Muslims worldwide adjust monthlong Ramadan plans due to coronavirus risks

TRIPOLI, Lebanon — Sitting in the shade of Tripoli’s Mansouri Great Mosque, Issam Jadeed, an unemployed dessert maker, scowled at passersby asking if they could go inside.

His answer, like so much else these days, involved the global coronavirus outbreak.

For the record:

2:33 p.m. April 23, 2020An earlier version of this article misspelled the name of the Birkeh Mosque.

“It’s closed. Imagine! It’s almost Ramadan and we can’t go to pray because of this corona,” he said, referring to COVID-19 as if he were talking about a frustrating family member. “But it’s wrong to do this. This is the House of Allah. Inside, we would be aamen, secure.”

It is a time of frustration for many Muslims in Lebanon’s second largest city as well as millions around the world about to mark Ramadan, the holy month of fasting, which begins Friday.

In a time of pandemic, religion, the sanctuary for so many in Iraq, has been hit hard. The faithful are live streaming services, praying in private.

Normally during Ramadan, the mosques of Tripoli, more than any other time of year, dictate the city’s rhythms and anchor its rituals.

But authorities shuttered them weeks ago when fears of the coronavirus emerged elsewhere in the Middle East, including Iran, the disease’s regional epicenter. And the closures are set to continue, making for what many of the 1.8 billion Muslims worldwide consider an incomplete Ramadan.

“The heart of the believer is tied to the mosque. Our hearts are burning from this situation. Not just burning — they’re a volcano,” Sheik Firas Balloot, head of the religion section in Tripoli’s Islamic endowments department, said during an interview this week. “If this fire wasn’t there, then we have no faith; we’re stone. But there is a common good, and issues of health.”

Ramadan, the holiest month in the Islamic calendar, is traditionally a time of religious introspection, unveiling new truths to the believer through the physical hardship of fasting from sunrise to sunset. But it’s also a time of community, of celebrating the bonds of the Muslim faithful, with the neighborhood mosque at its nexus.

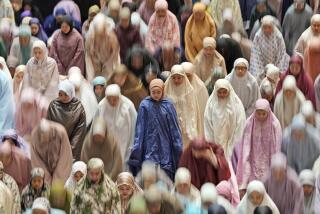

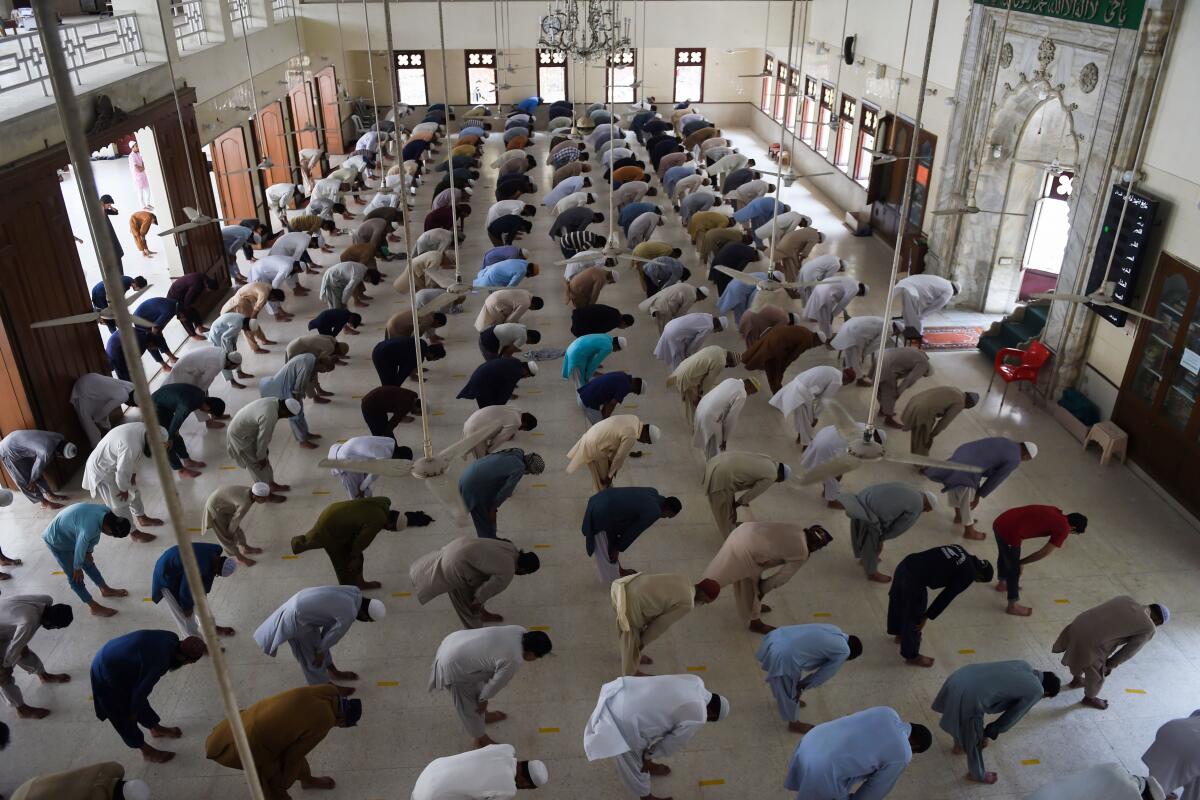

In Tripoli, Ramadan slows the daytime tempo of this city’s 730,000 people. The adhan, the call to prayer, reverberates in a canon from the city’s 100-plus mosques; hundreds of thousands of people — including many usually non-observant Muslims — pack them to capacity to worship together.

