Your trash is suffocating this Indonesian village. Here’s how:

BANGUN, Indonesia — Few Americans have heard of this village, wedged between peanut farms and a paper mill on the island of Java. But the people here have gained an intimate familiarity with the United States — by rooting around in its trash.

They have combed through ripped sleeves of Oreos, empty packages of Trader Joe’s meatballs, discarded “Lord of the Rings” DVDs and dented plastic shampoo bottles. They have even discovered the occasional $20 bill.

“It’s amazing sometimes,” marveled 43-year-old Eko Wahyudi, “what American people throw away.”

He is one of the many scrap dealers in Bangun, a village of 1,500 families at the receiving end of a transoceanic waste trade worth more than $1.5 billion a year.

The U.S. and other wealthy nations have long sent cargo ships of scrap to Asia, where it is sorted and recycled to fuel industries hungry for raw materials. Indonesia imports large amounts of used paper to turn into cardboard.

A dirty secret of the waste trade, however, is that the paper shipments often include other garbage — such as municipal trash — that can’t be used in manufacturing.

But even that has value in Indonesia. Paper mills sell the trash to nearby villages, where cottage industries have popped up to pick through it and extract any remaining value.

In Bangun, where most of the 1,500 families work in waste, recyclers are after aluminum cans, metal wire and hard plastic that can be cleaned and fed back into industrial use.

Whatever can’t be resold — colored soda bottles, grocery bags, food packaging — winds up lining the roadsides and blanketing fields, catching in trees, tumbling into waterways and turning the village into what some describe as a toxic dump.

The arrangement may not last much longer.

Under pressure from environmental groups, Indonesia and other Asian nations have started cracking down on imports of foreign waste in an effort to reduce soil, water and air pollution.

Since June, Indonesian officials have sent more than 330 containers of waste back to where they came from — including at least 148 to the United States — because the shipments violated laws against importing household trash or hazardous materials. Hundreds more containers have been seized and are under investigation.

Environmentalists cheered the news. Residents of Bangun had a different reaction.

“Waste from the U.S. means jobs here,” said Wahyudi, who once employed 20 workers to sort trash outside his green-painted house, paying them about $3.50 per day.

As his revenue plunged by 80% this summer, he let several workers go and shifted others to part-time hours.

“Everyone here depends on this trade — the rich and the poor,” he said. “Without it, our village suffers.”

Plastic farmers

The scrap trade started here in 1980, when an industrial paper plant opened next to the village. Families that had cultivated peanuts and rice paddies for generations found they could make a quick buck by thumbing through the imported waste the factory didn’t use.

Now they call themselves plastic farmers.

“There’s more money in waste, and you don’t have to wait for a harvest,” said Misna, a woman in her mid-40s who has worked as a scrap picker since she was a teenager.

Misna, who like many Indonesians has only one name, was dragging a rake across a vast open field carpeted with spongy, ankle-deep plastic, trying to unearth anything of value.

Strips of polyethylene bags fluttered in the hot afternoon breeze. Candy wrappers occasionally took flight, like grimy butterflies.

She was focused on a fresh truckload of mixed waste that a group of scavengers had bought for about $15. They hoped to earn double that amount by sorting it and reselling to a scrap dealer.

Misna sat down in the shade of a lean-to next to her 7-year-old granddaughter, sprawled on a patch of scrap. Adjusting her conical hat, Misna began examining bits of plastic, holding each up to the sunlight like a gem as she sorted items into buckets.

Aluminum cans, tubs of detergent and other hard plastic would fetch the most. But the vast majority of the truckload was worthless and would just add to the acres of plastic covering the landscape.

Even some of that gets used — as cooking fuel.

A few miles up the road, a truck deposited several large sacks of plastic strips and tattered shopping bags at the entrance to a tin-roofed factory owned by Budi Santoso. Moments later, a shirtless worker combined the plastic with sawdust, lit the mixture on fire and began to fry a large vat of tofu, which Santoso sells to local shops.

