Behind the story: Trying to explain how one man’s faith sustained him during tragedy

VERNAL, Utah — On the occasion that I teach a journalism class, I am sometimes asked where I find my stories. I’m sure my answer isn’t what the students hope for.

Good stories arrive unannounced: buried in the back pages of a local newspaper, caught in a quick aside with a friend, a sentence in an email. Discovery is a humbling experience.

But, I tell students, finding a good story is less important than answering the essential question behind a story.

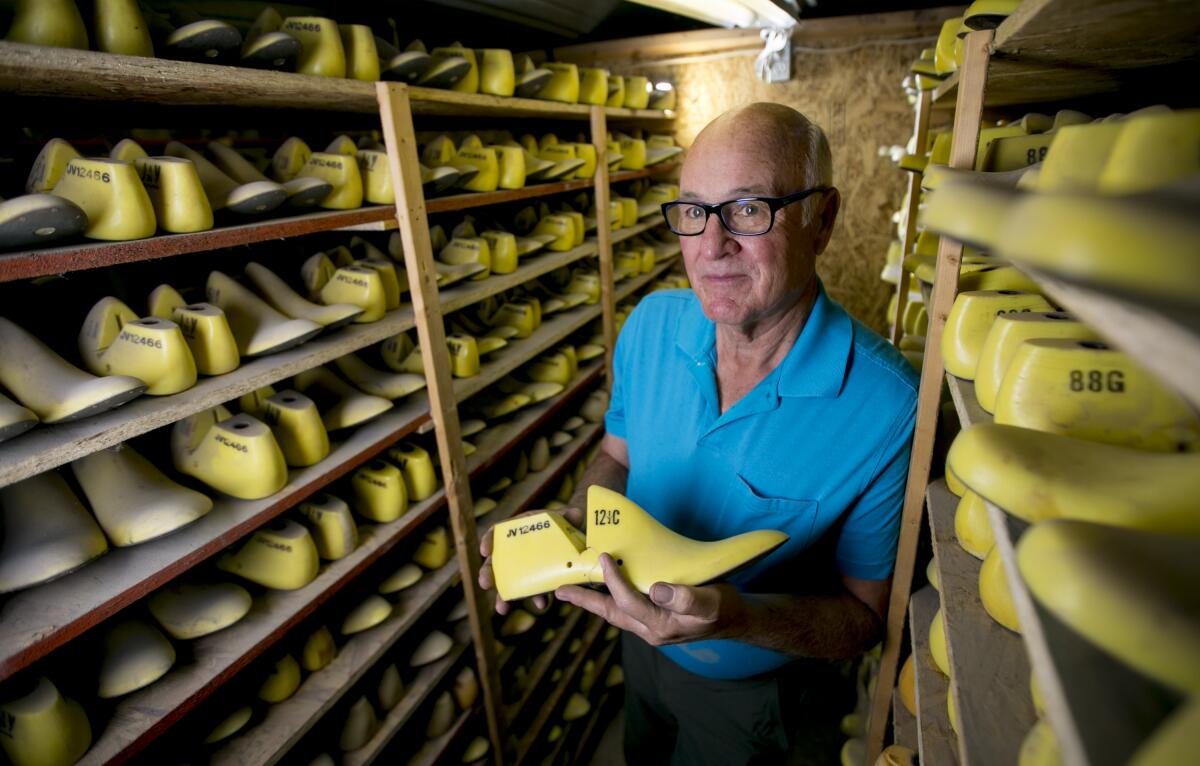

When I got on a plane for Vernal, Utah — to be fitted for a pair of custom hiking boots by one of the country’s most gifted boot makers — I thought I knew the question. What meaning did Randy Merrell find in a business marginalized by mass production and digital design?

I had asked this question of a clock maker, a farrier and a calligrapher, and I knew that these trades opened a door on traditions whose lingering grasp on the culture made them all the more compelling. A cobbler should be no different.

But I had a second question as well. Only I didn’t know if I’d be able to ask it. I worried it might be too intrusive.

I had read about the deaths of Merrell’s wife, LouAnn, and his step-grandson, Jackson, swept away while crossing a creek in the Grand Canyon two years ago. Merrell and his daughter-in-law were present and had survived.

I wanted to know if he had come to accept the terrible loss of that day and how would he explain that acceptance. What words do you put on a tragedy that seems only to prove that life is fickle, random and cruel?

I have been asking this question for most of my career.

Answers lie somewhere in the story of a young man who was the sole survivor of a helicopter crash in Afghanistan, or of a man shot on his way home from a party, or of a father and daughter attacked by a grizzly in Glacier National Park.

On the night I arrived in Vernal, I had dinner with Merrell, and he set me at ease. A reluctance to speak about tragedy is more awkward than directly addressing it, and he was willing to address it.

A 6-foot-5 man with size 17 feet traveled to the middle of nowhere in search of a boot maker. What he encountered was a life deeply touched by love and death and leather.

He shared that in 2004 he had lost his son and, in 1982, his father. Like LouAnn and Jackson, they too had perished in accidents without any warning. One day the sun rose, then set, and the darkness was all the greater.

What’s more, Merrell contracted West Nile Virus in 2008, a disease that progressed into meningitis. He was incapacitated for nearly five years and nearly shut down his business.

He is clearly a man well-versed in the fragility of life, and throughout it all, his faith — supported by his church, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints — helped him through moments that seemed most desolate. But faith in the face of such loss was not always easy.

On the day that his father died — in a construction accident in front of him — Merrell got home from the hospital. It was night, his clothes still covered with blood, and he went out into the fields to be alone. Under the dark and starry sky, he screamed and shouted at God.

But then, he said, he felt something change inside of him, an easing of his pain that he attributes to God putting his arm around his shoulder and consoling him.

The week that I spent with Merrell, he recounted similar encounters: the rustling of the covers of the bed, fireflies unexpectedly swarming in a field, friends sharing visions of LouAnn, coincidences that just might not be coincidental.

I listened carefully, trying to accept these stories and, at the very least, understand the effort of a grieving man to give meaning to his loss and allay his sorrow. Who was I to question what he believed?

His words opened up worlds of such signs and wonders that I felt in his company a porousness between this world and some other. I thought about the visions of William Blake, of Renaissance painters, of a time not so long ago when angels and ghosts walked the earth and people claimed to see them. Clearly this propinquity was Merrell’s solace.

I am no visionary, nor am I religious. I wanted Merrell’s certainty and conviction to make sense to readers, who I worried would dismiss them as figments of an imagination supported by his church. Just as his faith provides him with meaning for his losses, I wanted his story to provide meaning as well.

Once home, I wondered if I had answered my question. I turned to the Book of Job. What better story, I thought, to explain the vicissitudes of life. But more than the story of a man as a pawn, a plaything for God and the devil, Job is the story of how we understand the role of suffering in the lives of others.

Having lost his family, fortune and health, Job is approached by three companions who at first sit quietly with him by way of comforting him. But their patience seemingly runs out, and they try to find reason for his plight. Their words, insensitive and judgmental, come across as attempts to safeguard themselves from such calamity.

In the end, though, God answers with a thunderous, if not peevish, rebuke. Chronicling the details of his creation, he resorts to his authority: Any attempt to understand misfortune is meaningless because mortals haven’t the wisdom to see beyond their own fear and grief.

The message is clear: We may question, we may scream and shout, we may curse the burdens we’re asked to carry. But in the end, nothing can explain the precariousness of life, nor ease the pain.

The greatest tragedies are the most arbitrary tragedies, and the most meaningful narrative does not try to explain them.

And sometimes that just might be enough.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.