Sunset kicks off the nocturnal switch that is the hallmark of Ramadan living: Families and friends meet to break their fast in iftar meals, then head to the mosque for taraweeh, evening prayers that happen exclusively in Ramadan and which can last well into the night. From there, they often crowd into sidewalk cafes and restaurants hidden in the warrens of Tripoli’s ancient markets for an argileh pipe and suhoor, a predawn meal. They return once again to the mosque to usher a new day of fasting with sunrise prayers.

Much of that will be upended by the coronavirus, which as of Wednesday was confirmed to have infected 682 people of Lebanon’s population of roughly 6 million and left 22 of them dead, according to figures from Johns Hopkins University. Turkey and Iran, each with populations of some 82 million people, have a combined tally of more than 184,000 cases.

Lebanon’s government, fearing the contagion would inundate its decrepit health system, banned gatherings and sealed off most establishments since early March. A nightly curfew that began at 7 p.m. and ran till 5 a.m. has been shifted to begin an hour later, giving little time for the special religious activities interspersed throughout the month.

“I can’t tell you only one thing I’ll miss in this Ramadan. I miss everything already,” said Osama Shehadeh, imam of Tripoli’s Birkeh Mosque, in a phone interview.

This year, Shehadeh said, taraweeh are canceled; he won’t return to the mosque after delivering the sunset adhan. He also won’t hear the voices of young boys arrayed before dawn prayer congregants as they practice tajweed, the art of recitation of Muslim religious texts.

The same applies to the Sayeda Khadija mosque, an active house of worship even during normal times but which more than doubles its attendance during Ramadan, according to its imam, Abdul Rahman Khadher.

“Every year, we organize study circles, or Ramadan competitions, so families participate in memorizing the Quran, and children win prizes for religious knowledge — events to deepen our connection with worshipers,” Khadher said in a phone interview. He said the mosque also set up charity drives and distributed iftar meals to the less fortunate.

Much of that has been canceled, but both religious leaders were determined to turn the crisis into an opportunity. Shehadeh had organized for young people to film themselves for the tajweed competition; Khadher had set up a religious educational web series, and aimed to broadcast study sessions on the mosque’s social media channels. Money normally used for prizes would be diverted to more social assistance.

“Look, I’m sad, but I’m using it to do work because my sadness won’t help anything,” Shehadeh said. “Opening the mosque to believers now is like driving passengers in a bus with no brakes. If anything happens to the people inside, I’m responsible before Allah.”

Balloot said that since the beginning of the lockdown some people in Tripoli have defied the injunction on Friday prayers and have worshiped in front of mosques’ gates or forced their way inside.

“For me, the Islamic endowments department is participating in a crime,” said Abdul-Rahman Faeq, a spice seller in Souq al Attareen, the ancient Perfumers’ Market. “Yes, they should act to stop the virus, but not block the door to worship. We’re in times of hardship and should turn to Allah.”

Ramadan is normally boom time for merchants, similar in many ways to the United States’ pre-Christmas shopping rush. But few expected the bonanza to materialize this year.

“Does this look like Ramadan to you? This is the first day I’ve opened in weeks. I haven’t sold anything yet, and it’s already afternoon,” said Suhaib Sheikh, a 23-year-old manager of a shoe store, as he stared wistfully at the few reluctant shoppers nearby.

Business was better at Hallab 1881, a world-famous Lebanese dessert shop based in Tripoli — but it was still a strange time, said Zaher Hallab, one of the company’s board members.

“We wait all year for Ramadan, our customers too. It’s a matter of heritage, with a connection between Tripoli and the sweets of the season,” Hallab said in a phone interview.

Every year, the company’s flagship location, an ornate building in the heart of Tripoli known as Kasr el Helou, or “The Palace of Sweets,” would host suhoor stations on the balcony. Patrons could enjoy a meal and follow it up with karabeej, semolina rolls stuffed with pistachio or walnut; ward al-sham, heavy cream nestled between syrup-infused layers of filo dough; or qamar al-din, a seasonal apricot beverage.

“Of course the whole experience is not there,” Hallab said, adding that the store had set up what he called a “walk-through” for sanitary pickup of desserts, one of several workarounds to keep customers coming.

Many of the city’s denizens seem unconcerned with the requirements of a Ramadan under the coronavirus.

In Bab al Ramel, a Tripoli neighborhood where patrons during Ramadan bounce around mosques, cafes, bakeries and shops until dawn, the mood was one of defiance.

“Ever since we were born, we know that this area here in Ramadan never stops,” said Mohammad Dniyeh, one of the neighborhood’s mukhtars, or local government representatives, in an interview in his office in Bab al Ramel.

A steady trickle of the neighborhood’s inhabitants crowded into the cramped room; those few with masks pushed them under their chin when they walked in.

“Already many people aren’t obeying the lockdown. I guarantee you, when Ramadan starts, 90% of people won’t listen.”

Near him, Mustafa Walid, a burly day-laborer visiting Dniyeh’s office to fill out paperwork, scoffed.

“Ninety percent? Make that a hundred. We’ve had enough of lockdown: physically, spiritually and financially,” he said, punctuating the last three words as he walked out.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.