Secret documents reveal how China mass detention camps work

The watch towers, double-locked doors and video surveillance in the Chinese camps are there “to prevent escapes.” Uighurs and other minorities held inside are scored on how well they speak the dominant Mandarin language and follow strict rules on everything down to bathing and using the toilet, scores that determine if they can leave.

“Manner education” is mandatory, but “vocational skills improvement” is offered only after a year in the camps.

Voluntary job training is the reason the Chinese government has given for detaining more than a million ethnic minorities, most of them Muslims. But a classified blueprint leaked to a consortium of news organizations shows the camps are instead precisely what former detainees have described: forced ideological and behavioral re-education centers run in secret.

The classified documents lay out the Chinese government’s deliberate strategy to lock up ethnic minorities even before they commit a crime, to rewire their thoughts and the language they speak.

The papers also show how Beijing is pioneering a new form of social control using data and artificial intelligence. Drawing on data collected by mass surveillance technology, computers issued the names of tens of thousands of people for interrogation or detention in just one week.

Taken as a whole, the documents give the most significant description yet of high-tech mass detention in the 21st century in the words of the Chinese government itself. Experts say they spell out a vast system that targets, surveils and grades entire ethnicities to forcibly assimilate and subdue them — especially Uighurs, a predominantly Muslim Turkic minority of more than 10 million people with their own language and culture.

“They confirm that this is a form of cultural genocide,” said Adrian Zenz, a leading security expert on the far western region of Xinjiang, the Uighur homeland. “It really shows that, from the onset, the Chinese government had a plan.”

Zenz said the documents echoed the aim of the camps as outlined in a 2017 report from a local branch of the Xinjiang Ministry of Justice: to “wash brains, cleanse hearts, support the right, remove the wrong.”

China has struggled for decades to control Xinjiang, where the Uighurs have long resented Beijing’s heavy-handed rule. After the 9/11 attacks in the United States, Chinese officials began justifying harsh security measures and religious restrictions as necessary to fend off terrorism, arguing that young Uighurs were susceptible to the influence of Islamic extremism. Hundreds have died since in terror attacks, reprisals and race riots, both Uighurs and Han Chinese.

In 2014, Chinese President Xi Jinping launched what he called a “People’s War on Terror” when bombs set off by Uighur militants tore through a train station in Urumqi, the capital of Xinjiang, just hours after he concluded his first state visit there.

“Build steel walls and iron fortresses. Set up nets above and snares below,” state media cited Xi as saying. “Cracking down severely on violent terrorist activities must be the focus of our current struggle.”

In 2016, the crackdown intensified dramatically after Xi named Chen Quanguo, a hardline official transferred from Tibet, as Xinjiang’s new head. Most of the documents were issued in 2017, as Xinjiang’s “War on Terror” morphed into an extraordinary mass detention campaign using military-style technology.

The practices largely continue today. The Chinese government says they work.

“Since the measures have been taken, there’s no single terrorist incident in the past three years,” said a written response from the Chinese Embassy in the United Kingdom. “Xinjiang is much safer.... The so-called leaked documents are fabrication and fake news.”

The statement said religious freedom and the personal freedom of detainees was “fully respected” in Xinjiang.

The documents were given to the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists by an anonymous source. The ICIJ verified them by examining state media reports and public notices from the time, consulting experts, cross-checking signatures and confirming the contents with former camp employees and detainees.

