Stymied by U.S. asylum policies, many migrants on the border are heading home

NUEVO LAREDO, Mexico — When U.S. officials walked about 200 asylum seekers south across the bridge from Texas last week, the migrants were clutching court paperwork, planning to stay in Mexico as they pursue their cases.

But their hopes fizzled as soon as they viewed their temporary home: a trash-strewn parking lot at the edge of the bridge. The treeless concrete expanse, wedged between the river and a Mexican immigration building, was already packed with 250 returnees, some of whom had been there for 10 days.

This was not what U.S. Customs and Border Protection officials had promised migrants under the Trump administration’s “Remain in Mexico” program. Designed to prevent asylum seekers from skipping court and disappearing into the U.S. illegally, the program requires them to await the outcome of their cases in Mexico while allowing them to cross legally for court hearing. Most must wait several months just for their initial hearing, and few have access to immigration lawyers in the U.S.

At the Nuevo Laredo parking lot, as Mexican officials came and went from an air-conditioned office, migrants camped on pallets strewn among their cars. Some huddled under a metal carport, sharing a foul-smelling bathroom and bathing with outdoor hoses. Children played with empty water bottles and shards of glass.

Honduran migrant Jose Antonio Mancia Hernandez couldn’t imagine staying with his 10-month-old son, Dylan, until their next court hearing Sept. 20.

“It’s like a psychological thing they’re doing, trying to make us go back to our countries,” he said.

“They don’t secure us, we can’t bathe, they don’t have food — they treat us like dogs,” said Claudia Lopez Galvez, 37, who had fled Guatemala with her 16-year-old daughter.

Over the last five months, the U.S. has returned more than 20,000 asylum seekers to Tijuana, Mexicali, Juarez, Nuevo Laredo and Matamoros, according to Mexican officials. An analysis of immigration court records by the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse at Syracuse University showed that 1,155 “remain in Mexico” asylum cases had been decided by the end of June — only 14, or 1.2% — with attorneys. Not a single person had been granted asylum, and 12,997 cases remained pending.

It’s not clear how many asylum seekers sent to wait in Mexico have abandoned their legal cases and headed back to the countries they fled. A Mexican official in Baja California state estimated about half there had left for home.

Along the border in recent days, thousands of migrants have faced the same quandary. Many now penniless or saddled with debt from their trips north have decided to head back. Some said they still planned to pursue their U.S. immigration cases, but many more said they just hoped to make it home without being kidnapped or killed.

Nowhere is safety more of a concern than in Nuevo Laredo’s Tamaulipas state, where 3,000 migrants have been returned despite U.S. State Department warnings against traveling there due to kidnappings and other violent crimes, according to José Martín Carmona, head of the state government’s Institute for Migrants.

The entrance to the parking lot where the migrants waited near the border bridge lacks armed security. The migrants were desperate for food. Some children begged their parents for a drink of water.

Last week, Nuevo Laredo’s six official migrant shelters were full — and not accepting those returned from the U.S., said the Rev. Aaron Mendez Ruiz, who runs Casa Amar. The 100-bed shelter is housing 160, although in recent months it accepted even more migrants, allowing them to sleep in the courtyard and nearby street.

“In all the border cities, this is a problem,” Mendez Ruiz said, and busing migrants south “is the only solution.”

Vendors, meanwhile, have swooped in to gouge the returnees stranded in the parking lot for cell phone charging, diapers and clothes, among other things. Couriers, who charged a fee to pick up money relatives had wired to those waiting in Nuevo Laredo, sometimes vanished with the cash. Some families said they had spent $500 in four days on food and water alone.

No doctors or lawyers visited Thursday, although immigration officials summoned an ambulance twice for children who were suffering from the 104-degree heat.

Honduran Katherine Zavala’s 3-year-old daughter, Brianna Ramos, had a fever, but Zavala was afraid to take her to the hospital.

“I asked if they could take her to the hospital,” Zavala, 23, said of Mexican immigration officials at a nearby building. “They said I could take my chances with my life.”

Some migrants separated from children, spouses and elderly parents in detention scrambled to figure out whether they too had been returned to Mexico, and if so, where. A Colombian woman with a toddler discovered her 20-year-old son had also been returned to Matamoros, over 200 miles away by car.

Honduran Ines Posas, 27, said that being sent here with her 7-year-old autistic son felt “like a punishment.” She said that’s what a Border Patrol agent told her it was. The single mother had hoped to join her father in Louisiana or her mother in South Carolina, but said now: “I just want to go back to my country.”

Security guards at the parking lot warned that stepping outside put migrants at risk of being kidnapped by local drug cartels.

