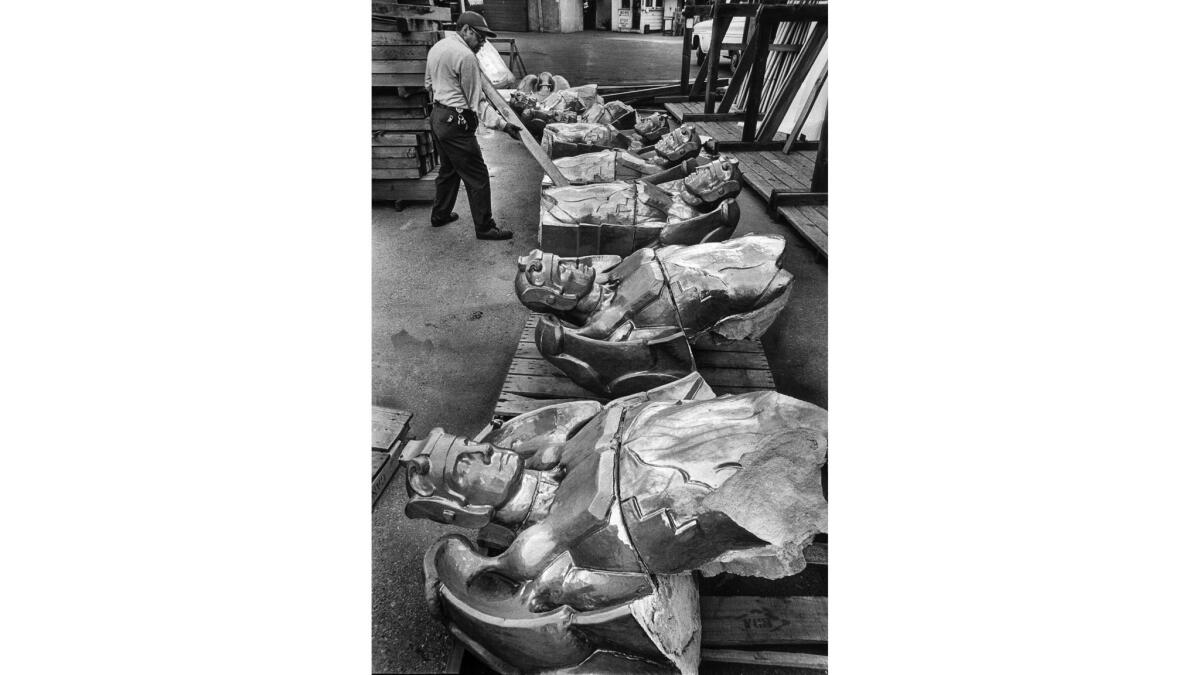

From the Archives: Richfield Building sculptures in wrecking yard

In 1969, the Richfield Building – also known as the Richfield Tower – was demolished. The building’s terra cotta angels were saved and put up for sale.

This photo by staff photographer John Malmin appeared in the April 10, 1969, Los Angeles Times. In an accompanying story, staff writer Dave Felton reported:

For 40 years they stood guard over the black-gold fortress at Flower and 6th Sts. that was the Richfield Building.

From 15 floors they watched Los Angeles around them grow from simple order to smoggy complexity. They saw the gaudiness of their own building turn to art.

Now they lie strewn about a Cleveland Wrecking Co. yard like a defeated army.

Soldiers? Is that what these mysterious creatures were supposed to be? Soldiers with golden wings?

Maybe angels. But angels with Roman helmets and breastplates?

“I don’t know what the heck they’re called,” an employee at Cleveland Wrecking said Wednesday while poring over invoices.

“I know we’re selling ’em for a hundred bucks each. It cost us that to tear ’em down.”

He said they were hauled into the yard at 3170 E. Washington Blvd. about a month ago. There are 40 of them.

Workmen arranged them in several rows, some sitting straight up like a Harvard crew, some lying on their backs. A few have fallen forward, their gold-colored Roman noses buried in asphalt.

Other than being ripped from the building at waist level, the figures suffered few casualties – a broken nose here, a clipped wing there. Two were decapitated.

After 40 years in sun and rain their brilliant gold glaze remains only in recesses, their eye sockets, their navels, the insides of their wings.

During all that time they faced only one real test as guardians of the Richfield Building. And they blew it.

The Cleveland Wreckers picked them off easily, one by one. “It took about two weeks,” said Dick Laws, superintendent of the job. “We put a choke around the neck and one around the waist and just cut away the concrete.

“I’ll say this, they came down a lot harder than they went up.”

Laws didn’t know what the figures were supposed to be called. “They usually call those things gargoyles, don’t they? At least they served that purpose,” he said.

Neither did Mickey Parr, a public relations man at Atlantic Richfield.

“I guess nobody around here has ever bothered to ask,” he explained. However, he dug out a 1930 copy of Arts and Architecture and read the following caption:

“Heroic in size, impressive in conception, are the sculptural figures designed by Haig Patigian which crown the main walls with a fairly regal procession of silhouetted torsos.

“This figure is a highly conventionalized suggestion of motive power.”

“I don’t know what it means either,” said Parr.

“Perhaps the oil executives of the day considered them merely expansive hood ornaments.”

A few of the guards have survived. In 2010, staff writer Bob Pool reported on one of the guards: Watching Over an old L.A Sentry.

I’ve posted two photos from that story below.

This post was originally published on May 24, 2016.

See more from the Los Angeles Times archives here

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.