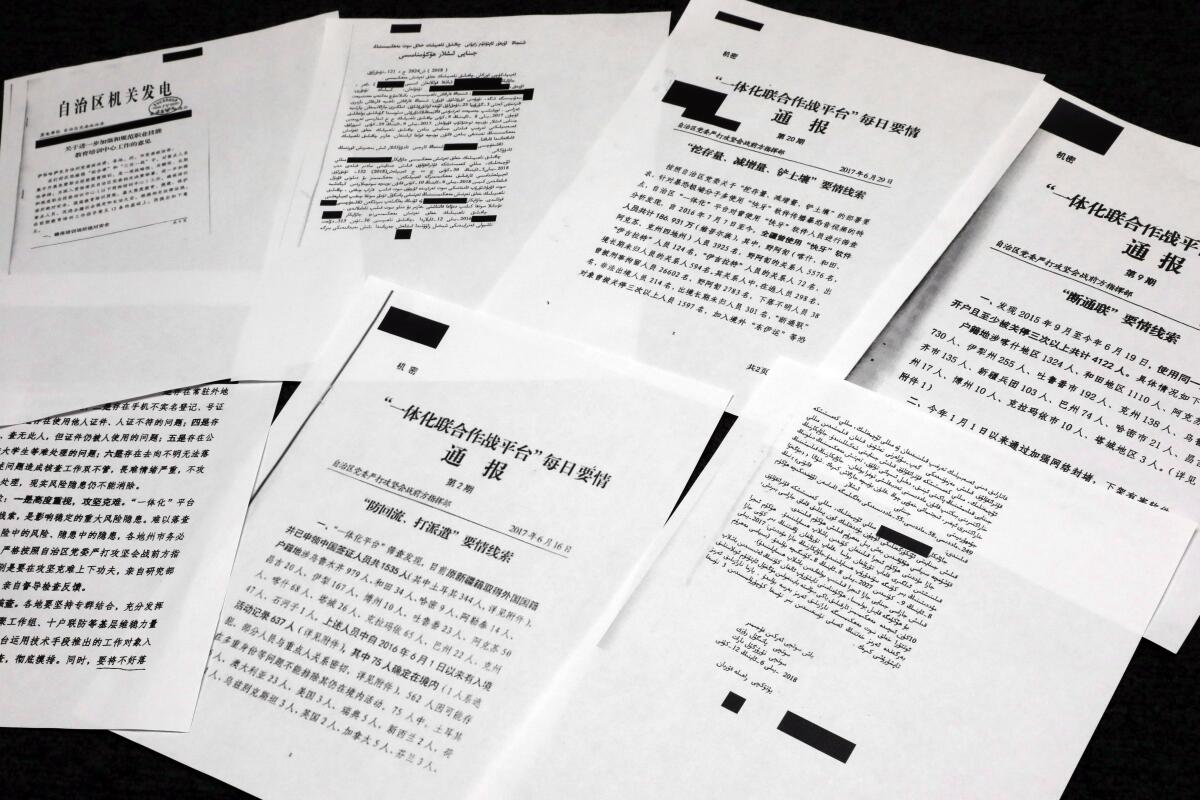

They consist of a notice with guidelines for the camps, four bulletins on how to use technology to target people, and a court case sentencing a Uighur Communist Party member to 10 years in prison for telling colleagues not to say dirty words, watch porn or eat without praying.

The documents were issued to rank-and-file officials by the powerful Xinjiang Communist Party Political and Legal Affairs Commission, the region’s top authority overseeing police, courts and state security. They were put out under the head official at the time, Zhu Hailun, who annotated and signed some personally.

The documents confirm from the government itself what is known about the camps from the testimony of dozens of Uighurs and Kazakhs, satellite imagery and tightly monitored visits by journalists to the region.

Erzhan Qurban, an ethnic Kazakh who moved back to Kazakhstan, was grabbed by police on a trip back to China to see his mother and accused of committing crimes abroad. He protested that he was a simple herder who had done nothing wrong. But for the authorities, his time in Kazakhstan was reason enough for detention.

Qurban told the Associated Press he was locked in a cell with 10 others last year and told not to engage in “religious activities” like praying. They were forced to sit on plastic stools in rigid postures for hours at a time. Talk was forbidden, and two guards kept watch 24 hours a day. Inspectors checked that nails were short and faces trimmed of mustaches and beards, traditionally worn by pious Muslims.

Those who disobeyed were forced to squat or spend 24 hours in solitary confinement in a frigid room.

“It wasn’t education; it was just punishment,” said Qurban, who was held for nine months. “I was treated like an animal.”

Who gets rounded up and how

On Feb. 18, 2017, Zhu, the Han Chinese official who signed the documents, stood in chilly winter weather atop the front steps of the capital’s city hall, overlooking thousands of police in black brandishing rifles.

“With the powerful fist of the People’s Democratic Dictatorship, all separatist activities and all terrorists shall be smashed to pieces,” Zhu announced into a microphone.

With that began a new chapter in the state’s crackdown. Police called Uighurs and knocked on their doors at night to take them in for questioning. Others were stopped at borders or arrested at airports.

In the years since, as Uighurs and Kazakhs were sent to the camps in droves, the government built hundreds of schools and orphanages to house and re-educate their children. Many of those who have fled into exile don’t even know where their children or loved ones are.

The documents make clear that many of those detained have not actually done anything. One document explicitly states that the purpose of the pervasive digital surveillance is “to prevent problems before they happen” — in other words, to calculate who might rebel and detain them before they have a chance.

This is done through a system called the Integrated Joint Operations Platform, designed to screen entire populations. Built by a state-owned military contractor, the IJOP began as an intelligence-sharing tool developed after Chinese military theorists studied the U.S. Army’s use of information technology in Iraq and Afghanistan.

“There’s no other place in the world where a computer can send you to an internment camp,” said Rian Thum, a Xinjiang expert at the University of Nottingham. “This is absolutely unprecedented.”

