As Iraq reels from U.S. strike, its politicians turn against Washington

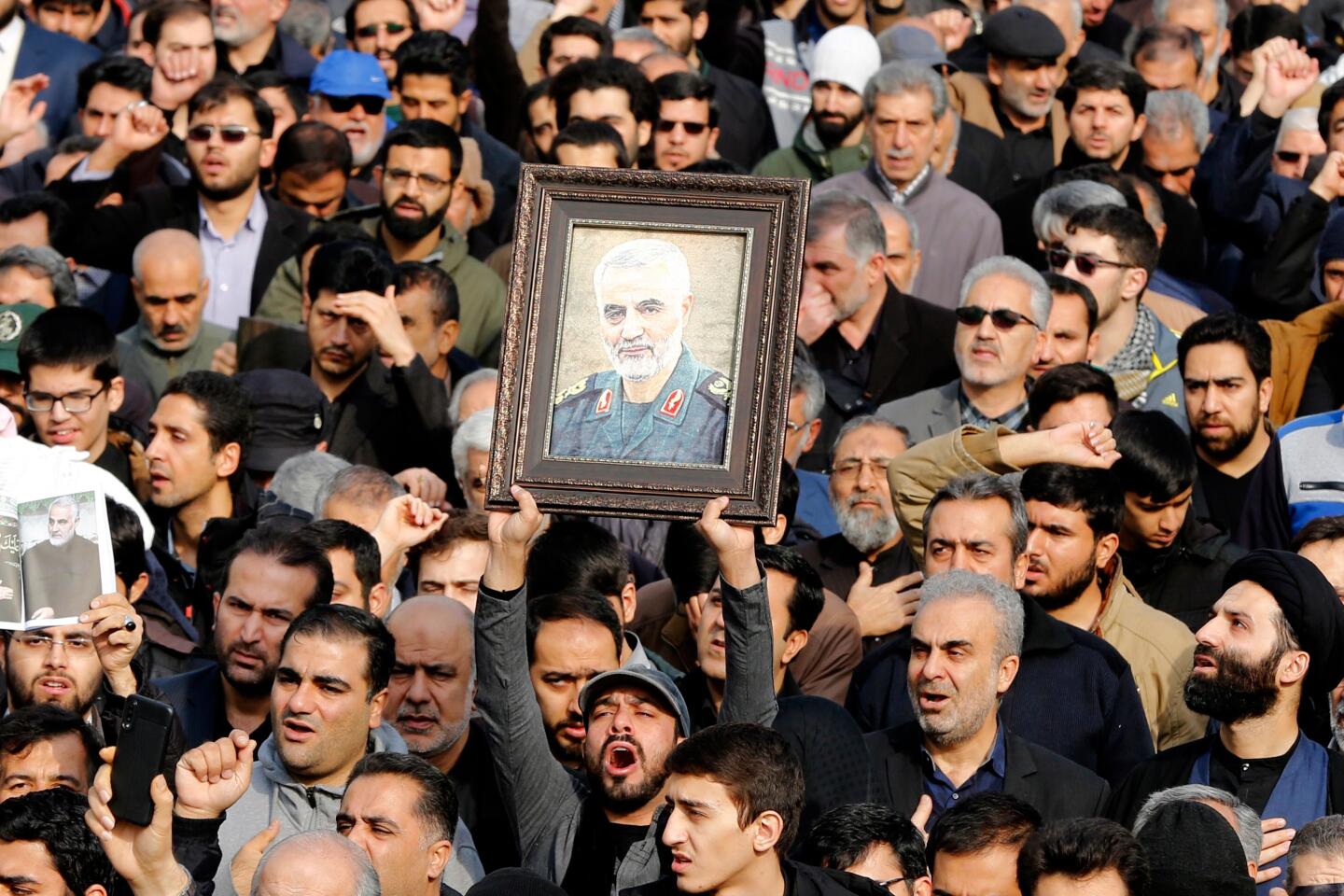

BEIRUT — The crowd thronged around the two coffins, one draped in the Iraqi tricolor and the other wrapped in the red, white and green of the Iranian flag. Behind them, thousands trudged alongside a procession of trucks, chanting, “There is no god but God, and America is the enemy of God.”

