Coronavirus outbreak squeezes finances of Democratic grass-roots donors

WASHINGTON — Well-to-do donors gathered in August at the sprawling Charlotte, N.C., home of Erskine Bowles, a former chief of staff to President Clinton, where they nibbled finger food, sipped wine and listened to Joe Biden.

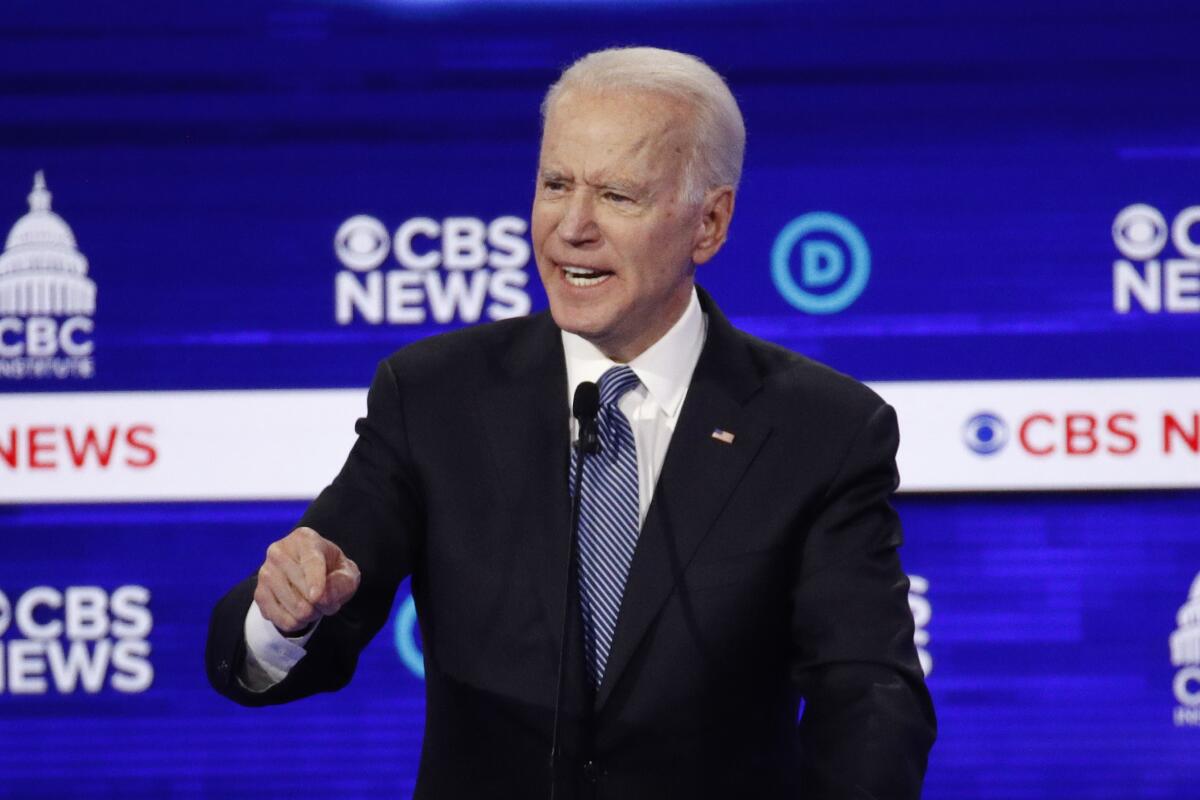

Last week they again joined Bowles and his wife, Crandall. But this time it was for a far less intimate affair: a fundraiser held by video conference that Biden, the presumptive Democratic presidential nominee, joined from the makeshift studio in the basement of his Delaware home.

The coronavirus shutdown has forced Democratic donors to forgo the opulent fundraisers that allow them to rub shoulders with powerful elected leaders and candidates.

During the Democratic primary, progressive candidates and activists condemned big-dollar affairs. But they have become a practical necessity for Biden that is sure to rankle progressives, who point to an army of grass-roots donors contributing small amounts online as the antidote to big money in politics.