The IJOP spat out the names of people considered suspicious, such as thousands of “unauthorized” imams not registered with the Chinese government, along with their associates. Suspicious or extremist behavior was so broadly defined that it included going abroad, asking others to pray or using cellphone apps that cannot be monitored by the government.

The IJOP zoomed in on users of “Kuai Ya,” a mobile application similar to the iPhone’s Airdrop, which had become popular in Xinjiang because it allows people to exchange videos and messages privately. One bulletin showed that officials identified more than 40,000 “Kuai Ya” users for investigation and potential detention; of those, 32 were listed as belonging to “terrorist organizations.”

“They’re scared people will spread religion through ‘Kuai Ya,’ ” said a man detained after police accused him of using the app. He spoke to AP on condition of anonymity to protect himself and his family. “They can’t regulate it.... So they want to arrest everyone who’s used ‘Kuai Ya’ before.”

The system also targeted people who obtained foreign passports or visas, reflecting the government’s fear of Islamic extremist influences from abroad and deep discomfort with any connection between the Uighurs and the outside world. Officials were asked to verify the identities even of people outside the country, showing how China is casting its dragnet for Uighurs far beyond Xinjiang.

In recent years, Beijing has put pressure on countries to which Uighurs have fled, such as Thailand and Afghanistan, to send them back to China. In other countries, state security has also contacted Uighurs and pushed them to spy on each other. For example, a restaurateur now in Turkey, Qurbanjan Nurmemet, said police contacted him with videos of his son strapped to a chair and asked him for information on other Uighurs in Turkey.

Despite the Chinese government’s insistence that the camps are vocational training centers for the poor and uneducated, the documents show that those rounded up include party officials and university students.

After the names were collected, lists of targeted people were passed to prefecture governments, who forwarded them to district heads, then local police stations, neighbor watchmen, and Communist Party cadres living with Uighur families.

Some former detainees recalled being summoned by officers and told their names were listed for detention. From there, people were funneled into different parts of the system, from house arrest to detention centers with three levels of monitoring to, at its most extreme, prison.

Experts say the detentions are a clear violation of China’s own laws and constitution. Maggie Lewis, a professor of Chinese law at Seton Hall University, says the Communist Party is circumventing the Chinese legal system in Xinjiang.

“Once you’re stamped as an enemy, the gloves go off,” she said. “They’re not even trying to justify this legally....This is arbitrary.”

The detention campaign is sweeping. A bulletin notes that in a single week in June 2017, the IJOP identified 24,612 “suspicious persons” in southern Xinjiang, with 15,683 sent to “education and training,” 706 to prison and 2,096 to house arrest. It is unknown how typical this week might be. Local officials claim far fewer than a million are in “training,” but researchers estimate that up to 1.8 million have been detained at one point or another.

The bulletins stress that relationships must be scrutinized closely, with those interrogated pushed to report the names of friends and relatives. Mamattursun Omar, a Uighur chef arrested after working in Egypt, was interrogated in four detention facilities over nine months in 2017. Omar told the AP that police asked him to verify the identities of other Uighurs in Egypt.

Eventually, Omar says, they began torturing him to make him confess that Uighur students had gone to Egypt to take part in jihad. They strapped him to a contraption called a “tiger chair,” shocked him with electric batons, beat him with pipes and whipped him with computer cords.

“I couldn’t take it anymore,” Omar said. “I just told them what they wanted me to say.”

Omar gave the names of six others who worked at a restaurant with him in Egypt. All were sent to prison.

What happens inside the camps

The documents also detail what happens after someone is sent to an “education and training center.”

Publicly, in a recent white paper, China’s State Council said “the personal freedom of trainees at the education and training centers is protected in accordance with the law.” But internally, the documents describe facilities with police stations at the front gates, high guard towers, one-button alarms and video surveillance with no blind spots.

Detainees are only allowed to leave if absolutely necessary, for example because of illness, and even so must have somebody “specially accompany, monitor and control” them. Bath time and toilet breaks are strictly managed and controlled “to prevent escapes.” And cellphones are strictly forbidden to stop “collusion between inside and outside.”

“Escape was impossible,” said Kazakh kingergarten administrator Sayragul Sauytbay, a Communist Party member who was abducted by police in October 2017 and forced to become a Mandarin camp instructor. “In every corner in every place there were armed police.”

Sauytbay called the detention center a “concentration camp ... much more horrifying than prison,” with rape, brainwashing and torture in a “black room” where people screamed. She and another former prisoner, Zaomure Duwati, also told the ICIJ that detainees were given medication that made them listless and obedient, and every move was surveilled.