The 39-year-old shrugged as dark smoke spewed from the chimney.

“I know burning wood is better,” he said, “but plastic is half the price and easily available.” Neither he nor his dozen workers complained of illness from the fumes.

The scrap trade has helped Bangun’s mostly Muslim families prosper, take pilgrimages to Mecca and pay for their children’s educations. Houses wear fresh coats of paint and every one has at least one car or motorbike parked outside, sometimes next to a hillock of scrap.

Some residents complain of dust from the waste delivery trucks or the smoke that hangs over the village when plastic is burned. But most residents take pride in their association with trash, saying it attracts workers from neighboring villages.

“The first time people come here, they think it’s dirty,” said Suwarno, a 42-year-old deputy village chief. “But after a while they see the reality, that they can make money.”

A mechanic at the paper mill for two decades, Suwarno and his family sift through trash at home in the evenings. He dismissed concerns about health risks, saying his parents had lived into their 60s.

“They died of diabetes,” he said, stifling a chuckle. “That’s a rich person’s disease!”

The parade of waste deliveries to Bangun has slowed from 10 to 15 trucks a day last year to just a few each week. Most of what the village receives now is Indonesian waste, including domestically made plastic, which he said was of lower quality and worth less to recyclers than scrap from Western countries.

One scavenger said that last year she earned $7 or $8 a day, but now was fortunate to earn $1.

A problem with trash

Indonesia, a vast archipelago of 270 million people, already struggles with managing its own trash. Its cities generate 115,000 tons of garbage a day — 85% of which isn’t recycled, according to the World Bank.

That‘s not much compared with what Americans produce, but experts believe that much of Indonesia’s trash ends up in the ocean and other water bodies. Last year, the East Java conservation group Ecoton found traces of microplastics in river fish, apparently from ingesting diapers dumped in the Brantas River.

“Trash from foreign countries just makes this worse,” said the group’s director, Prigi Arisandi.

Indonesia’s waste imports surged in 2018 after China, long the biggest buyer of Western scrap, banned nearly all foreign waste for environmental reasons.