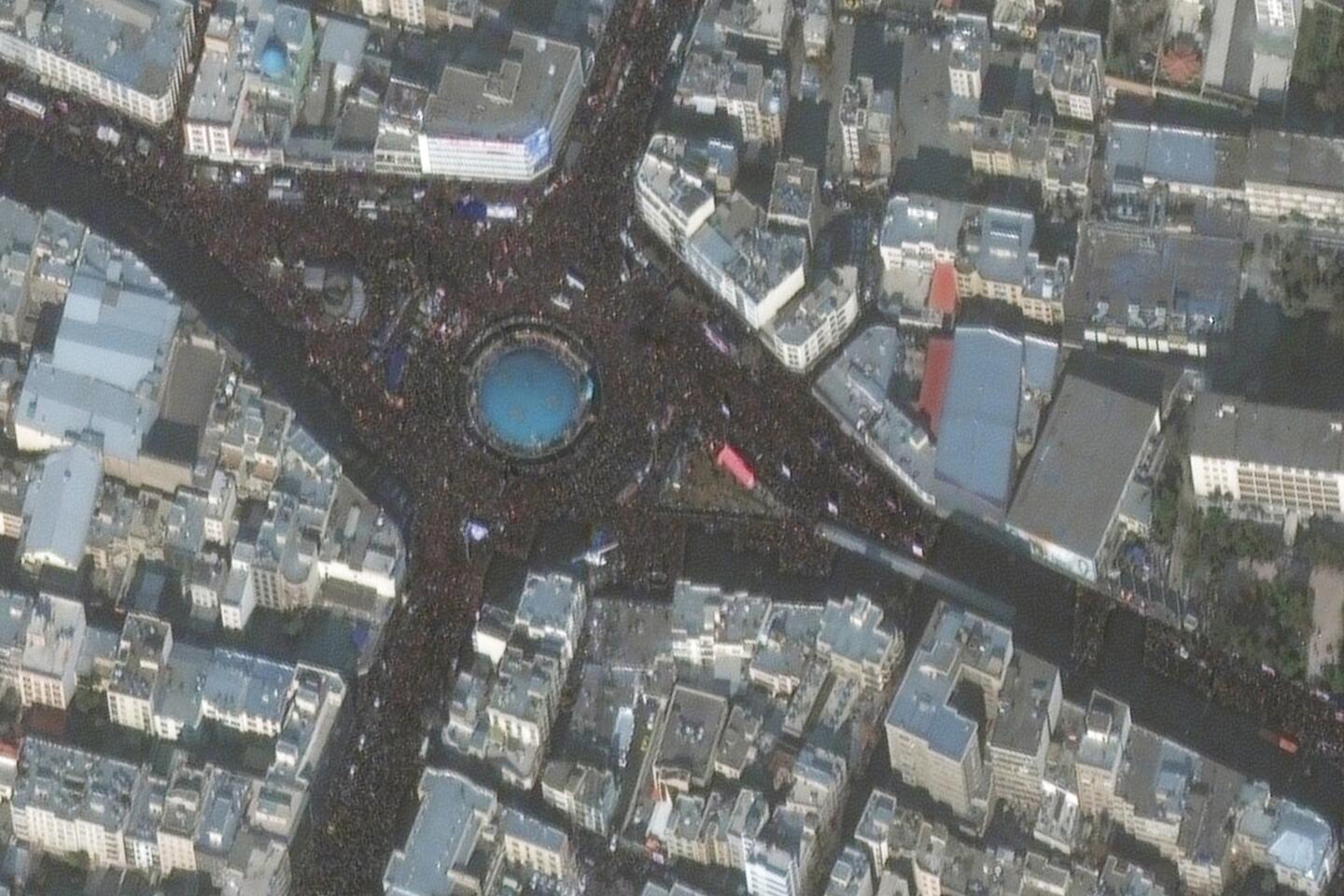

Among those at the fore in Baghdad’s Hurriya Square on Saturday morning were Iraqi government officials once considered friends of the U.S.: Adel Abdul Mahdi, Iraq’s caretaker prime minister; Nouri Maliki, a former longtime prime minister pushed into power by Washington; and Faleh Fayyad, who met with U.S. Defense Secretary Mark Esper in October. They and other Iraqi politicians were in attendance to mourn those killed Friday in a targeted U.S. drone strike near Baghdad’s international airport.

Their presence was but one measure of the anger raging through Iraq’s leadership class in the aftermath of the attack ordered by President Trump to kill Iranian Maj. Gen. Qassem Suleimani, the commander of Tehran’s elite Quds Force and mastermind behind Iran’s regional military strategy. Also slain were Abu Mahdi Muhandis, the deputy head of a bloc of Iran-backed Iraqi militias, and several others.

For many in Iraq, the attack marks a death blow to U.S. influence in the country.

“I’m stunned. I’m speechless. This is a declaration of war,” said Muwaffaq Rubaie, a former Iraqi national security advisor under Maliki, in a phone interview on Saturday.

“This is the beginning of the end of the U.S.’ presence in Iraq.”

Hours after the funeral procession, Trump, who has claimed he ordered the airstrike to prevent future attacks, tweeted an aggressive warning to Iran, saying “The USA wants no more threats!”

“Let this serve as a WARNING that if Iran strikes any Americans, or American assets, we have targeted 52 Iranian sites (representing the 52 American hostages taken by Iran many years ago), some at a very high level & important to Iran & the Iranian culture, and those targets, and Iran itself, WILL BE HIT VERY FAST AND VERY HARD.”

Ever since the Bush administration ousted longtime strongman Saddam Hussein in 2003, Iraqi political life has required a balancing act between Tehran and Washington. Iraq’s economy, its access to oil markets, even the selection of its premier and president have proven a function of a hard-won battle of wills between the bitter adversaries.

