Guided guerrilla tours explore a unique side of El Salvador

Perquin, El Salvador — EFRAIN Perez moves with a slight shuffle as he escorts visitors through the Museum of the Salvadoran Revolution. His halting gait, the result of bomb shrapnel that nearly pierced his brain, has slowed the 38-year-old ex-guerrilla’s body, but not his mind.

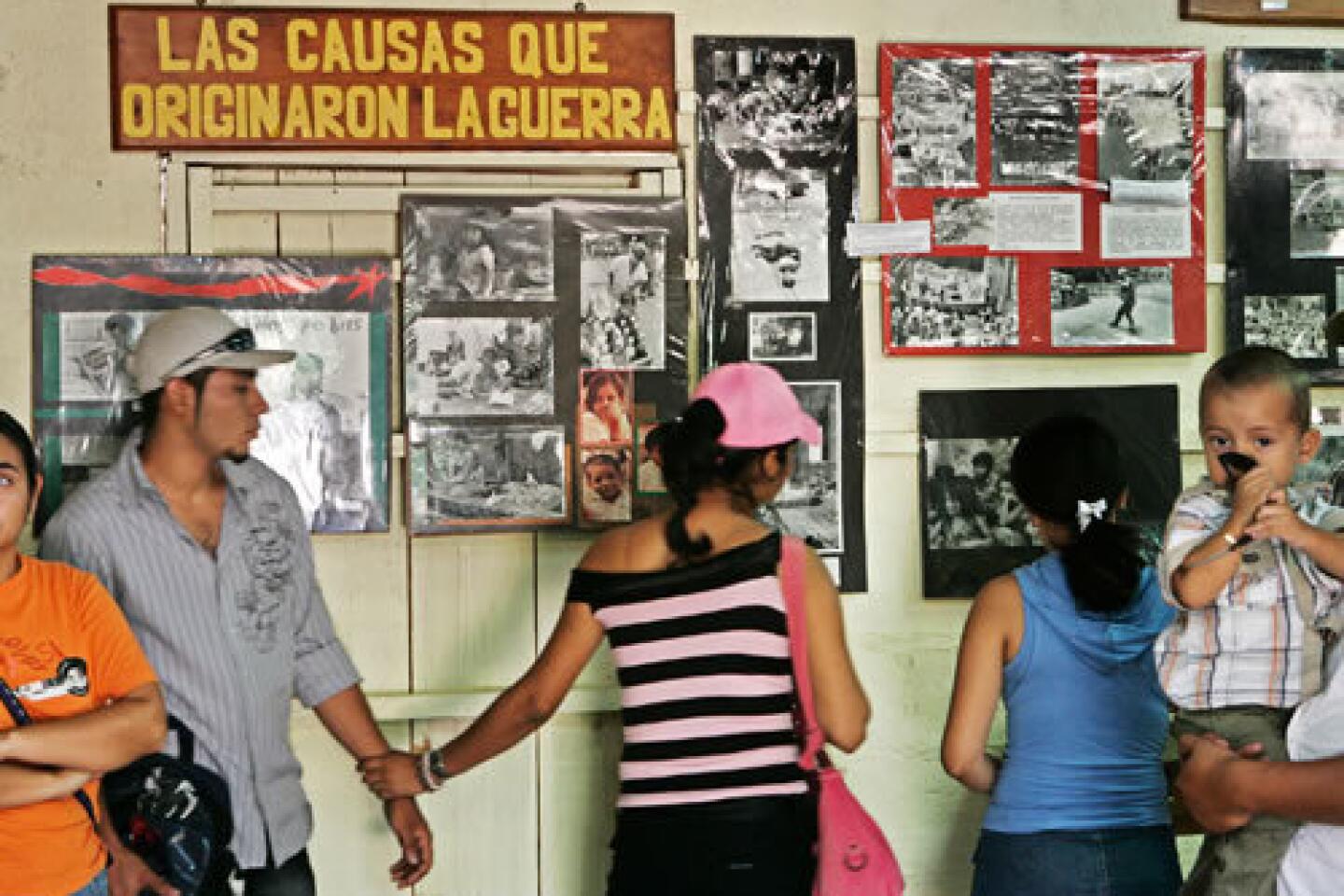

Effortlessly, he rattles off the dates of battles and assassinations, lists the names of obliterated villages and fallen comrades in arms. Then he leads his guests through narrow rooms filled with propaganda posters, Soviet-era surface-to-air missile launchers and dozens of grainy black-and-white photos of the “heroes and martyrs” who died in a brutal conflict that already has slipped into history’s shadows.