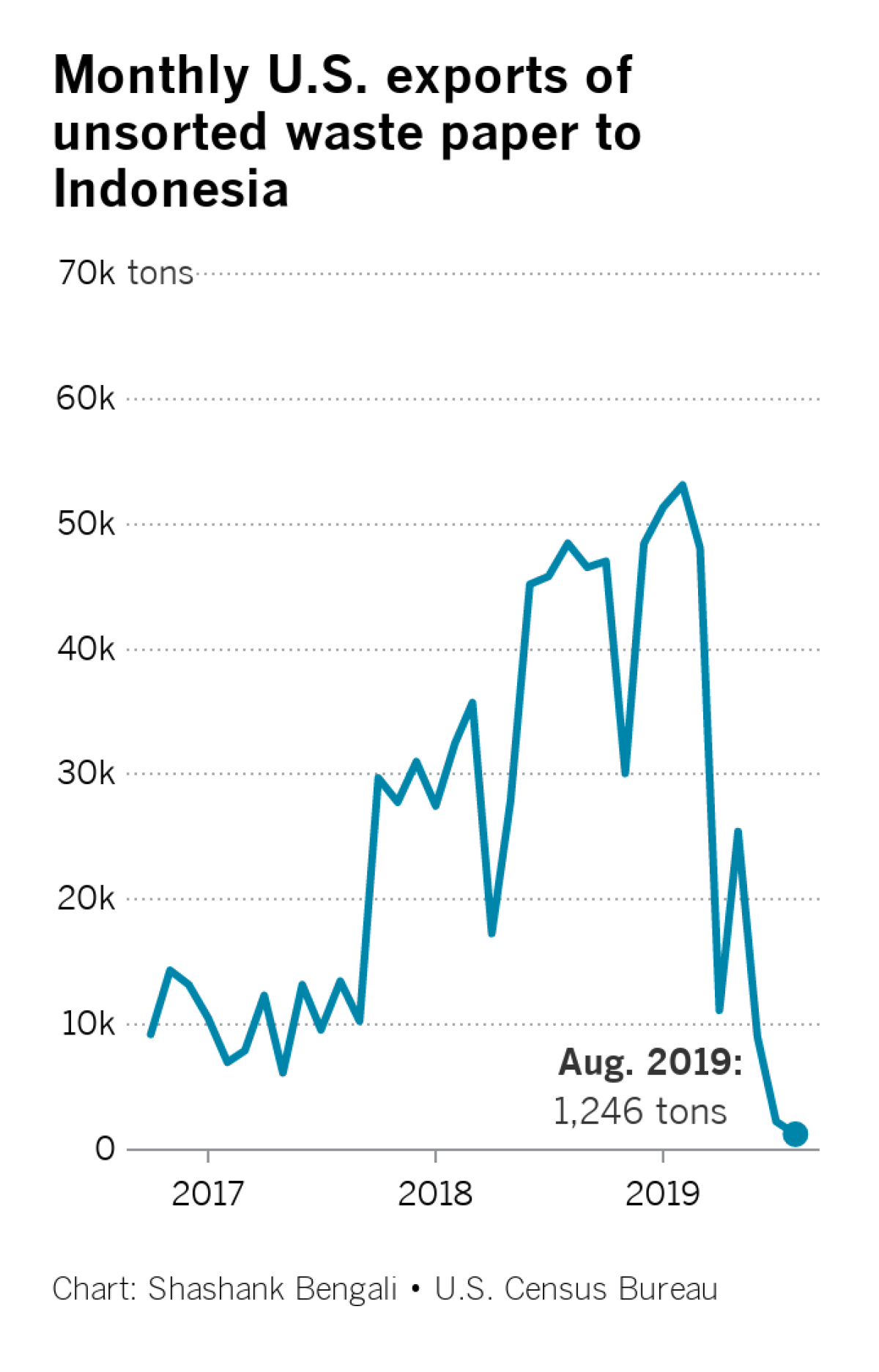

Last year, according to federal trade data, the U.S. exported 452,000 tons of unsorted waste paper to Indonesia, more than in the three previous years combined.

Much of that was purchased by two dozen paper mills in the coastal province of East Java and waved through the busy Tanjong Perak port with minimal customs checks. Environmental groups soon noticed more plastic waste piling up in villages and washing into the Brantas.

