A Christmas of grief nearly five years after Arizona woman’s death in Islamic State captivity

PRESCOTT, Ariz. — At Christmastime five years ago, Carl and Marsha Mueller did what they always did when their 26-year-old daughter Kayla was out in the world somewhere: They laid a place for her at the holiday table.

Outside their home in Prescott, Ariz., the mountain air was winter chill, but inside, the lights glowed warm. The tree was trimmed with ornaments, many of them depicting owls, Kayla’s favorite.

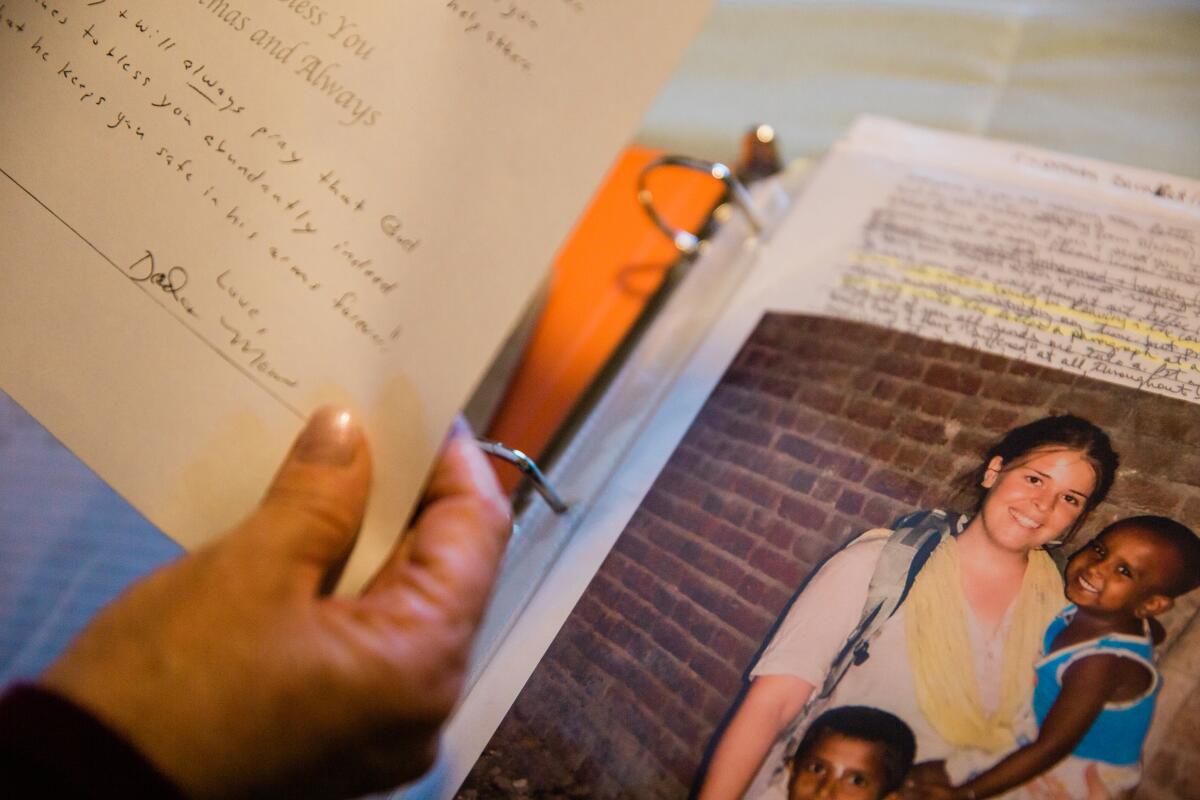

The Muellers didn’t know it then, but the 2014 holiday season would be the last Christmas they could harbor any real hope that their daughter — a laughing little girl who grew into a compassionate young woman, one whose humanitarian interests took her from India to Israel — was still alive.

