‘This is our land’: How a tiny Alaskan village stymied Pebble Mine

PEDRO BAY, Alaska — Mine company managers came bearing gifts 15 years ago for residents of this Native village at the far end of Alaska’s biggest lake, off the state’s road system.

Alighting from a plane on Pedro Bay’s gravel airstrip, the representatives of Canada’s Northern Dynasty Minerals brought platters of catered food to the community of 40 people, who traditionally subsist on salmon and moose. In a meeting, the mining men described a project the villagers could hardly imagine.

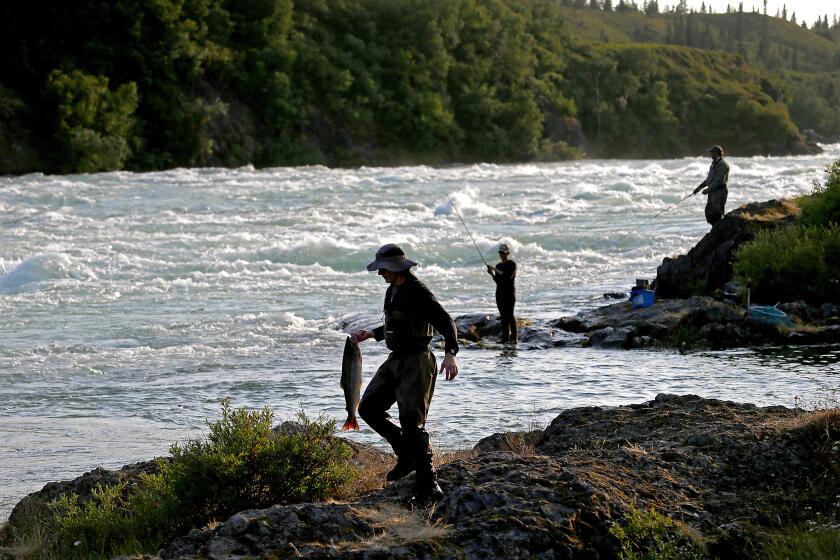

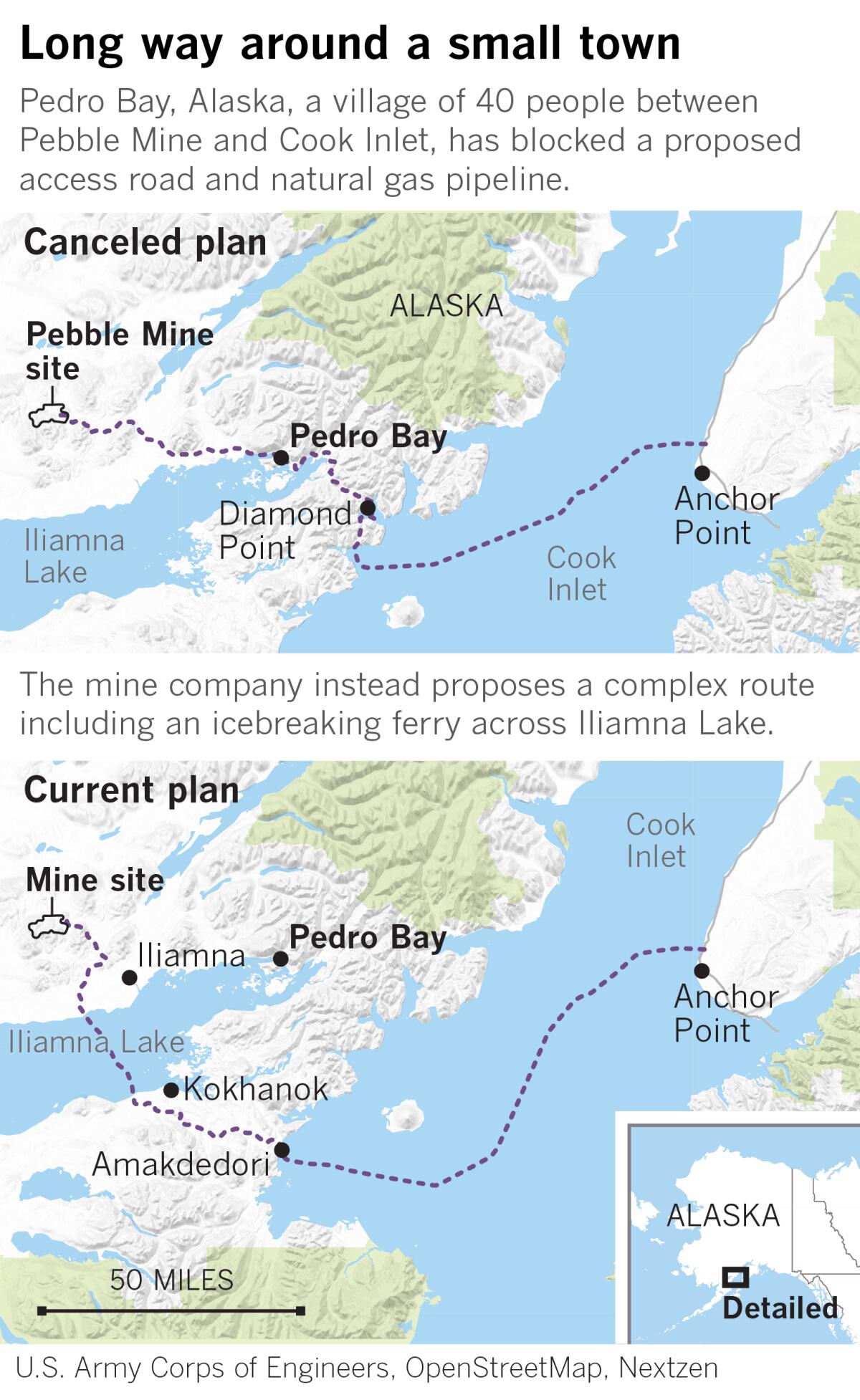

They wanted to put a giant open-pit copper and gold mine north of Iliamna Lake in the headwaters of Bristol Bay, home of the world’s biggest wild sockeye salmon run. For transport and power at the remote site 200 miles southwest of Anchorage, Pebble Mine would require more than 100 miles of roads coupled with a natural-gas pipeline crossing Cook Inlet.

The most direct route to bring supplies and fuel in, and ore out, appeared to pass right through Pedro Bay land in a development only possible if the village’s Native corporation granted access.

The company representatives spoke of jobs and potential windfalls for the village, such as scholarships and a recreation center. Later they took residents of Pedro Bay and other lakefront communities on well financed trips to distant cities, so they could see for themselves the jobs and other benefits that mines could bring.

A giant open-pit copper and gold dig above Alaska’s Bristol Bay could yield sales of more than $20 billion in two decades, but Pebble Mine would place the world’s greatest wild salmon run at risk forever.

Some residents were tempted. But over the years, Pedro Bay villagers grew suspicious of the project, which would rely on giant earthen dams to keep hazardous mine tailings from seeping or surging into rivers flowing into the lake. Pebble Mine, which the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is considering whether to permit next year, would wipe out more than 3,400 acres of wetlands and 81 miles of streams.

Ultimately, tiny Pedro Bay said no.

In a July 1 letter to the Army Corps, the chief executive of the community’s Native corporation called the mine an “existential threat” to subsistence fishing and cultural traditions. Matt McDaniel wrote that tribal land could not be used for anything to do with the project.

The rejection put Northern Dynasty in a bind. Pedro Bay occupies a narrow passage between impassable mountains and the lake, a crucial eye in the needle that planners had envisioned threading, connecting the road and pipeline to a potential Cook Inlet port at Diamond Point.

