Norway’s frozen Svalbard is home to a top-of-the-world seed bank

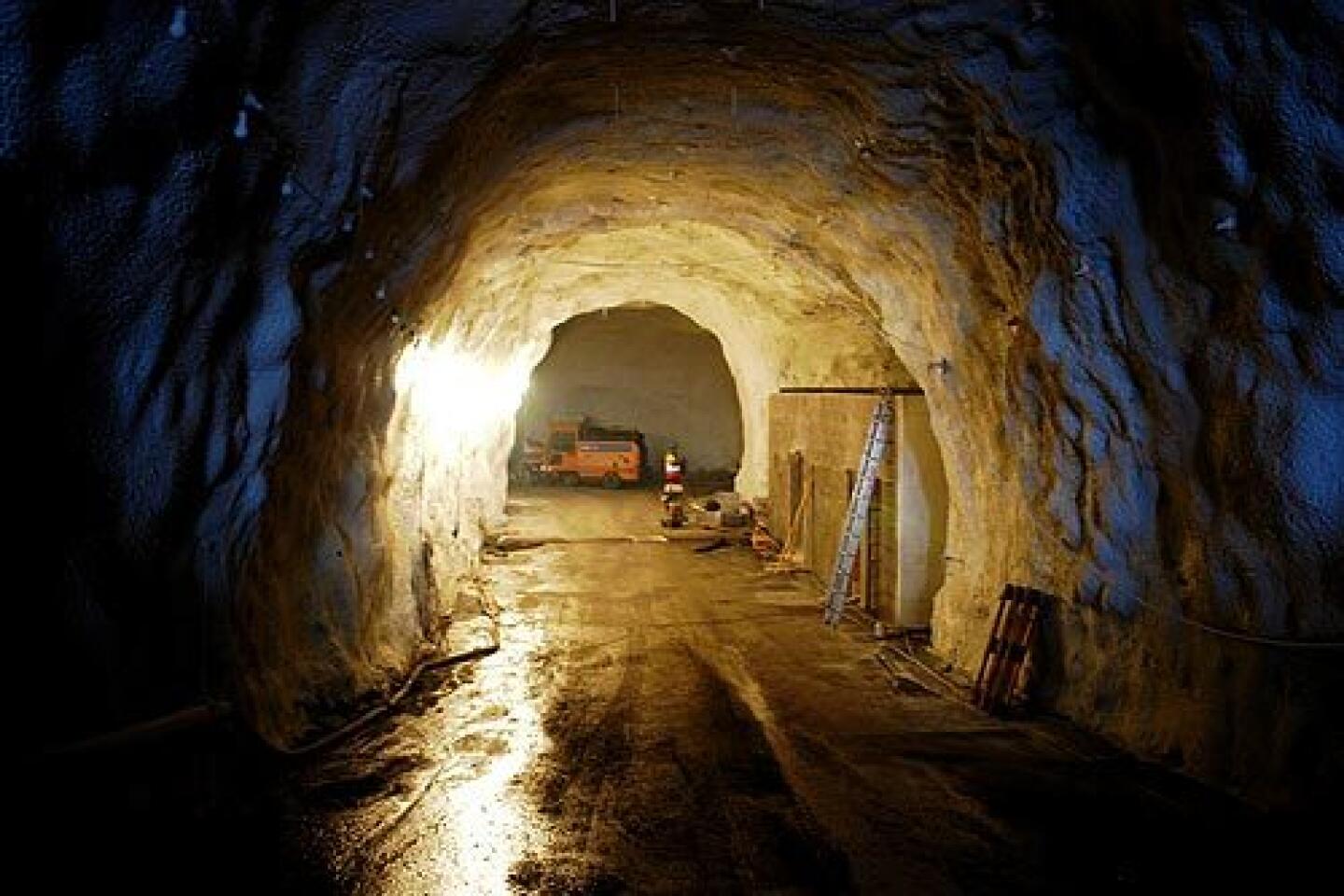

LONGYEARBYEN, NORWAY — High above the icy fjord, the vault is almost complete. Inside a frozen mountain not far from the North Pole, workers are building three concrete chambers to withstand global warming, floods and fires, wars and nuclear holocaust.

This Arctic safe, nicknamed the “doomsday vault,” will protect millions of crop seeds here on the forbidding Svalbard archipelago, the northernmost inhabited spot on the planet. The survival of Earth’s agriculture is being entrusted to a land inhospitable to life, where only the toughest plants, animals and humans endure.

At the entrance to the vault, visitors can see glaciers and frozen wilderness shimmering in the distance. Should the bleakest global warming scenario come true -- a total meltdown of Antarctica and the Arctic, swamping the planet as sea levels rise -- the seeds would be sheltered in their cave here, 400 feet above the Advent Fjord.

