In ‘God, guns and Trump’ country, simmering doubts about the president

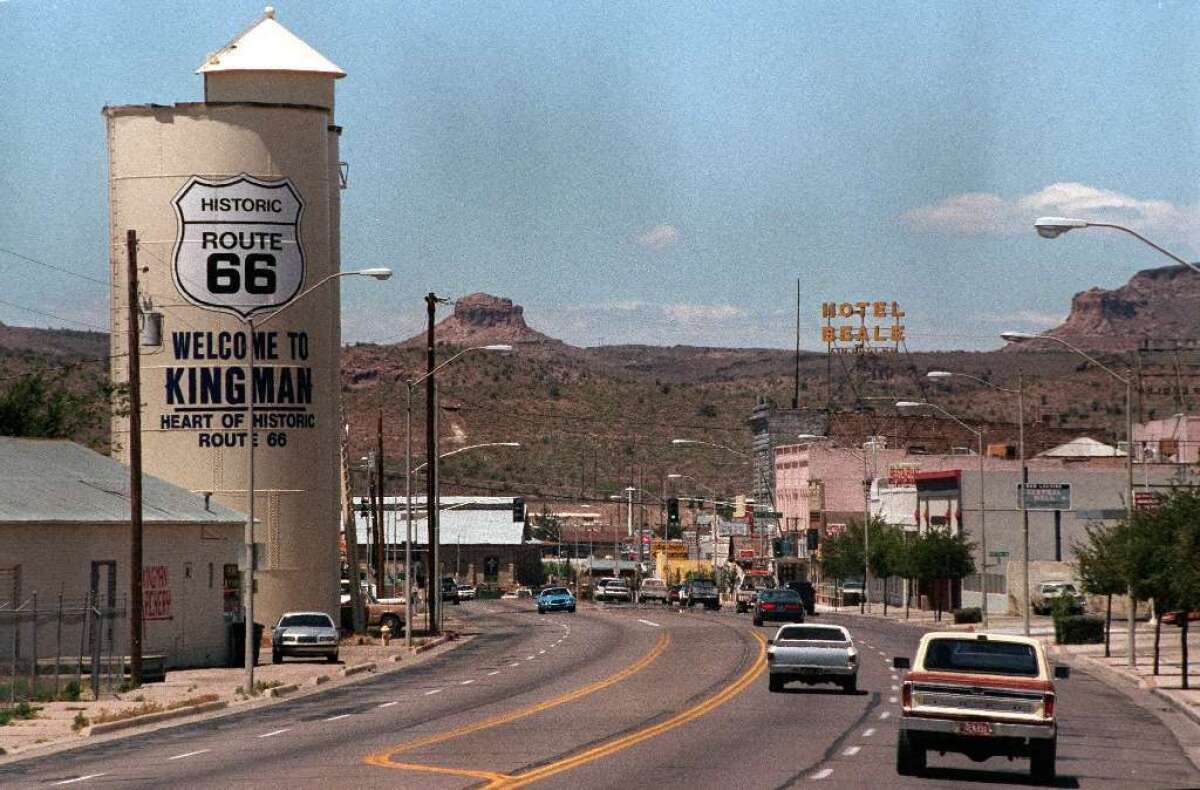

KINGMAN, ARIZ. — In this dry stretch of northwestern Arizona, Trump campaign signs dot the desert landscape, and Trump flags fly from the backs of dusty pickup trucks.

Last fall, an event called Trumpstock outside the town of Kingman featured a President Trump impersonator, a pro-Trump rapper and a menu of “MAGA Subs.” Last month, thousands of people blasted classic rock and circled Lake Havasu in a Trump-themed boat parade.

“This whole area is based around people who have the same thing in common,” said Alan Morris, a 36-year-old who participated in the parade. “God, guns and Trump.”

Yet now, as the nation confronts the COVID-19 pandemic, an economic recession and mass protests against police brutality and racism, some voters in the longtime Republican stronghold of Mohave County have begun to have second thoughts about the president.

“He’s an embarrassment,” said Ron Kennedy, 72. “And I voted for him.”

Data show that Arizona, which had seen a falling number of new coronavirus cases, recently marked its largest week-to-week increase since the pandemic began.

A veteran of the Air Force, Kennedy said he had grown wary of the president’s blunt style over the last few years. But the turning point for him came this month when protesters outside the White House were pushed back by authorities so Trump could walk to St. John’s Episcopal Church to be photographed by news crews.

