They came here after the U.S. irradiated their islands. Now they face an uncertain future

SPOKANE, Wash. — They come from a low-lying Pacific island nation synonymous with U.S. nuclear weapons testing during the Cold War. In part because of that troubled history, one-third of the Marshall Islands’ population — roughly 27,000 and growing — now reside in the United States, where their future is uncertain.

Under a 1986 bilateral agreement, the Marshallese people were permitted to enter the United States as “legal non-immigrants” in return for the U.S. military continuing to operate a weapons testing base in the Marshalls. Many islanders found jobs in meat processing plants in Arkansas, canneries in Oregon and various service industries in Washington state, including in Spokane, where church groups and family helped build a community providing newcomers with employment, homes, education and healthcare.

Now, amid tensions caused by lingering radiation and sea-level rise in the Marshall Islands, it is uncertain whether a new Marshallese government will renew a compact with the United States that has tied the two countries together for 33 years. If a new government decides to break that compact, the 27,000 Marshallese in the U.S. will lose their legal status and perhaps be forced to return to an island nation racked by poverty, disease and rising sea levels.

China also has been seeking to increase its influence in the Marshall Islands, where the results of a recent election could complicate the U.S. presence in the Pacific and the fate of Marshallese here.

“It’d be a tragedy if our parliament decides to break from the United States,” said Doresty Daniel, who came to Spokane two years ago, by way of Hawaii. “What the United States did in the Marshall Islands is a tragedy. But, what’s the alternative? Do we really think China is going to treat us better?”

Many Marshallese expats hope the two sides will patch up their differences, allowing them to stay. But the situation is more unsettled than many have seen in their lifetimes.

In Spokane, thousands of islanders have made the city their home. After English, Marshallese is the second-most spoken language in the school system.

Some of the youngsters were sent here alone — staying with siblings, cousins, aunts, uncles and friends — to get an education unavailable back home.

On a recent December day, as freezing rain fell outside Spokane’s inner-city Lewis and Clark High School, washing away the graying, sooty snow, a room of Marshallese teens laughed while explaining their familial relationships to a visitor.

“He’s my brother,” said Atina Jabuwe, 17, pointing to a 17-year-old boy sitting across from her in a small circle of seven students in Shannon Brown’s English language development classroom.

“And so is he,” she said, motioning to another 17-year-old boy in the circle before turning to three young women, whom she said described as her two sisters and “auntie.”

“Well, not my sister-sister or brother-brother,” she said as the group laughed. “They’re what you would call cousins. But, she,” she said, pointing to another young woman in the circle, “is really, truly our auntie.”

With climate change and rising seas, the U.S. is about to face a reckoning for the toxic nuclear legacy we buried — and forgot — in the Marshall Islands.

A string of coral atolls sitting roughly 5,000 miles southwest of Los Angeles, the Marshall Islands was the site of 67 U.S. nuclear weapons tests between 1946 and 1958, which obliterated whole islands and exposed thousands of Marshallese to radiation. With an average elevation of seven feet, it is increasingly vulnerable to the scourges of climate change — oppressive heat, bleached reefs and flooding.

“I got into a debate with a friend about that,” Atina said.”Are the islands shrinking or sinking? I say shrinking because the water is moving up. But she said sinking, because they are going under.”

Unemployment is estimated at about 36%, and recently the islands have been battered by a record outbreak of dengue fever.

Although the Marshallese in Spokane aren’t dealing with these issues directly, they are acutely aware, and worried.

Daniel, for instance, described the island she grew up on in Mili Atoll. “The beach where I played, and the coconut trees I climbed and played under, they are gone. It’s just water.”

Some students also struggle with the shared history of the two nations, which, as is the case nationwide, is not part of the Spokane schools’ curriculum.