In case of an electricity blackout, the permafrost ensures that the seeds would remain refrigerated in the state-of-the-art Svalbard Global Seed Vault. Recalling the opening scene of the old “Get Smart” television show, airlocks, steel-reinforced doors and a video-monitoring system operated from Sweden hundreds of miles awayare designed to protect the $6-million vault deep inside the mountain.

National seed banks around the world might be devastated by natural disasters or raided in a war, but the remoteness of the Svalbard vault makes it the ultimate safety backup.

“This is a library of life,” said Cary Fowler, director of the Global Crop Diversity Trust, an international foundation that protects the world’s crop seeds. “We’ll be taking the knowledge embodied in these genes to fashion new solutions.”

Agriculture continually has to adapt to the changing conditions on the planet, be they climate shifts, new pests and diseases, or increasing demand for food as the world’s population grows. Earth’s biological diversity, however, is facing its worst threat in centuries, brought on by more aggressive farming methods, environmental degradation and changing weather patterns.

In the last century, as much as 75% of the genetic diversity -- hundreds of thousands of plant varieties -- has been lost, according to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization. Every day, another plant variety becomes extinct.

“We have a giant puzzle unfolding here,” Fowler said. “We don’t know what the picture is going to be, so we don’t need to be throwing away the pieces, especially when it’s so cheap to conserve them and so expensive to lose them.”

Geography is security.

The vault’s location on this rugged cluster of islands between the 76th and 81st parallels has been carefully chosen. Fewer than 3,000 settlers, mostly Norwegians and Russians, live in the Arctic archipelago governed by Norway. With rare exceptions, there are no births on the islands -- there are no social services and only limited healthcare -- and those who settle are mostly young and physically fit.

These days, the burgeoning tourism industry fuels the economy of tiny Longyearbyen, but historically it has been a mining town, and hundreds still labor in the coal pits.

During the 1960s and ‘70s, the Soviet Union built up a solid presence on Svalbard, which can be mined by all 40 signatories to a 1920 international treaty. But with the demise of the Cold War, it withdrew.

Pyramiden, a Soviet-model mining town farther up the Advent Fjord, has been meticulously preserved. On the walls of the barracks where the Soviet workers lived, yellowing photographs bear witness to their harsh life. Lenin’s statue still stands on the main square of this ghost town, facing east.

On Svalbard, the rugged life in the mines is giving way to an orderly life of the mind. The scientists are taking over.

A small, newly built university campus in Longyearbyen offers undergraduate courses in Arctic biology, geology, geophysics and technology. It’s not uncommon to see undergraduate students, wrapped in many layers of clothing and carrying rifles, setting out toward the mountains for research trips in the tundra.

Because of the threat of polar bears, everyone leaving downtown Longyearbyen is required to carry a rifle. Still, every few years, someone is killed by a bear in the vicinity. Everyone in Longyearbyen has a polar bear story -- often told with Norwegian understatement -- about an encounter with one of the fearsome animals. With the brutally cold winters here, people don’t blink when they see someone inside the small bank wearing a ski mask and carrying a gun.

This rugged frontier attracts a tough, self-sufficient bunch difficult to impress with tales of adventure and physical prowess.

Mark Van de Weg, a Dutch sailor and boat builder, makes his living transporting scientists and other travelers around the fjords in Jonathan III, a sailboat he built. He began coming to Greenland and Svalbard in 1994 after circumnavigating the world in a traditional wooden sailboat. Five years ago, he wintered with his girlfriend and two guard dogs on a small sailboat stuck in the ice of a remote fjord.

“You come home from a three-week [expedition], and maybe you talk about it for 10 minutes,” he said. But people in the community also look out for one another. You won’t be allowed to sit alone at home during Christmas, he said.

The isolation combined with the vigilance of the residents makes Svalbard a good location for the seed bank. It’s difficult to arrive or leave unnoticed.

On most days, there is a single flight from mainland Norway to Longyearbyen, transporting people and all food supplies. Occasionally, icebreakers arrive from Russia and Norway. Cars are limited to Longyearbyen. There are no roads outside town, so moving around must be done by boat, on skis, by dog sleds or on snowmobiles.

Many tourists come to experience the peculiar seasonal phenomena of the Arctic. During the short summer, the sun never sets. During the winter, the islands are enveloped in unbroken darkness. Visitors can also see the northern lights, the near-mystical green-hued illumination of the sky also known as aurora borealis.

Some travelers use Svalbard as a jumping-off point for expeditions to the North Pole, about 800 miles to the north. Others explore the fjords, experiencing wildlife, glaciers and the array of colors produced by the freezing water and ever-changing ice.