Today, Carl and Marsha Mueller, both of them 67 and retired — he from the auto-body shop he owned; she from nursing — remain consumed with the search for answers. Seated side by side on their sofa, they recount a years-long odyssey of sorrow and confusion, one that has taken them from their Arizona hometown to as far away as Iraqi Kurdistan.

On that Christmas, though, they had no idea of the ordeal that would lie ahead. Kayla, who traveled to southern Turkey to work with Syrian refugees, had been taken captive 16 months earlier, in Aleppo, Syria, after leaving a medical compound run by the humanitarian group Doctors Without Borders.

Soon after, her family learned she was being held by Islamic State, the brutal fundamentalist group that would go on to impose a medieval reign of terror over large swaths of Syria and Iraq.

By the late summer of 2014, her captors had killed several of her fellow U.S. hostages — horrific beheadings staged against a bleak desert backdrop, with videos gleefully posted online by the group. But Kayla, whose plight was then a closely held secret, was still alive, and her parents said in the early winter of that year, U.S. authorities told them there was no intelligence suggesting she had been harmed in captivity.

The Muellers would find out only later, they said, the degree to which their daughter was being brutalized during that period. Some of the worst abuse came directly at the hands of Abu Bakr Baghdadi, Islamic State’s self-proclaimed caliph, who died in a U.S. raid in October.

Less than two months after that Christmas five years ago, the Muellers learned — via an Islamic State-linked Twitter account, with later confirmation from U.S. officials — that Kayla was dead. The group said she was killed in a Jordanian airstrike, a story her parents now doubt.

They still do not know exactly how their daughter died, or whether there might even be some infinitesimal hope of her survival. But they say that with the help of former FBI agent Ali Soufan, who now runs a private security group, new information has continued to emerge. That includes indications that Baghdadi, in whose household she was held for a time, may have personally ordered Kayla’s death.

The Muellers still hope they will someday have final proof of her fate. That their daughter’s remains will eventually be recovered and repatriated. That there will be a graveside at which to grieve.

There can never be closure for them, not in any real sense. What they have learned of Kayla’s time in captivity would be unbearably painful for any parent to contemplate. When her father says the word “raped,” his voice sounds like fabric tearing.

Yet they revisit these events, even speak of them to strangers, because they believe it helps keep their daughter’s memory alive. And through it all, they have held one abiding wish — although its meaning has changed over time.

“We just want to bring Kayla home,” Marsha Mueller said.

--

The Syrian city of Raqqa, on the banks of the Euphrates, is where the nascent Islamic State group first displayed the audacious scope of its ambition. In 2013, in the self-declared capital of what the group would come to call its caliphate, the militants began setting up a judicial system based on their harsh interpretation of Islamic law, fashioned a working bureaucracy and commandeered infrastructure to create a quasi-state, while looking outward to expand their territory.

When Kayla was taken in Aleppo in August 2013, just days before her 25th birthday, large tracts of Syria’s north had already fallen to rebels fighting against the rule of President Bashar Assad. Dozens of factions, including extremist groups, competed for weapons and for sources of revenue — including foreign captives they could ransom back to their home countries.

It’s unclear which militants seized her, but her capture coincided with Islamic State’s push into the shadowlands of eastern Syria. By the spring of 2014 she, together with other Western hostages, was being held by the group in a derelict oil refinery south of Raqqa, according to subsequent witness accounts.

By late May of that year, the Muellers were in direct contact with Islamic State by email. The family wanted proof of life; the militants replied by telling them to pose personal questions to which only Kayla would know the correct response.

At an age when most kids are preoccupied with friends and school, Kayla Jean Mueller devoted herself to helping those in need around the world.

One of the queries her parents came up with was the missing word in an aphorism that she used to repeat to her little niece. The phrase in question was “Music is…” and the right answer came back: “Everywhere.” They knew then that she was still alive.

