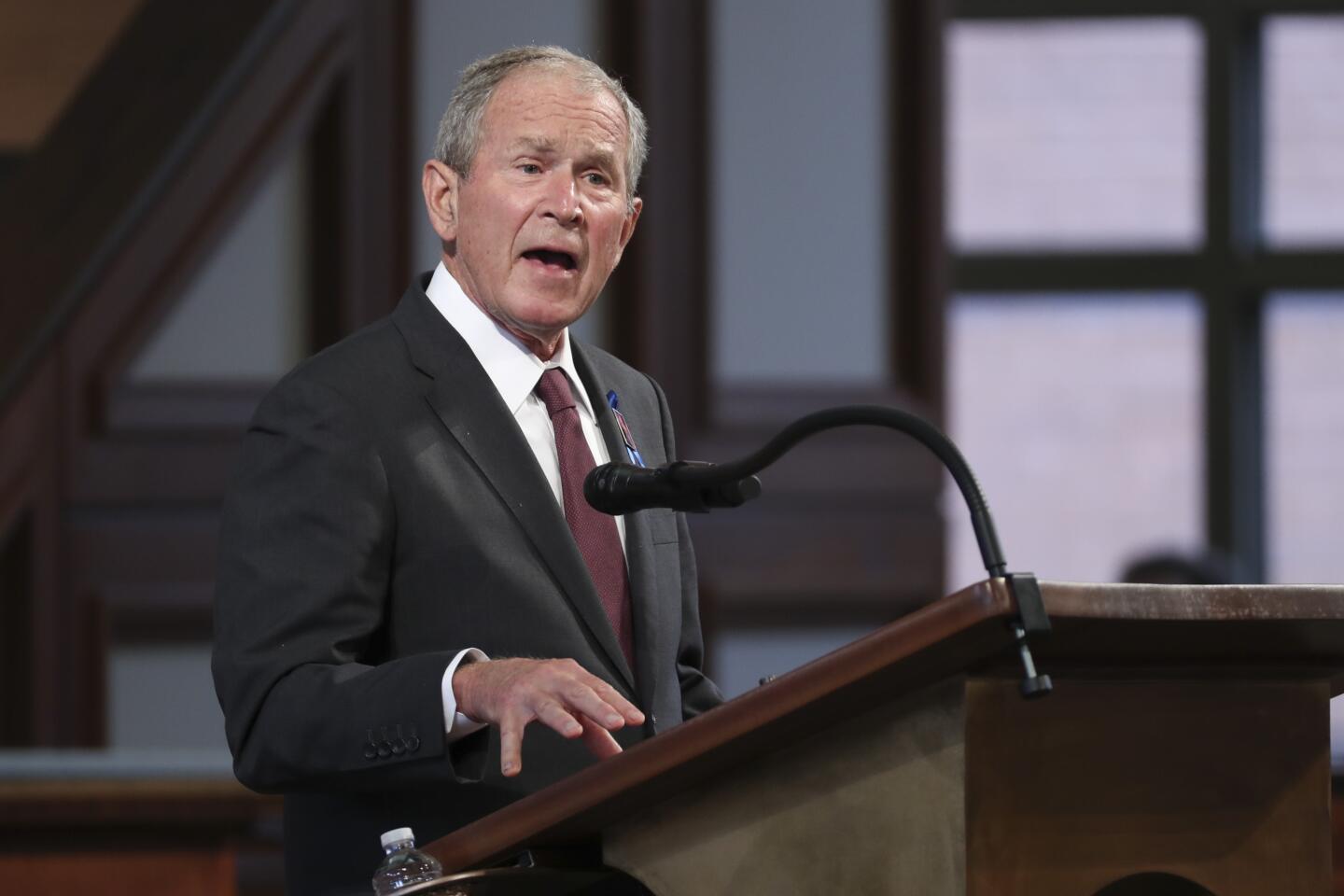

Former President George W. Bush, a Republican, acknowledged that he and Lewis did not agree on everything — Lewis had also boycotted Bush’s 2001 inauguration after the contested 2000 election — but the former president stressed that their difference of opinion was evidence of American democracy in action.

“We the people, including congressmen and presidents, can have different views on how to affect our union, while sharing the conviction that our nation, however flawed, is a good and noble one,” Bush said. “We live in a better and nobler country today because of John Lewis.”

Former President Clinton, in turn, praised Lewis’ unbridled commitment to persuasion as well as his capacity for forgiving his adversaries.

“Let’s not forget — he also developed along the way an uncanny ability to heal troubled waters,” Clinton said. “When he could have been angry, and cancel his adversaries, he tried to get converts instead. He thought his open hand was better than the clenched fist.”

Most famously, Lewis forgave George Wallace, Alabama’s segregationist governor who had sent the state troopers to Selma.

In referencing cancel culture, Clinton brought up a tactic that distinguished Lewis from some of the younger generation of protesters and civil rights activists, who reject compromise along with “respectability politics.”

In 2015, Lewis drew criticism from some activists in the Black Lives Matter movement when he tweeted: “I was beaten bloody by police officers. But I never hated them. I said, ‘Thank you for your service.’”

Lewis’ last public appearance, in June, was a visit to the Black Lives Matter Plaza in Washington.

In an essay written shortly before his death and published Thursday in the New York Times, Lewis wrote that he “just had to see and feel it for myself that, after many years of silent witness, the truth is still marching on.”

In some of his final written words, he paid tribute to the new generation of protesters.

“While my time here has now come to an end, I want you to know that in the last days and hours of my life you inspired me,” he wrote. “You filled me with hope about the next chapter of the great American story when you used your power to make a difference in our society.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.