“When you live it, when you know the consequences, it sticks in your mind. You don’t forget,” said Perez, a soft-spoken man who became a Marxist guerrilla after his mother, father and brother were killed by army soldiers near the start of El Salvador’s 12-year civil war in the early 1980s. He was 11.

Under other circumstances, the musty artifacts on display at the museum, a one-story tin-roofed building perched on a muddy hillside, might have been stashed away in private homes or left to rust in some abandoned jungle lair. Perez might have frittered away his days among El Salvador’s legions of unemployed.

But today he and a number of his fellow former rebels have a surprising new profession: tour guide.

While El Salvador’s tourism ministry labors to attract conventioneers to the capital and sun worshipers to Pacific beach resorts, many former guerrillas, as well as ordinary civilians whose lives were forever changed by the war, are developing an “alternative tourism.”

Since peace accords were signed in 1992, thousands of curious visitors from across Latin America, Europe, the United States and Canada have been drawn to this remote mountain village 10 miles from the Honduran border and other sites scattered across this violence-haunted republic of 6.9 million. While some visitors are sympathetic to the former rebels’ cause, others seem simply interested in the history.

Centered on quarter-century-old killing fields and onetime rebel camps, turismo alternativo has brought vanloads of day-trippers to a handful of isolated villages linked to the struggle that claimed 75,000 lives and left 8,000 people missing.