Those who had traveled north with smugglers had “keys,” or codes, to provide cartel members who stopped them on the street, but many had crossed east of Nuevo Laredo, the territory of different smugglers. Some migrants said they had seen people snatched from the parking lot in recent days, including two Cubans who were held for $8,000 ransom.

Some migrants who were returned to Mexico have attempted to re-enter the U.S. again illegally — and have died in the process.

On Thursday, Mexican officials in Nuevo Laredo recovered the body of an unidentified man from the Rio Grande near the bridge where migrants awaited buses south. On Monday, officials in El Paso found the body of Vilma Mendoza, 20, a Guatemalan migrant who entered the U.S. on the Fourth of July. She was returned to Juarez and drowned trying to cross again.

Those who chose to wait in the parking lot included pregnant women and people still wearing hospital bracelets from being treated while in Border Patrol custody. Their only alternative: Mexican government-contracted buses to Tapachula, Chiapas, on the border with Guatemala. Some of the migrants had to ask where whether Chiapas was in Mexico.

“They told us cross [the bridge into Mexico] and there will be a shelter; the conditions are better there. But it’s not true. There’s none of that. It’s a lie,” said Miriam Orillana, 33, who fled El Salvador with her disabled 5-year-old son, Carlos, hoping to join her husband in New York.

After living in the parking lot for a week as her son grew increasingly manic, she decided to take the first bus to Tapachula on Thursday, but still planned to return to the border for an Oct. 29 court date.

Others wanted to head to the northern Mexican industrial city of Monterrey, where they figured they could find work and support themselves while awaiting their asylum hearings. But Nuevo Laredo officials last week stopped sending free buses there. Migrants said they were told they would have to pay not only for tickets, but $1,200 each for protection from the cartels to leave the parking lot and reach the local bus station.

Breast cancer survivor Patricia Paiz, 43, decided to send her 14-year-old son back to Guatemala with a friend’s family while she tries to reach Monterrey, find work and pursue her asylum case.

“With Donald Trump, things will not change. Maybe after the elections,” she said. “But for now, no.”

Many more migrants stranded in Nuevo Laredo had decided to give up on asylum and leave.

“I don’t want anything else to happen to me,” said Lili Verona, 48, a Honduran migrant who came north hoping to join relatives in Los Angeles or Miami.

Single mom Elisa Reyes fled Honduras with her 14-year-old daughter and 8-year-old son to join family in Los Angeles, but after spending 10 days watching her children vomit and shiver in Border Patrol detention and a day in Nuevo Laredo without food, she was leaving on a bus for Chiapas, heading toward home.

She called the U.S. immigration system “a deception.”

In Tijuana last week, Danny Mejia, 35, said he had also decided to abandon his asylum case before his first hearing Oct. 28.

“My dream is gone,” the Honduran migrant said as his wife and 8-year-old son received water and snacks from volunteers at a tent by the border crossing. “We don’t know anyone. We don’t have any money. We don’t have a place to sleep. The only thing we can do is go back to our country.”

Tijuana shelter directors said about 40% of migrants had decided to return home in recent weeks.

“I feel like a recycling center,” said the Rev. Albert Rivera, who runs the local Agape shelter and has been helping migrants arrange bus trips and flights home. “The minute I drop off a group at the bus station, immigration calls me again with new people to pick up.”

At his shelter Thursday, migrants were signing up for free flights home from the United Nations’ International Organization for Migration. The group has also offered free bus rides to returnees in Juarez.

Juan Santos said that without a job, he couldn’t await his first hearing Jan. 17. He and about 30 other migrants accepted U.N. flights to Honduras next week.

The cities where asylum seekers are being returned by U.S. officials are among the most dangerous in Mexico. Amnesty International has called for an investigation into the fatal shooting of a Central American migrant father Wednesday by Mexican authorities in the northern city of Saltillo.

In Nuevo Laredo, Honduran farmworker Edin Santos Martinez, 38, and his 15-year-old son said they came north to join his brother in Los Angeles, but had been kidnapped twice along the way. In the southern state of Veracruz, they were held for three days until they paid $6,000. Then they were held again for a week on the border in Tamaulipas until they paid $8,500. That’s in addition to the $10,000 Santos Martinez paid smugglers.

“If anything happens to us over here, it’s the responsibility of the government over there,” he said, pointing to the U.S. “What else can we do?”

In the early hours Friday, as some migrants waited for buses to Chiapas, they shifted toward the Rio Grande and away from the parking lot entrance as rumors spread that members of the Zetas cartel were circling outside, looking for targets.

“If you value your life,” a guard told a Colombian migrant mother, “take the buses.”