“It turned me off,” Kennedy said. “Breaking up a peaceful protest just for a photo op.”

Recent polls show Trump now trails presumptive Democratic nominee Joe Biden in the presidential race — a reversal driven in part by the erosion of his once-commanding lead among white voters in battleground states such as Arizona.

To try to shore up support, Trump has visited the state three times in the last five months, including last week for an appearance at a Phoenix megachurch.

In Mohave County, a vast expanse of desert where 90% of the 212,000 residents are white and 73% of the vote went for Trump in 2016, there is still deep support for the president.

But he is facing new challenges here, such as assuaging concerns that he and the federal government have mishandled the coronavirus. The U.S. death toll of more than 127,000 is the highest in the world.

Four years ago, 57-year-old Keith Eaton viewed Trump as a refreshing change — an outsider who didn’t speak like a politician and appeared to act based on his gut.

“I just wanted to see what would happen,” said Eaton, who told himself: “At the very least it’s gonna be a circus we can watch.”

But Trump’s novelty has worn off, he said.

“The lack of leadership with this whole COVID thing, the lack of respect for the professionals that do this stuff … the last four months have turned me way, way more against him,” said Eaton, a firefighter. “There’s no way I would vote for him at this point. And a lot of guys I know feel the same.”

Eaton still expects Trump to win Mohave County, though by a lesser margin than he did four years ago.

Sam Scarmardo, head of the Mohave County Republican Party, said that if people have been changing their minds on Trump, it’s only because of “the left-wingers who are doing everything they can to destroy him and bring the country to its knees.”

“A lot of people think coronavirus was blown out of proportion to damage Trump,” he said.

Scarmardo said voters in Mohave County have a Wild West mind-set and are naturally drawn to Trump’s defense of gun rights, his disdain for government regulation and his vow to stop unauthorized immigration from the Mexican border, which lies 150 miles to the south.

The Trump administration’s effort to restrict immigration reaches far beyond the border, upending decades of U.S. policy and transforming the region.

In an interview in the back room of his Lake Havasu City gun store, where his four rescue dogs circled underfoot, he ticked off what he sees as Trump’s accomplishments: the rollback of Obama-era clean energy rules, the movement of the U.S. Embassy in Israel from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, and new policies that make it harder for migrants to seek asylum in the United States.

“He’s gotten more done than the last 20 presidents,” Scarmardo said.

His shop, Sam’s Shooters Emporium, features a life-size cardboard cutout of the president by the front door and a bulletin board that looks like Trump’s Twitter feed come to life. One poster questions the legitimacy of President Obama’s birth certificate; another compares the hijab worn by U.S. Rep. Ilhan Omar to a diaper.

In the bathroom are copies of former First Lady Michelle Obama’s autobiography — whose pages are used as toilet paper.

Such unapologetic displays of the kind of bigoted and divisive views embraced by Trump have never been a problem here, Scarmardo said.

“We don’t get much argument,” he said.

And yet, a few weeks ago, a surprising thing happened down the street from the gun store. A couple dozen people gathered for a Black Lives Matter protest.

More protests were held in Kingman, about 60 miles away.

At each event, participants were outnumbered by counterprotesters, some of whom were armed with rifles.

Government officials who monitored the event said they were less afraid of looting than of the protesters getting shot.

The demonstrations ended peacefully — and even sparked new kinds of soul-searching.

Retired police officer Jeff Page, 57, said the protests made him question whether racial bias had ever played a role in his own policing.

He concluded that it hadn’t.

“I did 28 years in law enforcement in Idaho, and I can tell you that there’s not one person that I ever worked with who wanted to go out and find somebody to kill or beat up,” he said on a recent afternoon at No Name Public House, a saloon in Lave Havasu City where he, his wife and some friends had gathered for beers.

“It’s been very painful,” Page said of the recent protests.

“It’s been horrible,” agreed his wife, Victoria.

He plans to vote again for Trump in 2020, but he said that his daughter, who voted for Trump four years ago, is undecided. She works for the local school district and is repelled by the president’s immigration policies that make life harder for Latino students and their families.

They have had conversations as a family about the topic, with Jeff arguing that illegal immigration is a law-and-order issue. But those talks don’t typically end well.

So the family came up with a solution, said Victoria: “We just don’t talk politics.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.