HONG KONG — What was supposed to be a banned event commemorating the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre became one of Hong Kong’s most unifying vigils in 31 years, as the old themes of accountability for massacre victims merged with new demands for democracy and autonomy in the territory.

Police had banned the annual vigil — which usually draws more than 100,000 people to mourn the Chinese pro-democracy protesters killed by soldiers and tanks in Beijing on June 4, 1989 — on grounds of public health, citing coronavirus concerns. They set up metal barricades around Victoria Park and mobilized 3,000 riot police officers to guard the city Thursday night.

Anxiety was in the air, given the new national security legislation issued by fiat in Beijing last week and the passage in Hong Kong’s legislature Thursday afternoon — over the objections of pro-democracy legislators — of a law criminalizing disrespect for China’s national anthem.

But when dusk fell, fears seemed to melt away as thousands of people streamed into Victoria Park, pushing the barricades over and turning them into benches, lighting candles and lifting cellphones alight with candle images as they sang pro-democracy songs in Mandarin and Cantonese.

Similar scenes sprouted in other parts of the city at the same time, with hundreds of people lighting candles in parks, outside subway stations, on the streets and along the harbor in defiance of police orders.

“You can’t run away,” said a 23-year-old student who gave only his last name, Lau, and who was taking part in his first Tiananmen commemoration. “If you don’t come out now, you might not be able to come out ever again.”

When the vigil was banned earlier this week, organizers called for “flowers blossoming everywhere,” a Chinese metaphor for a good thing spreading with no need for a leader. The number of people participating Thursday appeared to be fewer than in previous years, but they were spread around the city and seemed self-organized and more spontaneous than before.

In Victoria Park, there was no central stage as in days past. People sat in masked clusters of twos and threes, spaced several feet apart, streaming democracy songs on phones and tablets. One group sat on a government sign that read: “Observe the prohibition on group gatherings — together, we fight the virus!”

The annual vigil, started by patriotic pro-democracy groups in the 1990s, had been shunned in the past by younger Hong Kongers who felt less connected with mainland China. The slogans for a democratic China and an end to one-party rule were often dismissed as irrelevant to Hong Kong’s youth.

Hong Kong authorities have banned the annual Tiananmen Square massacre commemoration this year. But some are determined to remember — and resist.

But this year, increasing repression from Beijing has united two generations and disparate identities, forging fresh bonds between those whose lives pivoted in 1989 and those who weren’t even born at the time.

“We weren’t the generation to experience it,” said Ersir, a protester in his 20s who asked that his last name not be used for safety’s sake. Yet he came out to join the crowds in his neighborhood of Mong Kok.

“I came out because I thought the authoritarianism is too much,” he said. “We don’t want to break the law, but the system has pushed us this far. We don’t have a choice but to break the law.”

A couple who gave only their surname, Yuen, said they’d been coming to the protests annually for at least 20 years. They’d watched the massacre in central Beijing unfold on TV in 1989 and prepared to emigrate, selling their stocks and properties. But in the end, they didn’t go.

“I am too captivated by this place,” said the husband, 62. “I’ll never be able to leave.”

On Thursday, he and his wife arrived two hours early and sat down inside the park as soon as the barricades were pushed down, they said. Hong Kong was their home, and they planned to protest the loss of their rights as long as they were there.

“We are supposed to have the right to assemble,” he said. “It’s particularly important this year, because we are telling the government we will not be intimidated.”

His wife, 58, agreed. “Our outlook for Hong Kong is very bad. But we still have to do what we can. Do you only have kids if you know they will be successful people? No. You don’t know the future. All we have is hope.”

As usual, there was a video message from the Tiananmen Mothers, a group of mainland Chinese women who advocate on behalf of their slain children; a series of democracy songs; and a moment of silence at 8:09 p.m., signifying 1989. Then as the silence ended, a rush of new protest slogans filled the air: “National security law? No! Democracy? Now!”

Some of the younger protesters shouted, “Hong Kong independence, the only way out!” while the older ones cried, “Democracy for China!”

They all mixed together, then raised their candles in a sea of lights as they sang “Glory to Hong Kong,” an anthem penned during last year’s protests and often sung in defiance of the Chinese national anthem.

The police were conspicuously absent, with just a small group recording everyone who walked through the park entrance. There was a brief scuffle between plainclothes officers and some protesters across the harbor in Mong Kok after the vigil ended, but things were otherwise peaceful.

Meanwhile, in Beijing, Tiananmen Square was quiet all day, with the few visitors on the sprawling plaza monitored by police and armored vehicles. Some members of Tiananmen Mothers visited their children’s graves but had to register their IDs in advance and were watched by roughly 40 plainclothes and uniformed police, according to Hong Kong media.

Dissidents and activists on the mainland had been warned by state security to keep quiet on June 4, as usual, and many were taken on forced “vacations” — trips accompanied by police — to ensure they didn’t hold any gatherings.

Liu Jiacai, a former labor organizer and democracy activist from Hubei who has been imprisoned twice and often sent on “vacation” around June 4, said he would commemorate the day by fasting. It was the only feasible method of protest most mainlanders had left, he said.

“I can do this in any circumstance, even under their control. They keep asking me to eat, and I just say no, not today,” Liu said. “We will just quiet our hearts and reflect, after all these years, on everything we’ve done, and express pain and sorrow for those people who were lost.”

Beijing’s bottom line is sovereignty. Hong Kong is a ‘purely internal affair that allows no foreign interference,’ Chinese government spokesman says.