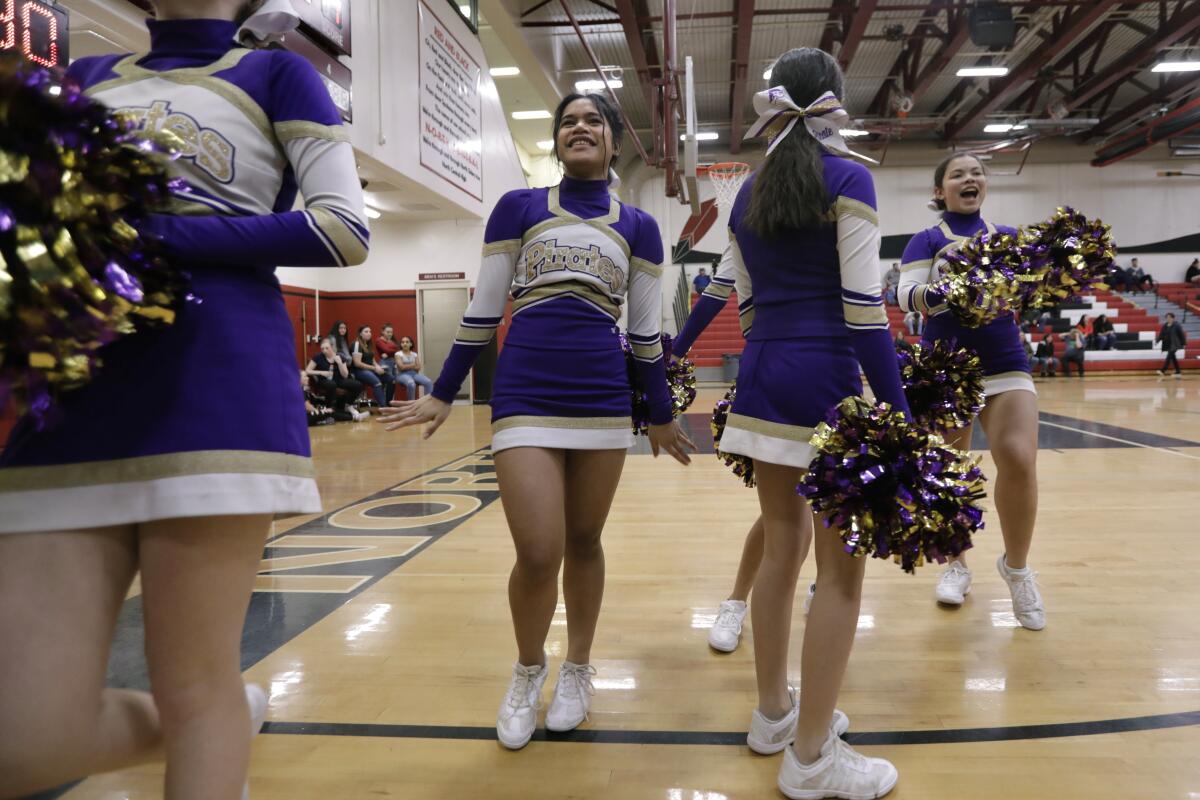

“I heard about what the Americans did to us,” said Telirose Thomas, 18, a senior and cheerleader at nearby Rogers High School. “It’s hard to imagine they did such a thing. It’s seems so, well, un-American.”

But she intends to return, as do most Marshallese — even the younger ones who have grown up here.

“My parents work really hard, and they say someday they will go back,” said Thomas, who arrived in 2013 and hopes to eventually become a neurosurgeon.

“But I want to be a doctor in the Marshall Islands. I want to be a doctor there because they don’t really have any,” she said.

****

Since 1986, the Republic of the Marshall Islands has enjoyed a special relationship with the United States — one that allows its residents to live, work and study in the United States without visas.

Marshallese are not considered immigrants or refugees, nor are they considered U.S. citizens. Along with people from the Federated States of Micronesia and Palau — collectively known as freely associated nations — they pay taxes, can serve in the U.S. armed forces and enjoy freedom of movement throughout the 50 states.

They are also denied basic social services through Medicare, Social Security or specialized federal programs designed to help refugees and immigrants — benefits that were lost in 1996 when President Clinton signed a sweeping welfare reform law.

States such as Washington and Oregon now have programs designed to fill this gap. This was largely the result of determined Micronesians, Palauans and Marshallese, such as Spokane’s Rick and Rose Kabua, who worked with Washington state legislators to ensure that Marshallese were provided essential services.

“Those benefits were meant for us,” said Rick Kabua, who is descended from Marshallese royalty, the son of the Kwajalein Atoll’s king, or Iroijlaplap. He works in the Spokane school system as a cultural liaison for Marshallese students.

As a result of his work and an organization known as the Compact of Free Association Alliance National Network, the Pacific Northwest has become a major destination for Marshallese. They have only limited access to healthcare in their home nation, which, despite a historical legacy of radiation-induced cancers, has no oncologists.

Other Marshallese centers — such as Springdale, Ark.; Costa Mesa; Enid, Okla.; and most of Hawaii — don’t have the healthcare benefits provided by Washington and Oregon.

But politics in the Marshall Islands threatens to upend it all.

Many island-living Marshallese feel the United States has betrayed their trust and failed to provide just compensation for the upheaval caused by U.S. nuclear testing.

Congress is demanding the Department of Energy investigate an aging, cracking U.S. nuclear waste dump in the Marshall Islands, the focus of a Los Angeles Times investigation this year.

The Republic of the Marshall Islands for decades has become dependent on U.S. aid and financing — accounting for roughly 36% of the nation’s expenditures. But more recently, China has been making overtures across the Pacific, successfully courting many island nations with promises for financing and funding.

It’s part of China’s Belt and Road development initiative, which is designed to expand Beijing’s political and military reach. And it poses a strategic military risk for the United States, which has military bases through the Pacific, including a major missile testing site in the Marshall Islands, on Kwajalein Atoll.

“Kwajalein is of central importance for the U.S.,” said Jeffrey Lewis, director of the East Asia Nonproliferation Program at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies in Monterey, Calif. “It’s the hub of missile testing in the Pacific.”

“At some point, you have to ask who is going to help,” said James Matayoshi, the mayor of Rongelap Atoll, in a September interview.

Rongelap is one of the 29 atolls that make up the Marshall Islands. Matayoshi has drafted plans that, with Chinese venture funding, would turn his atoll into a central Pacific tech hub.

On Nov. 18, the Marshallese went to the polls to cast their lot. And for the first time, the elections excluded those living abroad — denying the 27,000 Marshallese in the United States a vote. Although the Marshall Islands Supreme Court has pronounced that exclusion unconstitutional, its ruling came too late for this latest election.

The new government is set to assemble Jan. 6, so results are expected any day. The uncertainty has left many Marshallese in Spokane and throughout the United States anxious.

“We’re justifiably worried,” said Pastor Humphrey Jonathan, minister of the Assembly of God church in Spokane, one of roughly a dozen Marshallese churches in the region.

That’s because if a Chinese-leaning Marshallese government were to break from the compact before it expires in 2023, the rights and privileges of the Marshallese living in the United States would be withdrawn, said Howard Hills, a Laguna Beach-based lawyer who helped write the first agreement.

“If one of the two parties decide to withdraw from the compact, it becomes null and void. Everything — all those rights — disappear,” he said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.