Combative and defiant, CIA psychologist reignites torture debate at 9/11 hearings

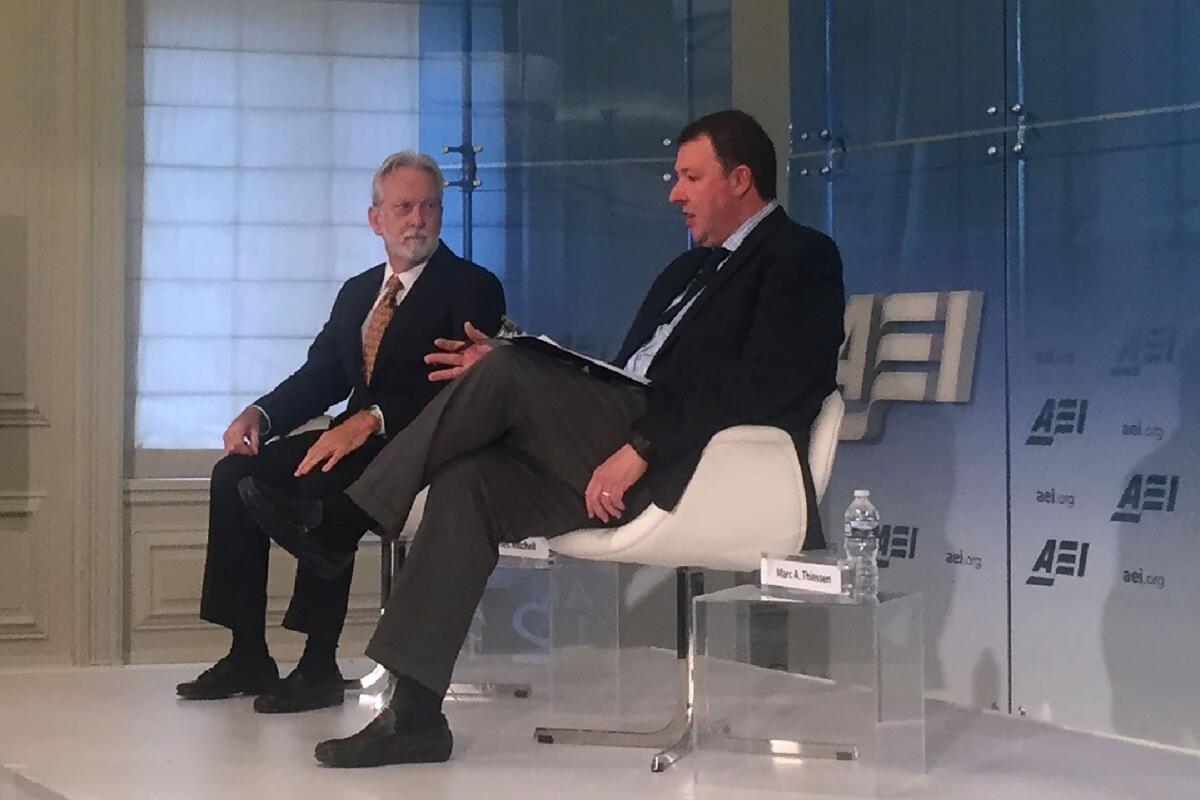

GUANTANAMO BAY NAVAL BASE, Cuba — James Mitchell, the psychologist who devised the CIA’s post-Sept. 11 interrogation program, is a complicated figure.

He labeled some of his own actions monstrous and horrifying but said he would do them again.

He said he almost liked Khalid Shaikh Mohammed, the man who proclaims he dreamed up the Sept. 11 attacks, and called him charming, smart, funny and charismatic. He once held Mohammed’s hand when they talked.

He also threatened to kill Mohammed’s son.

Mitchell ended nine days of often contradictory testimony here Friday in preliminary hearings for the murder trials of Mohammed and four co-defendants who are accused of conspiring to kill nearly 3,000 people on Sept. 11, 2001, when terrorists hijacked jetliners that crashed into the World Trade Center, the Pentagon and a field in Pennsylvania.

Mitchell has become the face of the interrogation program that critics have deemed torture in large part because of a combative personality. He ran through a range of emotions on the stand, from sorrow through vengeance.

He acted, he said, out of a deep sense of loss and for those whose relatives were killed on Sept. 11. He personifies the debate about the war on terrorism, and people respond to him as much according to their own views as his.

“Amazingly shameless,” said Mark Denbeaux, a Seton Hall law professor who defended the first man Mitchell waterboarded.

“We’ve moved from the banality of evil to the vanity of evil,” said Zeke Johnson of Amnesty International.