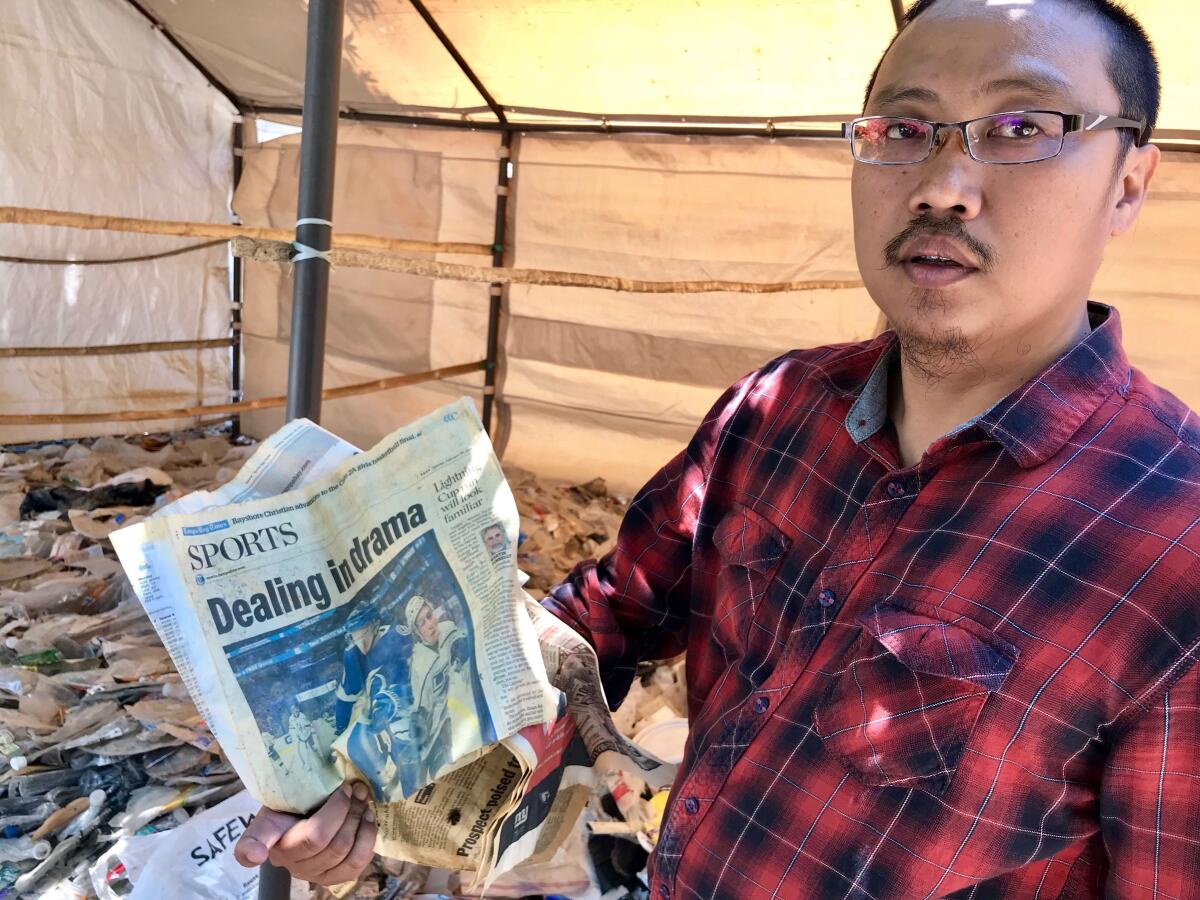

In April, Arisandi conducted a sting operation in which he paid a paper factory $250 for about 1.6 tons of garbage, which trucks deposited in a field behind his office.

Staff members quickly determined that some of the trash had been imported recently from the U.S.: Tucked inside one bale was a yellowed copy of the Feb. 26 sports page from the Tampa Bay Times. The group also found packaging that appeared to originate from Canada and Britain.

After Ecoton reported its findings, customs officials seized 127 containers that the paper mill had purchased from American companies. The exporters agreed to reclaim the containers, which were shipped back to the U.S. in July and August.

As of mid-October, no importers had been penalized for violating Indonesian laws against importing contaminated waste. Indonesian officials said they did not know whether foreign exporters had faced punishment.

American officials said they were disappointed to learn of the contaminated shipments but could do little to stop the transactions, and called on Indonesia to strengthen enforcement of its import rules.

As countries such as the Philippines, Malaysia and Vietnam enact their own restrictions on imported waste, especially mixed plastic, the U.S. is keeping much more of its garbage at home, where it is deposited into landfills or incinerated.

U.S. waste paper exports to Indonesia plummeted from 53,000 tons in February to 1,200 tons in August, the lowest in 15 years.

“Countries should sort their own waste and not send their toxic products to Indonesia,” said Alvina Christine Zebua, a customs official at the port in Tanjong Perak. “The Indonesian government is working together to create rules to ensure that waste like this isn’t allowed in the country anymore.”

She expressed little sympathy for Bangun, but the villagers aren’t giving up and have appealed to authorities for licenses so they can continue to work in waste. Few can go back to farming, having sold land to invest in the scrap trade or watched their soil overtaken by plastic.

“For people here, there is nothing more valuable,” Suwarno said. “There is still hope that foreign waste will come back.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.