AP journalists who visited Xinjiang in December 2018 saw patrol towers and high walls lined with green barbed wire fencing around camps. One camp in Artux, just north of Kashgar, sat in the middle of a vast, empty, rocky field and appeared to include a police station at the entrance, workshops, a hospital and dormitories, one with a sign reading “House of Workers” in Chinese.

Recent satellite imagery shows that guard towers and fencing have been removed from some facilities, suggesting the region may have been softening restrictions in response to global criticism. Shohrat Zakir, the governor of Xinjiang, said in March that those detained could now request time to go home on weekends, a claim the AP could not independently verify.

The first item listed as part of the curriculum is ideological education, a bold attempt to change how detainees think and act. It is partly rooted in the ancient Chinese belief in transformation through education — taken, before, to terrifying extremes during the mass thought reform campaigns of Mao Tse-tung.

“It’s the dark days of the Cultural Revolution, except now it’s powered by high-tech,” said Zenz, the researcher.

By showing students the error of their former ways, the centers are supposed to promote “repentance and confession,” the directive said. For example, Qurban, the Kazakh herder, was handcuffed, brought to an interview with a Han Chinese leader and forced to acknowledge that he regretted visiting abroad.

The indoctrination goes along with what is called “manner education,” where behavior is dictated down to ensuring “timely haircuts and shaves,” “regular change of clothes” and “bathing once or twice a week.” The tone, experts say, echoes a general perception by the Han Chinese government that Uighurs are prone to violence and need to be civilized — in much the same way white colonialists treated indigenous people in the U.S., Canada and Australia.

“It’s a similar kind of savior mentality — that these poor Uighurs didn’t understand that they were being led astray by extremists,” said Darren Byler, a scholar of Uighur culture at the University of Washington. “The way they think about Uighurs in general is that they are backward, that they’re not educated ... [that] these people are unhygienic and need to be taught how to clean themselves.”

Students are to be allowed a phone conversation with relatives at least once a week, and can meet them via video at least once a month, the documents say. Trainers are told to pay attention to “the ideological problems and emotional changes that arise after family communications.”

Mandarin is mandated. Beijing has said “the customs of all ethnic groups and the right to use their spoken and written languages are fully protected at the centers.” But the documents show that, in practice, lessons are taught in Mandarin, and it is the language to be used in daily communication.

A former staffer at Xinjiang TV now in Europe was also selected to become a Mandarin teacher during his monthlong detention in 2017. Twice a day, detainees were lined up and inspected by police, and a few were questioned in Mandarin at random, he said. Those who couldn’t respond in Mandarin were beaten or deprived of food for days. Otherwise, speaking was forbidden.

One day, the former teacher recalled, an officer asked an old farmer in Mandarin whether he liked the detention center. The man apologized in broken Mandarin and Uighur, saying it was hard for him to understand because of his age. The officer strode over and struck the old man’s head with a baton. He crumpled to the ground, bleeding.

“They didn’t see us as humans,” said the former teacher, who declined to provide his name out of fear of retribution against his family. “They treated us like animals — like pigs, cows, sheep.”

Detainees are tested on Mandarin, ideology and discipline, with “one small test per week, one medium test per month, and one big test per season,” the documents state. These test scores feed into an elaborate point system.

Detainees who do well are to be rewarded with perks like family visits, and may be allowed to “graduate” and leave. Detainees who do poorly are to be sent to a stricter “management area” with longer detention times. Former detainees told the Associated Press that punishments included food deprivation, handcuffing, solitary confinement, beatings and torture.

Detainees’ scores are entered in the IJOP. Students are sent to separate facilities for “intensive skills training” only after at least one year of learning ideology, law and Mandarin.

After they leave, the documents stipulate, every effort should be made to get them jobs. Some detainees describe being forced to sign job contracts, working long hours for low pay and barred from leaving factory grounds during weekdays.

Qurban, the Kazakh herder, said after nine months in the camp, a supervisor came to tell him he was “forgiven” but must never tell what he had seen. After he returned to his village, officials told him he had to work in a factory.

“If you don’t go, we’ll send you back to the center,” an official said.

Qurban went to a garment factory, which he wasn’t allowed to leave. After 53 days stitching clothes, he was released. After another month under house arrest, he finally was allowed to return to Kazakhstan and see his children. He received his salary in cash: 300 Chinese yuan, or just under $42.

Long an ordinary herder who thought little of politics, Qurban used to count many Han Chinese among his friends. Now, he said, he’s begun to hate them.

“I’ve never committed a crime, I’ve never done anything wrong,” he said. “It was beyond comprehension why they put me there.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.