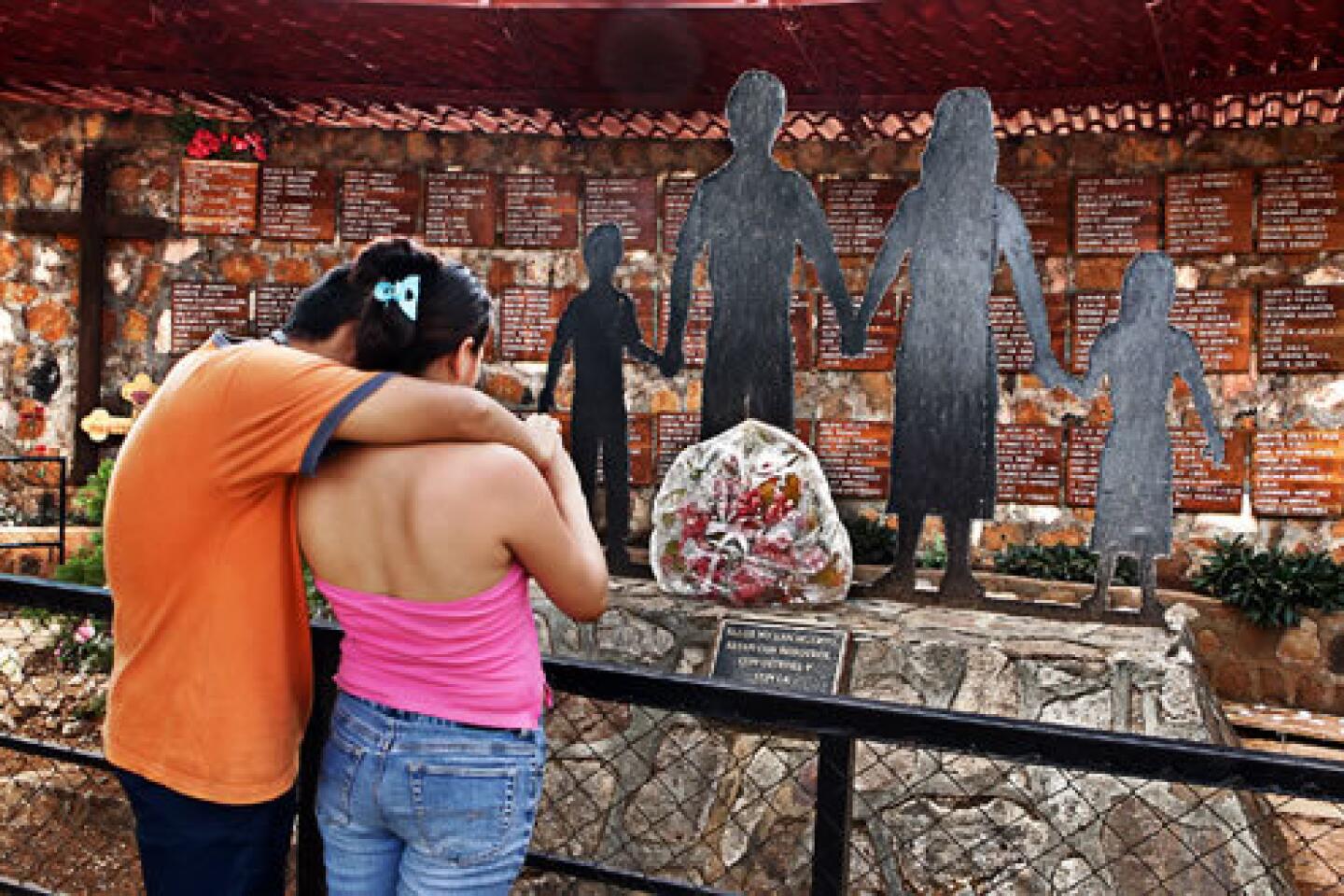

Among the most infamous is El Mozote, a rural hamlet where as many as 900 men, women and children were raped, tortured and massacred by government troops on Dec. 11, 1981.

“There’s a new generation that’s realizing the history of Salvador,” Perez said. “Always there’s an ignorance, of not knowing anything, and we have to change the mentality.”

Be it Gettysburg or the underground tunnel networks used by the Viet Cong, war-related tourism has become a worldwide enterprise.

What’s unusual about El Salvador is that many of its sites are being operated not by the federal government but by its former enemies, the ex-combatants of the Farabundo Marti National Liberation Front, or FMLN, a coalition of communist and other leftist forces.

The country’s Tourism Ministry doesn’t support the sites and said that, while not ignoring the war years, it has other priorities right now. “The war, lamentably, is part of our history,” said Minister Jose Ruben Rochi. “We can’t forget what happened in the decade of the 1980s.” However, he said, Salvadoran tourism is still in a “pretty initial, pretty elemental” stage.

LIKE many Salvadorans, Francisco Armando, 26, and Carlos Pineda, 25, weren’t even born when the civil war erupted. They remember the swirling sound of helicopters overhead and the fear they felt as youngsters watching soldiers march through the streets, but not much else.

Earlier this month, the men and their families visited the museum here for the first time after a 4 1/2 -hour trek from their home in Sonsonate. Strolling the museum, Armando compared its artifacts with a documentary about the war that he had downloaded onto his cellphone.

Previously, he said, all his impressions of the era came from movies.

The museum’s “reality was much stronger,” said Armando, a public health worker.

The guides, all ex-guerrillas, work six days a week from 6 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. Admission is 60 cents for Salvadorans and $1.20 for foreigners, plus $1 for parking. The compound includes a small store that sells snacks, Che Guevara T-shirts and books about Archbishop Oscar Romero, the antiwar cleric who was assassinated by government agents while celebrating Mass in 1980.

During holiday periods, such as Holy Week, as many as 6,000 people may visit the museum.

Plans call for adding a 100-seat conference room and theater, one of whose functions would be to host gatherings of families trying to locate missing relatives.

A few days ago, two Los Angeles-born cousins, Tanya Rubio, 21, and Katherine Rubio, 16, were visiting the museum as part of a weeklong trip to their families’ home country. Exploring the civil war’s history, they said, was part of reconnecting with their heritage.

“My American friends don’t know what happened here,” said Tanya Rubio, studying an army helicopter’s mangled remains. “I explain it to them.”

Two other Americans, Brendan Fischer, 25, a Peace Corps volunteer, and his sister Katie, 22, a Wisconsin journalism student, were also visiting. Earlier in the day, the siblings had gone to El Mozote, about 40 minutes away. The massacre carried out there by the Atlacatl Battalion initially was denied by both the Salvadoran government and the Reagan administration, which supported the regime. It wasn’t until the early 1990s that forensic investigations and a report by the United Nations-sanctioned Truth Commission determined that the slaughter had occurred.