On one side has been the U.S., the architect of Iraq’s post-Saddam order, an ally in the country’s existential fight against Islamic State militants and the guarantor of Western involvement in its economic development. On the other side is Iran, far closer both in proximity and in shared religion with Iraq’s majority Shiite Muslims.

Iran is Iraq’s next-door neighbor, with a 900-mile border between the two. And though it once fought an almost eight-year war against Hussein, Iran became one of Iraq’s top trading partners after the 2003 U.S.-led invasion of Iraq.

The kinship is more than economic. Every year, more than 10 million Iranian Shiites stream into Iraq for the annual Arbaeen pilgrimage.

Iran has wielded its influence to infiltrate almost every level of Iraqi society. Indeed, it used religious fervor in 2014 when Iraq’s top cleric Ali Sistani rallied hundreds of thousands of Shiite volunteers to fight the Sunni-dominated Islamic State — also an enemy of the U.S. — when its forces reached Baghdad’s gates.

Out of those groups grew the Popular Mobilization Units, a collection of Shiite-dominated militias that stalled — with Iranian assistance — the extremists’ rampage. Tehran later helped formalize the militias into an official branch of Iraq’s armed forces.

A massive U.S. Army study of the Iraq war released last year declared that “an emboldened and expansionist Iran appears to be the only victor” of the nearly 17-year, nearly $1-trillion U.S. effort, which led to the loss of thousands of American lives and hundreds of thousands of Iraqi lives.

The attack Friday leaves the U.S., or those with mildly pro-U.S. views, with even less room to maneuver.

“Politicians who wanted a neutral approach are in a difficult position, because the U.S. has carried out assassinations on Iraq’s territory without approval, without authority,” said Sajad Jiyad, director of the Baghdad-based Bayan Center think tank, in a phone interview Saturday.