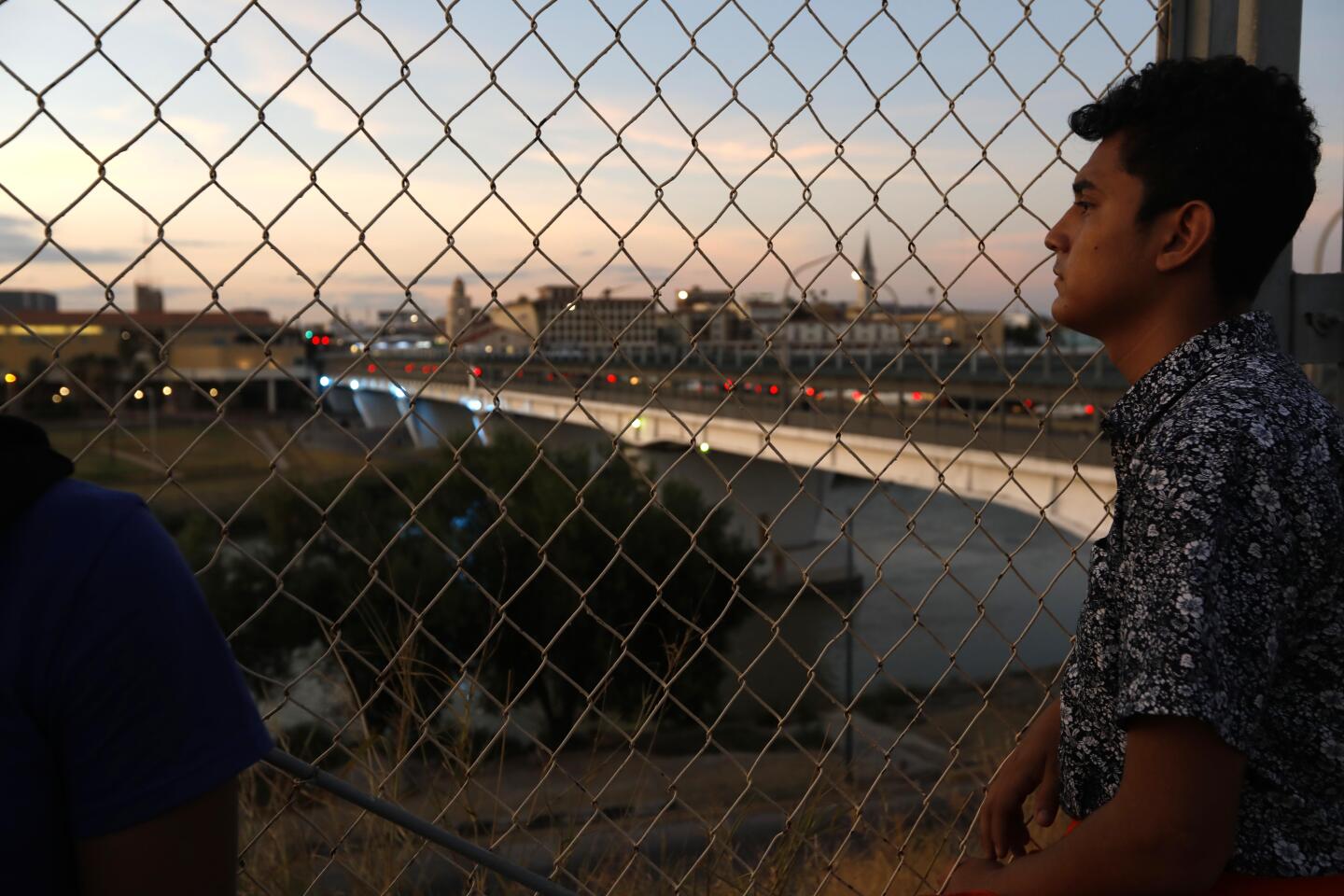

Officials wouldn’t say when the buses would arrive. Migrants bedded down near where they hung clothes to dry on a chain link fence with a view across the river, where the U.S. government is building tents to process and hear more “Remain in Mexico” cases.

When the buses finally arrived in Nuevo Laredo around 1 a.m., nearly 200 migrants rushed to line up. Many were smiling, relieved. One woman exclaimed: “Thank God we can go!”

Eber Ramirez, 42, joined the line with his 15-year-old daughter and 18-year-old niece. They had hoped to make it to relatives in Maryland and Virginia. But after nearly a week in detention, Ramirez said he was tired of discrimination and convinced he couldn’t support himself in Mexico long enough to win asylum in the U.S.

He would return to Guatemala, he said, with a message for his family about the U.S.: “Never go back.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.