Today, El Mozote is a hamlet of about 65 families, said Gumercindo Claros, coordinator of the Tourist Committee of Mozote and one of six guides who offer free tours of the area. Sites include the churchyard “Garden of the Innocents,” where 146 children lie buried, and the spot where Rufina Amaya, one of a handful of known survivors, hid behind a tree and escaped.

Amaya died of a stroke March 6 of this year, but what she witnessed that day in December 1981 has been passed on to other storytellers. “We talked a lot, always,” Claros said.

THE most striking and least accessible of the war-related sites can be found above the mountain hamlet of La Montanona in Chalatenango province. The entrance to the former rebel base begins where cows wander freely and electricity lines have yet to arrive. Outside the schoolhouse hang the remains of an army bomb that’s now used as a bell.

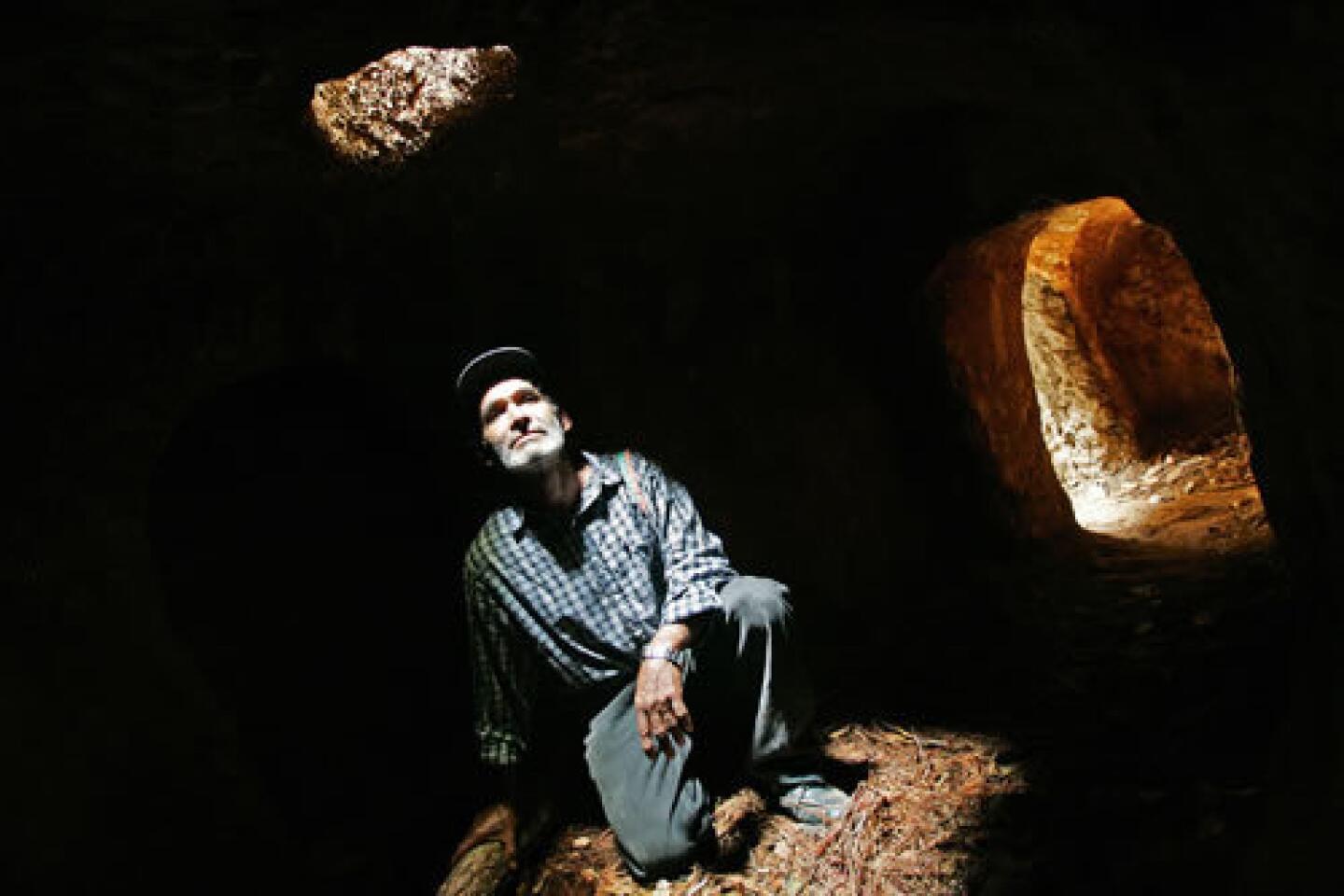

About 150 people had visited the site this year as of Easter Sunday, said Fidel Castro Santos, 60, an ex-combatant who now works as the site’s “forest keeper.” Admission is $1 per person, and $3 to camp.

The ex-rebels who supervise the site have built railed wooden walkways and picnic tables along the tour trails and said they are trying to develop a forest management plan to protect natural resources.

Castro said the alternative war tourist industry has arisen despite the lack of a central coordinating authority, or any formal connection among the ex-guerrillas at the various sites. “Clearly, we have the same sentiments and the same stories, but there is no contact.”

Scrambling down a hillside, Castro directed his visitors to one of the rebels’ former makeshift “hospitals,” dug deep into the clay cliffs to withstand bombing raids. Another 100 yards up the road there’s a crude wooden shelter where Radio Farabundo Marti used to broadcast.

A network of tunnels crisscrosses the hillside, where the remains of a guerrilla were found at the bottom of a ravine last year, his papers still intact and his Seiko watch still working.

Castro strolled up the crest of another hill to a wooden platform propped on stilts, about a dozen feet above the ground. The late-afternoon view was breathtaking: a shimmering lake offset by volcanic peaks. Where bombs and mortars once rained constantly, the only sound was the breeze drifting through cathedral-like stands of pines.

Like many of his compas, or comrades, Castro was moved to support the guerrilla cause not by reading Marx or Mao but by his immersion in liberation theology, the radical Roman Catholic doctrine that flowered in Latin America during the 1960s and ‘70s and justified revolutionary action as a means of opposing entrenched social inequality.