The militants, who by then were successfully extracting ransoms for some European hostages, threatened Kayla with death and demanded a multi-million-dollar payoff. U.S. government policy at the time, since eased, left families of hostages held overseas vulnerable to prosecution if they made a payment to a terror group.

Around that same time, the late spring of 2014, the U.S. Joint Special Operations Command sought permission from the Obama administration to carry out a raid inside Syria to try to free the hostages. Carl Mueller remains deeply embittered by the fact that the rescue attempt did not take place until July, missing the captives by days, and that the family was not told of the operation until afterward, when word of it filtered out in news reports.

“That’s the way they treated us,” he said, his voice rising in anger.

Both the Muellers called that part of a pattern of misinformation and arms-length treatment by the Obama administration, which said at the time it was doing all it could for the hostages.

On Aug. 14, 2014, after little more than a year in captivity, Kayla turned 26. Five days later, a grisly video, apparently shot outside Raqqa and circulated online, showing the beheading of journalist James Foley by a knife-wielding militant dubbed Jihadi John. Other executions of captive Americans followed: journalist Steven Sotloff and aid worker Peter Kassig, also known as Abdul-Rahman Kassig.

In despair, the Muellers in September addressed a video appeal directly to Islamic State’s leader, Baghdadi. “I am coming to you with a mother’s heart, for the love of her daughter,” Marsha Mueller told him.

It was to no avail. In February 2015, three days after the militants carried out yet another gruesome execution in Raqqa — this time, of a captured Jordanian fighter pilot who was burned alive in a cage — Islamic State said Kayla had been killed in a Jordanian airstrike.

Her body was never recovered, but U.S. officials confirmed her death on Feb. 10, 2015. President Obama conveyed “deepest condolences” and vowed to bring those responsible for her captivity, and ultimately her death, to justice.

--

The U.S. raid that resulted in the death of Baghdadi, announced by President Trump on Oct. 27 of this year, brought the Muellers some measure of comfort. They were touched that the military operation was dedicated to Kayla, and a lengthy personal phone call from Trump moved them to tears, they said.

But frustration lingers, as do mysteries. The Islamic State leader blew himself up as U.S. special forces closed in; had he instead been captured, Marsha Muelller said wistfully, he might have revealed something.

His reign was marked with bouts of genocidal reengineering of communities that didn’t fit his vision for a Sunni Muslim state.

Still, there are living witnesses to the months immediately preceding Kayla’s death, and Soufan, the former FBI agent who has become a close family friend, is actively pursuing leads.

One harrowing new piece of the puzzle came from an interview conducted by him with Nisreen Assad Ibrahim Bahar, known as Umm Sayyaf, the widow of senior Baghdadi associate Abu Sayyaf. She said her late husband told her that Baghdadi himself ordered Kayla killed, perhaps because her knowledge represented a security threat to the group. U.S. authorities charged Umm Sayyaf in 2016 in connection with Kayla’s death, and said she was aware that Baghdadi repeatedly raped her.

The Muellers have met, also, with women and girls who were held alongside their daughter at one point or another, accounts they describe as both a bane and a balm. The ex-captives, including two Yazidi girls and two Western women who worked for Doctors Without Borders, told wrenching stories of suffering, but also described Kayla’s quiet determination to comfort fellow prisoners.

“Even I never knew she was so strong,” her mother said.

The couple finds something akin to consolation at a playground in Prescott that opened in 2016, dedicated to Kayla’s memory. On a cold sunny morning last week, they took visitors there, pointing out the zipline, the special swing designed to safely cradle disabled children.

Carl Mueller often comes alone, his wife said. She likes to visit with Kayla’s niece, who is now nearly 8. Occasionally, Marsha Mueller said, she slips and calls the little girl by her daughter’s name.

“Kayla saw people as precious, and saw life as precious,” she said. “That’s what we hope people will remember about her. That’s who she was.”

King reported from Prescott, Ariz., and Bulos from Amman, Jordan.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.