8 joyful places in L.A. that tell the story of the Filipino American experience

When we were kids, my sister Clarizza and I would take the bus from our home in Eagle Rock to Melrose in the Fairfax district, a trip that would take four hours with transfers and the inevitable delays. We didn’t mind, though. Holding hands, we’d stare out the window, watching Los Angeles transform from neat terracotta houses to busy sidewalks dotted with fruit vendors slicing up watermelons, mangos and coconuts.

I like to think that in those moments, we were two Filipino girls searching for the heart of the city. Our family had immigrated from the Philippines, and we yearned for a place where we belonged, where we could sit and experience the American dream.

It’s an idea that millions of Filipinos in the U.S. carry, and yet for so many of us, that dream can feel difficult to hold. Filipino Americans are the second-largest Asian American ethnic group in the nation, but our community has a complicated history of marginalization. Systemic erasure has made it difficult for us to find and identify our stories.

Planning your weekend?

Stay up to date on the best things to do, see and eat in L.A.

It wasn’t until my late 20s that I learned about Filipino American legacies — how our ancestors landed in what is now Morro Bay on Oct. 18, 1587, how Filipino Americans fought in World War II but those who made it back home were denied recognition and benefits, and how Larry Itliong marched next to Cesar Chavez and led thousands of farmworkers in the Delano Grape Strike of 1965.

I also learned that much of our history can be felt today in physical spaces around the city. Throughout L.A., there are landmarks that celebrate the perennial joy of being Filipino in America, from the Historic Filipinotown arch on Beverly Boulevard to the Polynesian-themed Tiki Ti in Hollywood. These landmarks are proof that Filipinos were here — and will continue to be here.

Check out these places during October’s Filipino History Month, or any time throughout the year, as who we are will never fit into the confines of bookmarked dates. As Filipino artists, political leaders and dreamers continue to do the work, I hope this list grows. And I hope visitors will continue to see that we’re not just a part of America’s history, but an unshakable part of its future, too.

Historic Filipinotown Arch

Designed by Filipino American artist Eliseo Art Silva, the arch, which opened in May, is officially named, “Talang Gabay: Our Guiding Star.” For Silva, who has been creating Filipino mural art across Los Angeles since the 1990s, art is essential to Filipino American identity.

“What do you see when you think of Chinese, Japanese and Korean art?” he asked as I scanned the arch and a neighboring mural.

After pausing a moment, he then asked, “What do you see when you think of Filipino art?”

While most people have a response to the first question, it’s the second that makes many stumble. “We’re not humanized because our stories have not been elevated to art,” Silva said. “And why is that? Because you have been Americanized. There’s no image that connects us to our stories.”

He hopes that the arch is a reminder to visitors that they are entering a place where the Filipino experience is celebrated and remembered.

Filipino Christian Church

Originally located in Little Manila on Bunker Hill in downtown L.A., the church was displaced by redevelopment projects such as the 101 and 110 Freeways. In 1950, it moved to its current home in the Temple-Beverly corridor.

Since being founded by the Filipino Christian Fellowship in 1928, the organization has served as a gathering place for some of the earliest Filipino immigrants. In the 1930s, the space offered a place of community and safety to the Filipino community at a time when signs that read “No Filipinos or Dogs Allowed” and “Positively No Filipinos Allowed” were posted around the city. Today, the church continues to welcome newly arrived Filipinos and acts as a meeting place for organizations uplifting the Filipino American community.