One of Castro’s mentors was Archbishop Romero, whom he knew personally. In their youth, Castro said, he and his colleagues thought that God was in heaven. “But we were mistaken. God is in everyone and everything,” he said, resuming his walk through the forest.

With rising levels of drug trafficking and gang violence, and a shaky economy that relies heavily on remittances sent home by the 655,000 Salvadoran immigrants living in the United States, including 187,000 in Los Angeles County (according to 2000 U.S. census figures), El Salvador could use any financial boost.

Though he predicts that no upper-class Salvadorans will visit the new war-related sites, Leonel Gomez, a political scientist who helped broker peace talks between the rebels and the U.S. government, believes that “tourism here could provide jobs for a lot of people.”

“It’s amazing that an ex-guerrilla will start something, anything,” Gomez said. “I don’t know where in the hell they get the strength. Because nobody’s helping them very much.”

It’s unclear how much interest the war-related sites will generate as the conflict fades, because the passions that enflamed the war still burn.

The right-leaning Arena party controls the presidency and, with its political allies, holds a majority in the federal legislature. But the FMLN political party, descended from the rebel organization, can block legislation requiring a two-thirds majority. Both major parties already are gearing up for the 2009 national elections, a spectacle that one Salvadoran economist recently likened to awaiting a double train wreck.

Meanwhile, the war’s physical scars endure. One of the deepest can be found along the road between San Salvador and the hilly Guazapa region, a former guerrilla stronghold 20 miles from the capital. One section is lined with bombed-out houses and a shattered colonial-era church resembling the Alamo.

A couple of miles down the road lies the picturesque town of Suchitoto. Geraldo Suarez, 64, is one of 10 former rebels who last year opened a bar and small hostel in a rehabilitated mansion that once belonged to a prominent military family. Sitting in the bar’s tranquil courtyard, lined with mango and avocado trees, Suarez, a former communications specialist, said that restoring a damaged building is much easier than restoring a people’s historical memory.

“What is it we want to reconstruct? It’s like deciding on a screenplay for a movie,” he said. “All the great actors want to be in this great movie. And now it’s harder because many of the actors are dead.”

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.