Another dissident based in Guangzhou who asked that his name be withheld said he’d posted a single flower emoji on WeChat on June 3 at 11 p.m. Within an hour, state security police called his wife, threatening to come to their home unless they deleted it.

He obeyed, then posted a blacked-out square instead.

“It’s an image of darkness,” he said. That was all they could express.

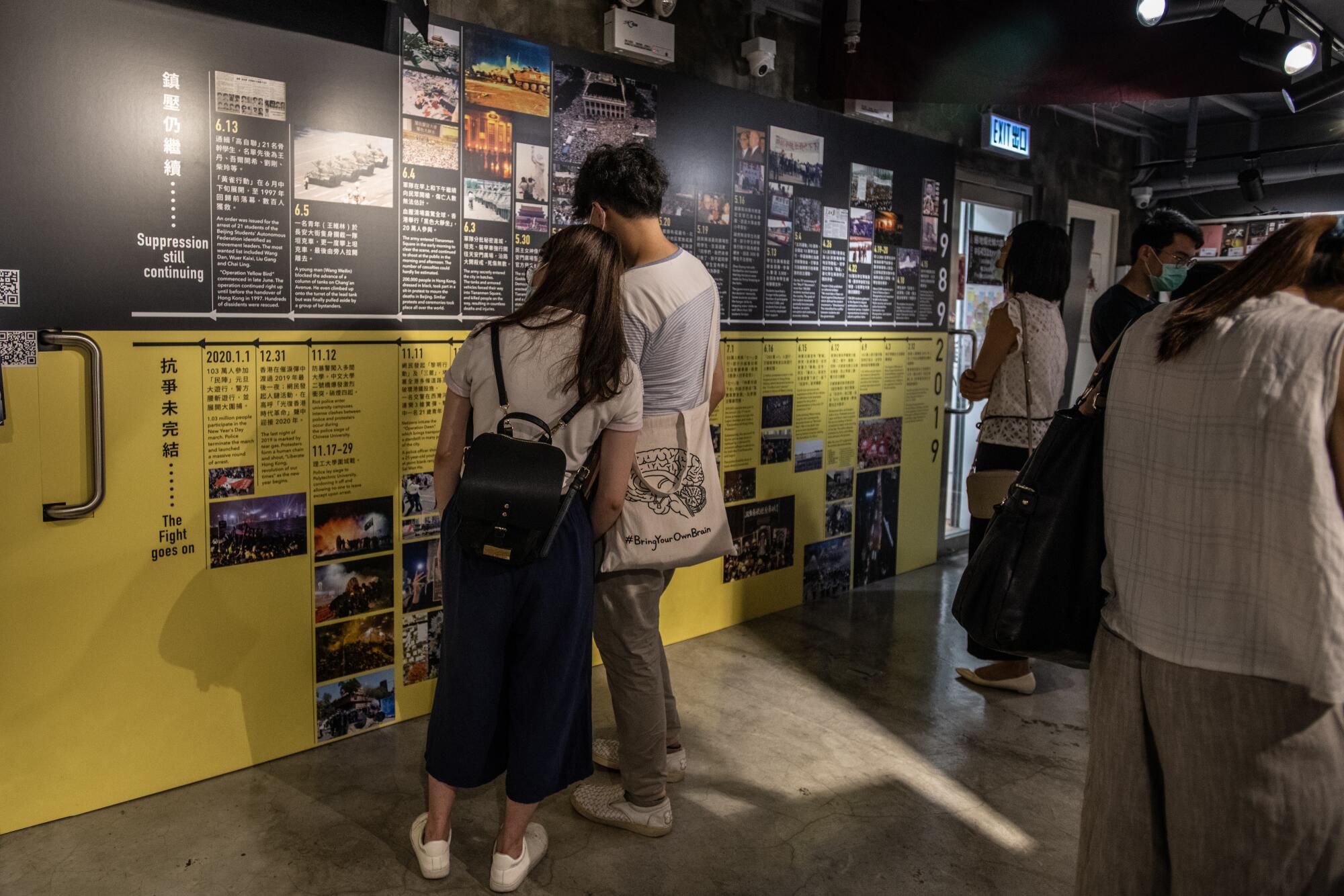

Earlier in the day, visitors filled Hong Kong’s June 4 museum — a small space usually aimed at teaching mainland Chinese visitors about the massacre’s history. This year it has hosted mostly young Hong Kongers.

Amy Chan, 17, brought her brother Aaron, 10, for the first time. They browsed a special exhibit comparing the 1989 protests to Hong Kong’s pro-democracy movement, complete with maps of Hong Kong and Beijing marking where protesters in each place had been shot, beaten or killed.

“June 4 is history, something we can’t forget,” said Amy. She worried that this was her last chance to visit the museum and that she might be punished by authorities for speaking about June 4 online or in person in the future because of the national security legislation.

So she brought her little brother along — while it was still possible.

“Children need to learn about this. It’s not about whether it was gruesome,” she said. “He has the right to know what happened in society then. And I want him to understand that humans are entitled to basic human rights. People should be able to express what they think.”

They paused at an exhibit dedicated to Wang Nan, a high school student who was shot and killed in Tiananmen Square. His mother had donated the banner he’d waved in the square, which said, “The people support you,” and the red motorcycle helmet he’d been wearing when he was shot. Amy pointed out the bullet holes in the helmet.

“I’m a little scared,” her brother said. “I’m scared that a tank might crush me.”

But he also repeated what his sister had taught him: “As long as we join forces with one heart, there is no need to be afraid.”

Times staff writer Su reported from Shanghai and special correspondent Chor from Hong Kong.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.