Like calligraphy traced on a vast frozen canvas, eiders and arctic terns paint intricate patterns of flight against the backdrop of bright-blue glacier fronts. Beneath them, puffins and seals frolic in the water or rest on floating bits of ice. On land, white arctic foxes and polar bears hunt for prey.

Solitary wooden cabins stand abandoned in the wilderness, totems summoning memories of expeditions ending in madness and death, humans crushed by nature.

Above Longyearbyen, workers laboring in the cold have blasted through the mountain, carving out the vault intended to conserve specimens of all the known agricultural seed varieties in the world.

“Svalbard offers a low-cost, safety backup -- it’s a great solution to the problem,” said Luigi Guarino, a senior science coordinator at the Global Crop Diversity Trust, which is funded in part by a $30-million grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

But the vault also has symbolic importance, he said. “To have the agreement to have all this material in one place sends an important message: We’re trying to work together to safeguard the world’s agriculture.”

Although the Norwegian government has paid for the vault’s construction, the trust will operate it and underwrite day-to-day operations amounting to a projected $125,000 per year. The trust also will help developing countries get their seeds to the Arctic. It’s a delicate operation: Scientists have to transport the seeds quickly in special envelopes inside sturdy boxes to protect them against decay.

The seed vault will be a bank of sorts. In case of a local, or a global, disaster, countries can retrieve indigenous seeds to reestablish their native agriculture.

Some calamities, such as war or flooding, are sudden, but others take place over time. Scientists believe that climate change will bring more extreme weather, flooding some areas and drying others. Consequently, farmers and scientists will be forced to grow new varieties or entirely novel kinds of crops.

“Although it is easy to assume that U.S. agriculture is relatively self-sufficient, all agriculture in today’s world is interdependent,” concludes a report published in 2005 by the University of California Genetic Resources Conservation Program, based at UC Davis. “Crop diversity collections are the linchpin of this interdependence, and thus central . . . to the future of U.S. agriculture.”

International seed banks returned indigenous varieties of rice to Cambodia after the Khmer Rouge’s failed agricultural policies three decades ago threatened to destroy the country’s rice production. Local bean varieties were salvaged in Rwanda after the 1994 genocide because of joint efforts by local and international researchers. The crop has helped revive the country’s agriculture.

After the Indian Ocean tsunami caused devastation in South Asia in 2004, international seed banks provided Malaysia and Sri Lanka with rice varieties that could thrive in the coastal regions where large amounts of salt had been deposited by the surging seawater, according to the UC report.

“What we’re trying to do is an insurance policy,” Guarino said. “We don’t know if those seeds are going to become important next year or in a hundred years.”

Some scientists involved with crop conservation, however, are less enthusiastic about the Svalbard project, which they believe could take funds away from other initiatives.

“The problem that we have with this much-publicized project is that it tends to divert attention, energy and money away from what we consider as much more urgent and sustainable efforts to save biodiversity on the farm,” said Henk Hobbelink, director of GRAIN, a nongovernmental organization based in Spain that promotes agricultural biodiversity.

More attention and funds need to be directed to farmers because their knowledge, practices and genetic resources continue the process of crop evolution, said Stephen Brush, a professor in the department of human and community development at UC Davis.

“I would never say, do away with gene banks. But we must be wary of thinking that gene banks are the solution to the agricultural future of the world,” Brush said. “Of course, if there’s something like a nuclear war that kills the world’s crop plants, we certainly want to have the gene bank in Norway, but under normal circumstances, gene banks are just part of the larger picture.”

Many countries have their own crop repositories or seed banks. There are more than 1,400 worldwide, holding about 6.5 million plant samples. At the federal gene bank in Fort Collins, Colo., scientists store plant tissues in liquid nitrogen baths at minus-213 degrees, inside high-tech cold rooms.

But many of the world’s gene banks are plagued by funding shortages, management failures and equipment problems. In the southeastern African nation of Malawi, the national seed bank consists of a chest freezer in a shack.

In Afghanistan, Taliban fighters destroyed the national seed bank in 2002. The following year, looters ruined Iraq’s national seed repository. But Iraqi scientists had smuggled a “black box” of plant samples across the border to Syria to safeguard them before the U.S.-led invasion that March, and Iraqi farmers today can replant their fields with indigenous crops.

The only seeds that will not be accepted for storage at the Svalbard vault are those from genetically modified plants.

As its first priority, the trust has identified “at-risk collections,” from countries that have material not duplicated in any of the international seed banks. Some contain samples that will die unless they are regenerated within the next few years.

The seeds constitute a living legacy, the trust’s Fowler said.

“If we are going to survive as a species, it will be because we’ve learned to share that heritage,” he said. “I know this is just a cave in a mountain, but it’s also the only thing I can think of that is really tangible, positive and directed toward the future with virtually all the countries working together. Maybe there’s a lesson in that.”

Comments? Email [email protected]

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.