Though Muhandis was a longtime U.S. adversary, Jiyad said, the killing, in the eyes of many politicians, was an attack on one of the arms of Iraq’s security forces — a point Abdul Mahdi, the prime minister, emphasized in a statement Friday.

“Assassinating an Iraqi military leader with an official position is an aggression on Iraq,” he said, adding that the two slain leaders — Abdul Mahdi dubbed them “martyrs”— were important “symbols in achieving victory” over Islamic State.

“If Iraq is forced to choose between the two sides, more logically it’s the Iranians that would be the choice: They’ll always be there; the Americans won’t,” Jiyad said. “The problem is no one wanted to make that choice.”

Well before the airstrike ordered by Trump, relations between Washington and Baghdad had been souring.

There was the misstep of the president’s visit to Asad Air Base in December 2018, when he met with U.S. troops for three hours but left without meeting any Iraqi officials.

Another snub came when the U.S. failed to extend an invitation to Iraq’s leaders for a White House visit, the first time that has happened since 2003. Earlier this year, U.S. officials all but forced the government to divide lucrative power generation contracts between Siemens, the giant German corporation billed as the favorite, and General Electric.

The impression among the political class, said Ali Taher, an analyst at the Bayan Center, is that “the U.S. is not to be trusted.”

At the heart of U.S.-Iraqi relations is the future status of the remaining 5,000 or so American soldiers and the unspecified number of contractors in the country. Their continued presence, a topic of perennial contention in Iraq’s fractious parliament that is set to be discussed in an emergency session Sunday, may be the first fallout of the attack, even as Washington moves to station additional troops in the region.

In the immediate aftermath, Iraqi politicians had already begun to agitate for a repeal of the countries’ military arrangement, which consists of a train-and-assist capacity and was instrumental in taking back territories overrun by Islamic State.

The airstrike Friday, Abdul Mahdi said, was “a blatant violation of the conditions for the U.S. forces’ presence in Iraq.”

He called for the parliament session to “take the appropriate legislative decisions and necessary procedures to preserve the dignity, security and sovereignty of Iraq.”

The Trump administration does not publicly acknowledge the depth of anti-American sentiment, saying many Iraqis side with the United States but are pressured to voice support for Iran by its proxies. Robert O’Brien, Trump’s national security advisor, said the White House would be “disappointed” if Iraq votes to boot the Americans after the U.S. has invested “enormous amounts of blood and treasure” in the country.

“We’re working with our allies on the ground to prevent [being voted out] from happening,” said a senior State Department official, briefing reporters in Washington on condition of anonymity in keeping with administration protocols. “We are a positive presence in Iraq, but not for Iran. They view us as a threat.

“The government of Iraq right now is faced with a choice whether they want to be an Iranian satellite state or whether they want to be a sovereign nation state of good standing in the international community,” the official said. “We would help them move toward the latter.”

A more immediate effect has been the reduction of the U.S.’ cooperation with Iraq in fighting the remnants of Islamic State, with reports that the U.S.-led coalition had scaled back operations against the extremists, while also cutting back on its training duties with Iraqi forces.

But even if Iraqi politicians believe they need the U.S., there’s little chance they would rise to its defense, said Renad Mansour, a research fellow at the London-based Chatham House think tank.

“There have been several instances where if an Iraqi politician sided with Washington it would mean the end of their career,” Mansour said in a phone interview on Saturday.

He cited the example of Haider Abadi, who was Iraq’s prime minister until 2018. He lost his reelection bid despite strong support from Washington.

In any case, Mansour added, politicians have learned that success is more likely with Iran as a friend.

“Many Iraqi politicians have realized that the U.S. is not a reliable ally,” Mansour said.