As the coronavirus punishes the economy and swamps the healthcare system, the poor and middle class are among the hardest hit, all but ensuring that Democrats’ wealthiest donors will have to bear the cost of the party’s effort against President Trump in November.

Bowles said that the pandemic has delivered “economic hits ... to everybody, regardless of their station” but that the Democratic donor class remains engaged.

“When I say raising this money was easy, it really was,” he said of the virtual event.

Some deep-pocketed Democrats embrace the turnabout.

“There’s nobody more patriotic than Democratic donors who write large checks, because they are giving against their own self-interest,” said Kirk Wagar, a Democratic donor, former ambassador and fundraiser who was Florida finance chair for President Obama’s campaign.

The role money will play in the presidential campaign is complicated and may not be the arms race that it has been in previous contests. But just how much of it will be needed in an abbreviated campaign that has ground to a halt because of the virus is not clear, especially in a contest between a president who dominates the news media landscape and a former vice president with near universal name recognition.

Wealthy donors were always going to play a major role financing the general election. But Biden did a poor job raising money during the primary and was running perilously low on funds before his big victory in the South Carolina primary upended the race.

He’s now up against Trump and a Republican National Committee that have already stockpiled $240 million as of the end of March. Biden reported Monday that he took in $46.6 million in March, though less than half of it came from small-dollar donors who gave $200 or less. And according to figures previously released by the campaign, most of that, $33 million, was raised in the first half of the month before financial markets plummeted and much of the country went into some degree of lockdown.

He’s since enjoyed a surge in online fundraising, with the campaign saying it raised more than $5 million in the days surrounding endorsements from Obama and progressive former rivals Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren. But Biden’s financial concerns are enough that he’s yet to announce any significant staff hires across many key battleground states.

And the campaign hasn’t trumpeted months’ worth of television or digital ad buys ahead of the fall campaign.

“Trump is raising hundreds of millions of dollars, and we’re definitely going to need the help of big-dollar donors to beat him — it’s just the reality,” said Marc Stanley, a Democratic donor and trial attorney from Dallas.

Although Trump’s handling of the coronavirus pandemic appears to have lowered his approval rating, some Democrats are worried that his ubiquitous presence leading daily press conferences is overshadowing Biden. That increases the need for advertising that offers counterprogramming to the nightly story line emerging from the White House.

“Trump is in people’s living rooms for more than an hour every day. Biden is less visible, and there’s a lot of deep concern about where we end up,” said David Brock, co-founder of the Democratic group American Bridge, which launched a $15-million ad campaign last week targeting Trump’s handling of the coronavirus crisis.

“The question mark is the small-dollar donors,” Brock continued. “It stands to reason that that pool will shrink as you have rising unemployment, their hours cut and young people going into the job market facing lower prospects.”

Not everyone is convinced that the fallout from the pandemic will depress fundraising, both low dollar and high.

“Look, I would love to tell you that large donors are going to come and save the day,” said Steve Westly, a Silicon Valley venture capitalist who is raising money for Biden’s campaign.

Attacking China — and linking Joe Biden to China — has become central to Trump’s reelection campaign strategy. Biden responds today.

“I think you are going to see a lot of people coming behind Joe Biden in this race. The reason is they are pissed off. They are pissed off at the president’s handling of the coronavirus. Not only might they be losing their loved ones, or getting sick themselves, but the economy is in turmoil.”

One remaining question is the extent to which former New York Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg invests his $60-billion fortune in the race. Bloomberg, who spent $1 billion on his own failed attempt at the Democratic nomination, previously committed to running an outside group that would take on Trump. He shelved those plans but donated $18 million in remaining campaign funds to the Democratic National Committee.

Westly said the question for Bloomberg, 77, is how he wants to be remembered.

“I think everybody of that stature cares about his legacy,” said Westly. “Does he want the narrative to be ’I unsuccessfully spent $1 billion on my own campaign’? Or would he rather have it be ‘I spent $2 billion and stopped Donald Trump from winning’?”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.