Relatives of the victims, interviewed here at the U.S. naval base at Guantanamo Bay, see things differently.

Marc Flagg, an airline pilot whose parents died on the plane that crashed into the Pentagon, regards Mitchell and his fellow psychologist John “Bruce” Jessen as overlooked heroes.

“Our country owes him a debt of gratitude that I don’t think they can pay him enough for,” Flagg said. “Most Americans have no idea what Drs. Mitchell and Jessen have done for us.”

Ken Fairben, a paramedic whose son was killed when the south tower of the World Trade Center collapsed, was moved when Mitchell testified that he did what he did to protect the U.S. “He was there for the victims and their families,” Fairben said. “I could have hugged the man.”

On Friday, Mitchell completed his testimony the way he had started it, berating the defense attorneys. “Every chance you get, you slander us in the press,” he said.

When pressed on the long-term effects of torture on one of the defendants, Walid bin Attash, who is accused of training the Sept. 11 hijackers, Mitchell said he could tell Bin Attash was fine just by looking at him across the courtroom from 30 feet away.

“He’s been sitting there smiling at me,” Mitchell said.

Neither Mitchell nor the interrogation program is on trial, though at times it has seemed that way.

After Sept. 11, the entirety of the American national security apparatus was reoriented to a single task: stopping the next attack. The panic was nearly total.

The United States swept up a wide array of men: good and bad, cabdrivers, cooks, farmers, terrorists and murderers; fathers and sons, friends and enemies. Often, the government couldn’t tell one from another.

For the presumed worst of those captured, the CIA set up an ad hoc network of secret prisons around the world.

The agency hired Mitchell and Jessen, retired Air Force officers who had trained military members how to resist harsh interrogation, to set up the interrogation program.

They developed a program — ostensibly based on a reverse-engineering of that resistance training — that was designed to make prisoners comply. Some of these “enhanced interrogation techniques” were exceptionally brutal.

Defense attorneys contend that the harsh treatment made subsequent confessions from their clients involuntary — and thus not admissible in court.

An analysis by the CIA’s Office of Medical Services concluded that the program “had been little more than an amateurish experiment, with no reason at the outset to believe it would either be safe or effective.”

On the stand, Mitchell dismissed this and other criticisms, then provided gruesome, detailed descriptions of the system and the brutal methods he employed.

Almost everyone who watched any of the waterboarding sessions he and Jessen devised was overwhelmed — including, he said, himself.

Mitchell, 67, is now retired and living in Florida, where he was raised by his grandmother. His doctorate, from the University of South Florida, was in clinical psychology. His dissertation compared the roles of diet and exercise in reducing hypertension.

He is an outdoorsman. He fishes and is planning an ice-climbing expedition to Alaska. He’s fit and trim, his eyes sunk deeply into an angular face.

Mitchell characterized the Guantanamo tribunal hearings as “pettifoggery, an over-emphasis on petty details.”

A recent Amazon Studios movie about the torture program, “The Report,” portrays Mitchell as a despicable incompetent. A brief clip from the film was played at the hearings. Mitchell called the movie — and the Senate investigation on which it was based — “a partisan hack job.”

He has an unusual behavior on the stand. He jokes, cries, critiques, extemporizes — and winks. A lot.

One defense attorney, James Harrington, finally asked whom he was winking at. He said it was his lawyer in the back of the room. Then he winked at Harrington.

Mitchell can often appear resentful of almost everyone. He said the CIA threw him and Jessen “under the bus,” basically blaming them for the torture program. (Over the years, the government paid their company more than $80 million.)

He did only what he was asked to do — make recommendations on what coercive methods might work — but never had the authority to implement them, he said.

“The president’s position, as I recall what I was told, is that they’re not going to let Al Qaeda set off a nuclear weapon in one of our cities or crash another series of airplanes into a bunch of our buildings, and the gloves were off,” he said.

He described other people in the interrogation program as duplicitous liars, bureaucrats, bad scientists and misanthropes. He said most of them did not understand the program or how to implement it. He repeatedly said that he used good science and that they did not.

On his good days on the witness stand, Mitchell acted like everybody’s uncle, as he described himself. “I’m an old guy and I’m a little bit slow,” he said. He can be accommodating and responsive. He is articulate, well read.

On other days, Uncle Jim seemed haggard and exhausted. He was combative and truculent, challenging questions even before they were finished being asked.

It often seemed as though he was tortured himself. On Thursday, asked to read a report another interrogator had written, he started to reply, then interrupted himself to say, “It’s about the stories we tell ourselves.”

Yes. Yes, it is.

McDermott is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.