But the company’s U.S. subsidiary, Pebble Limited Partnership, was ready with an elaborate work-around: an ice-breaking ferry to carry ore 18 miles across the lake — and from there, a 37-mile road to another Cook Inlet seaport called Amakdedori. The natural-gas pipeline would parallel the route, under the company’s currently preferred scenario, crossing the lake and continuing alongside another length of road 29 miles to the mine.

Yet the channel that the icebreaker would keep open 365 days a year would cut the frozen surface used in winter as a highway to connect villages around the lake. A rare species of freshwater harbor seal might also be affected.

Keith Jensen, Pedro Bay Village Council president, acknowledged that ruling out the mine’s most direct access route may well create an economic and environmental ripple effect. Jensen knows that adding a ship route would change the character of other remote Native villages, especially Kokhanok, a community of 170 near the ferry’s proposed southern terminal.

“Somebody might say it’s selfish, but I don’t want to see it in Kokhanok’s backyard, and I certainly don’t want it in my backyard,” Jensen said.

As Northern Dynasty pursues the Army Corps permit and seeks new investors, Pedro Bay is quietly undergoing its own resurgence.

The population had dwindled in recent years, and the village’s Dena’ina School closed in 2010 after graduating just two high school students. Summer residents accounted for much of the businesses at the village’s tiny post office run by Jensen’s sister in the tradition of their late father, Carl, who was one of the last U.S. postal workers to carry mail by dogsled.

But a pastor with a young family has arrived to reopen the church. Some young adults who left for cities are returning, drawn by the beauty of Pedro Bay’s forest-fringed coves. Wynn Knighton, 31, spent summers in the village as a boy and moved back year-round three years ago.

“It was time, I was done with cities,” Knighton said. He cuts and sells firewood, does odd jobs for the village council, picks berries and cures salmon in a homemade smoker.

Sam Herrick, 26, also moved back with her new husband, whom she met in Alabama during a three-year stint as a bookkeeper. Herrick and Knighton are staunch opponents of the mine.

“This is our land,” Knighton said. “Why would we give up our salmon grounds, our berries and our ice on the lake for somebody else’s money in their pocket?”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.