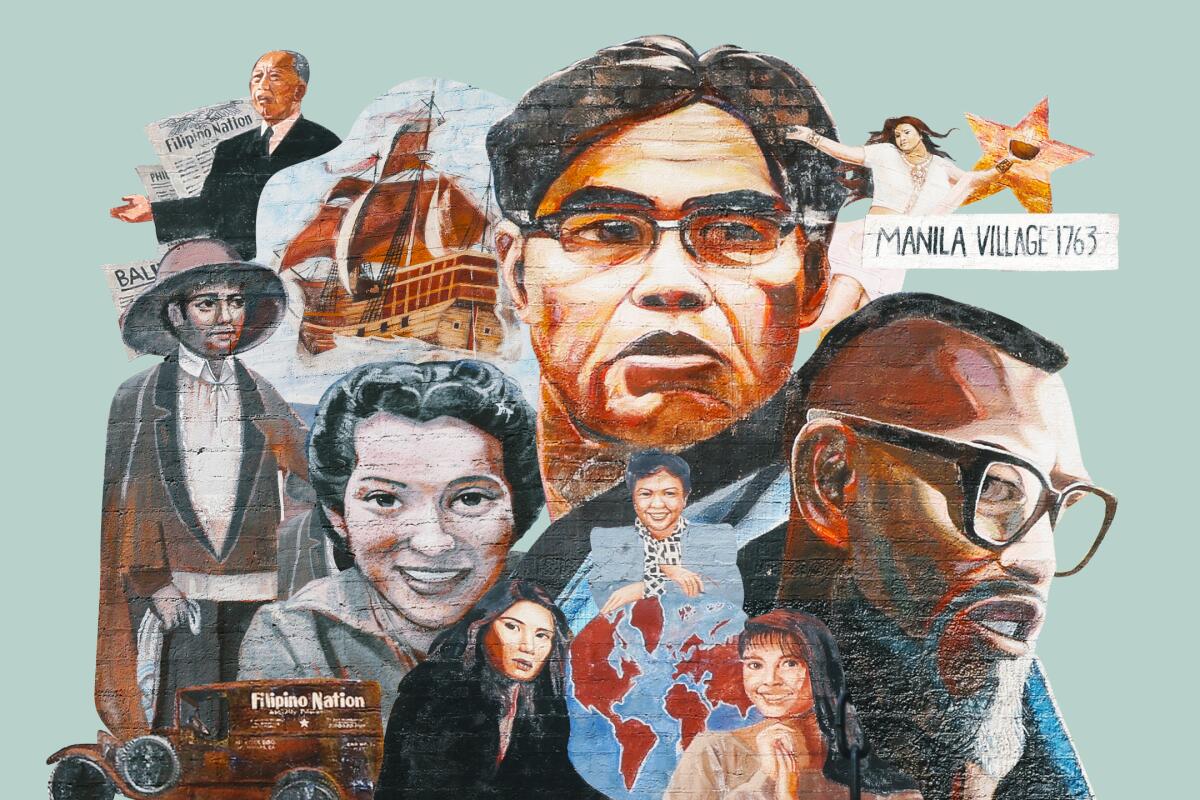

Unidad Park Mural, “Gintong Kasaysayan, Gintong Pamana”

Itliong, whose groundbreaking activism was overshadowed by Chavez for decades, touches the golden Philippine sun, highlighting the Filipino leader’s legacy in American history. Above Itliong’s head, a babaylan, a spiritual and cultural leader, is painted as a diwata, a spirit in Filipino myths. The diwata is holding a lamp. Silva calls attention to this and said that the diwata is “giving honor to Larry Itliong, who made it all happen.”

Filipino World War II Monument

Within a gated park on North Lake Street, five large, black granite slabs stand tall. The lettered slabs spell out “Valor” and each bears a chapter of Filipino American history, starting with the U.S. colonization of the Philippines and ending with Filipino American veterans’ fight for recognition and honor.

Designed by artist Cheri Gaulke, the monument also displays a quote from Faustino “Peping” Baclig, who survived the Bataan death march and led the movement to gain veteran financial and medical benefits. On the center slab, next to a map of the Philippines, the words read: “Bataan was not our last battlefield. We are still fighting for equity.”

When Filipinos returned home after World War II, Congress reneged on President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s promise of U.S. citizenship and thousands of Filipinos were denied full veteran benefits, despite having fought in the U.S. armed services.

Apifannia Beltran, a World War II veteran who visited the monument when it was erected in 2006, told the Times, “I am so touched. It has taken a long time.”

Moncado Mansion

Fun fact: Recognize the exterior? You might know the property as the fictional Fisher & Sons funeral home from the HBO series “Six Feet Under.”

The LA Artbox

One of the first exhibits, “Belonging: A Filipino American Arts and Culture Experience,” brought together Filipino Americans from first, second and third generations. The event featured multidisciplinary artist Francis Gum, who juxtaposed his nostalgia for the motherland and the U.S., and Ryan Jordan, whose work focused on his personal journey as a queer and Filipino artist. “The younger generation right now, or at least the second-generation Filipino Americans, are living their truth and more power to them,” Bernardo said. “Hopefully I can hold space to showcase those kinds of stories.”

Tiki Ti

After three decades working behind the bar at popular joints like Don the Beachcomber, Buhen decided to run his own show, just as Polynesian culture was sweeping up Southern California. In 1961, he opened Tiki Ti and became known as “the finest mixologist in L.A.”

Inside the local haunt, every inch is covered with memorabilia collected for the past 60 years. Blowfish lanterns hang from the ceiling, Christmas lights and license plates line the walls and ceramic tiki mugs fill every shelf.

“This bar was his life,” Mike Buhen, his son, told the Los Angeles Times after his father’s death. “I helped him put the tapa cloth on the wall when I was in high school. He cut the bamboo for the ceiling himself.” The Buhen family continues to run Tiki Ti, and if you stop by, you’ll find Mike serving up the same potent drinks his dad dreamed up during his early days bartending.

Dollar Hits

What began as a food stand in a strip mall in Filipinotown grew into a brick-and-mortar restaurant where customers spill out into the parking lot.

“I am overwhelmed and I am blessed and grateful,” Elvira Chan, the founder and owner of Dollar Hits, told the Los Angeles Times. The establishment has become a staple in a working-class neighborhood that’s being pushed out by gentrification, something that many businesses and residents in the area are fighting.

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.