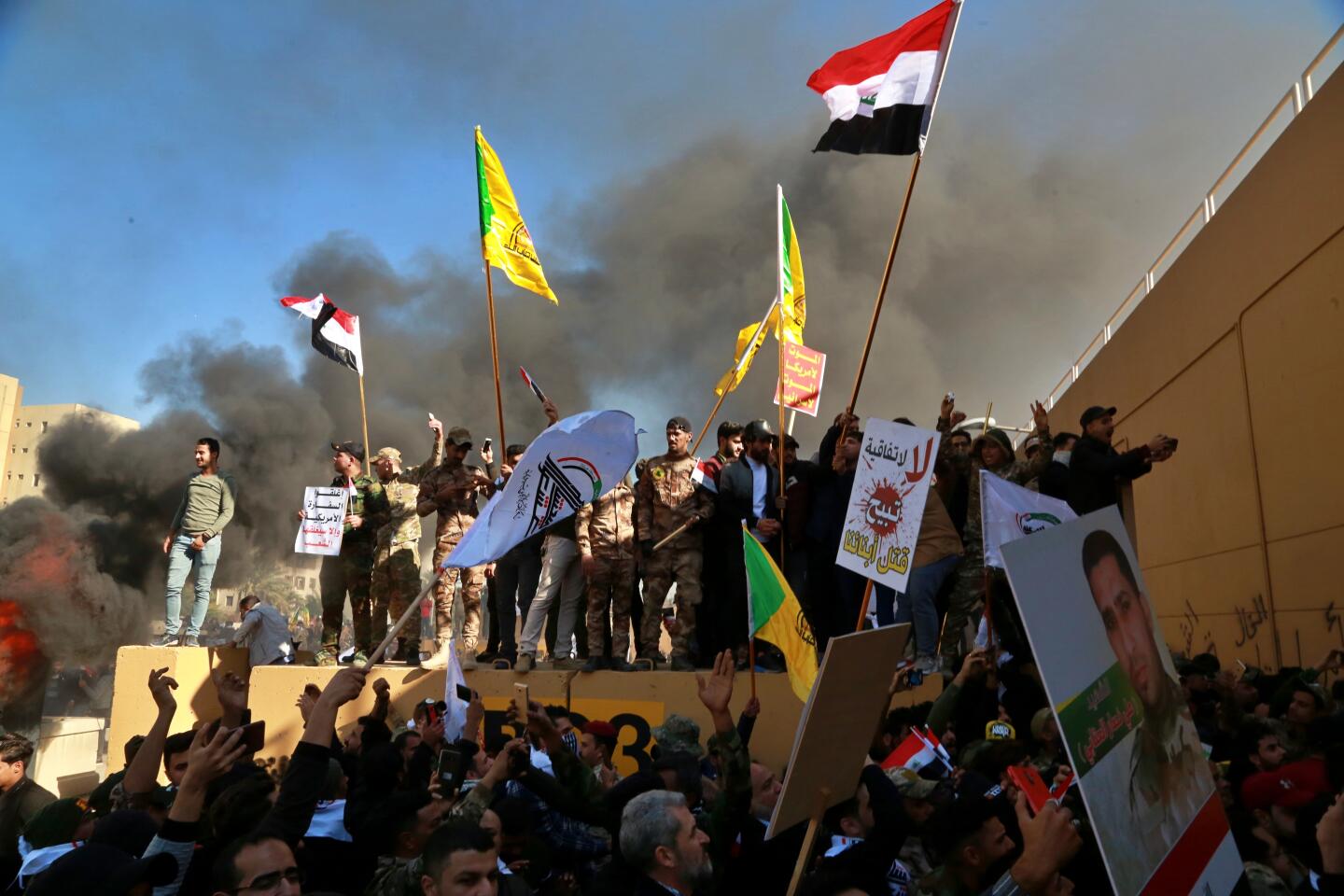

Saturday evening brought another sign of the anger now facing the Americans. Just hours after the funeral procession, sirens blared near the U.S. Embassy and rockets landed near two Iraqi bases that host coalition forces in Baghdad and Balad, the American military said.

They were the same type of attacks that killed a U.S. contractor Dec. 27, which the White House says spurred its actions in the first place. There were no immediate reports of casualties.

Times staff writer Tracy Wilkinson in Washington contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.