In Vienna, time for creating new memories and revisiting the old

Reporting from Vienna — “How do you think you’re like your parents?” Carl asked me over the whoosh of water spouts as we lay on lounge chairs by an enormous indoor pool.

Sunday morning in Vienna was gray and drizzly, and the Therme Wien, on the city’s outskirts, was crowded with children squealing under the spa’s water fountains and older folks settling achy joints against the warm jets in the main pool.

“Good question, cousin,” I replied. “I’m probably like them in ways that give me pleasure and in other ways that make me cringe,” I responded after some thought. “What about you?”

The questions — his and mine — were part of our plan: four days together in Vienna with few plans except time to talk. Really talk.

What better place for meandering conversations about life, family and our hopes and fears than this immaculate Viennese spa on a cold October day?

Although Facebook and FaceTime easily connect us with friends and relatives, for many of us baby boomers, spending time with those we hold dear — real, not virtual, time — has grown more important as those proverbial grains of sand keep falling.

It certainly has to me, and my cousin Carl is among the dearest.

Because he grew up in New York City and I in L.A., we saw each other rarely when we were children. Distance plus our seven-year age difference meant we weren’t close until recent decades.

Carl moved to Amsterdam in 2005 to marry a lovely Dutch man whose disposition is a buoyant counterpoint to our family’s brooding nature. In the years since, most of our visits have been brief and sometimes centered on family memorial services or weddings.

Somewhere along the line we began to email regularly, long disquisitions on books, family lore, our worries and concerns. IPhones (we were each late adopters) turbocharged our relationship; we now text every few days and FaceTime regularly.

But the more contact we had, the more we seemed to want, especially extended time, with no memorial services to attend.

In good company?

We chose Vienna because we both loved the city — who doesn’t? Because we had each done the “must-do’s” on previous trips, we set just a few priorities for our time together: good food, some music, a spa visit, some time apart and whatever else struck our fancy. The trip would be an experiment for us both.

Carl, who knows Vienna far better than I, booked many of our reservations because I can be passive and indecisive to the point of exasperating when it comes to travel. Truth is, I’m happy to do whatever as long as the company is good. And I was pretty sure it would be.

Still, I had doubts, as I’m sure he did. Would four days be too much togetherness? Would one of us withdraw or grow moody? Would we trip old family landmines?

I also had invited my closest German friend to join us for part of the time so I worried whether the threesome would jell.

But once I saw Carl, who had sweetly insisted on meeting me at the Vienna airport, I knew we’d be fine.

“I’m so glad you came,” he said, hugging me tightly as I came off the plane.

Emotionally nourishing

Dinner our first night was at Gasthaus Poschl, a tiny, homey restaurant in the heart of the old city that Carl had visited on previous trips.

We lingered for two hours over, for me, divine rice pilaf and pumpkin soup so delicious I ordered it again my last night in Vienna.

Our dinner conversation quickly dived deep: marriage (his and mine), children (mine) and the “are-you-happy?” check. It felt emotionally nourishing to me.

On the stroll back to our pension, Carl slipped his arm through mine.

My friend arrived the next day, and the three of us had tickets for Mozart’s Requiem that evening. The 18th century piece is performed every Saturday from April through October in the floridly Baroque St. Charles Church.

The “Requiem” is a Vienna institution, and although the performance was so-so, according to my musically knowledgeable cousin, it was a pleasant way to spend the evening.

For me, the day Carl and I spent at the Therme Wien was a highlight of our time together. The spa, a five-minute ride on the U1 subway line from central Vienna, is one of the largest thermal springs in Austria, with multiple pools, sauna and steam rooms, a cafeteria and rows of chaise longues.

Carl and I had visited a similar spa in Cologne, Germany, a few years before, and I had loved the indulgence of hours with nothing to do but soak and talk.

In Vienna, we grabbed chaises and laid out our spa towels along with our plans for the coming year: a possible new venture for Carl, a concerted effort by me to kick back a bit. And more reminiscences of our now-long-passed parents.

This indulgence was affordable: I spent about $35 for the day, including lunch in the spa cafeteria.

See the world

Another highlight of our four days was the Globe Museum, a one-of-a-kind collection with about 470 globes and related objects dating to the mid-16th century. We had the place to ourselves on a quiet Monday.

We also toured the Jewish Museum Vienna, founded in 1895 as the oldest Jewish museum in the world, closed by the Nazis in 1938 and reopened in 1988, with items charting Jewish history from medieval times and, when we visited, an exhibit about Elvis Presley’s Jewish secretary.

One afternoon, we took in the 1949 classic thriller “The Third Man,” with Joseph Cotten and Orson Welles. This classic, filmed on Vienna’s post-war streets and in its sewers, has played for years at the Burg Kino, like the “Rocky Horror Picture Show” at West L.A.’s Nuart Theatre.

Long ambles took us into the sprawling, open-air Naschmarkt with its food stalls and piles of schmattas, past the treasure-trove of elegant Art Nouveau buildings and through the city’s many parks.

The night before my friend returned to Munich, the three of us headed to Schnitzelwirt, for Vienna’s typical breaded and fried veal steak.

The restaurant is a 40-year-old mix of tradition and kitsch where waitresses wear dirndls and bar stools rest on faux lederhosen-clad legs.

The schnitzel was perfectly done, and the fried-meat aroma saturated my clothes, another nice memory when I unzipped my suitcase back in L.A.

Although our Vienna meet-up was a great success, some things didn’t work. Our pension was centrally located but dingy, and the hot water unreliable. And including my friend was not fair to her or to Carl. While we spent some time as a threesome and did other things in pairs, I was torn between them and anxious about whether they enjoyed one another.

But overall, I treasure those days in Vienna with Carl, and I think he feels the same. The experiment was a success. Social media links us together in ways that were once unimaginable to us boomers. But it doesn’t replace time together, time to draw on common memories and create new ones.

Perhaps the best verdict about our trip is that before we parted, Carl and I vowed to meet again somewhere this fall — and we are.

18 exhibits celebrate Vienna’s role in the birth of Modernism

Vienna gave birth to the turn-of-the-20th-century Modernism movement, the subject of 18 exhibits on view this year throughout the city.

Modernism, often known as the Secession Movement, Art Nouveau or Jugendstil, flowered in architecture and the visual arts as well as in literature, philosophy, political thought and music.

Between 1890 and the start of World War I, Vienna was a melting pot of creativity. The Viennese Modernism movement, radical for its time, emerged in reaction to the conservatism of the fading Habsburg age.

The exhibits celebrate the enduring achievements of four of Modernism’s leading lights, who all died in 1918: artists Gustav Klimt, Egon Schiele and Koloman Moser, along with architect Otto Wagner. Each man profoundly shaped turn-of-the-century Vienna and the city as it remains today.

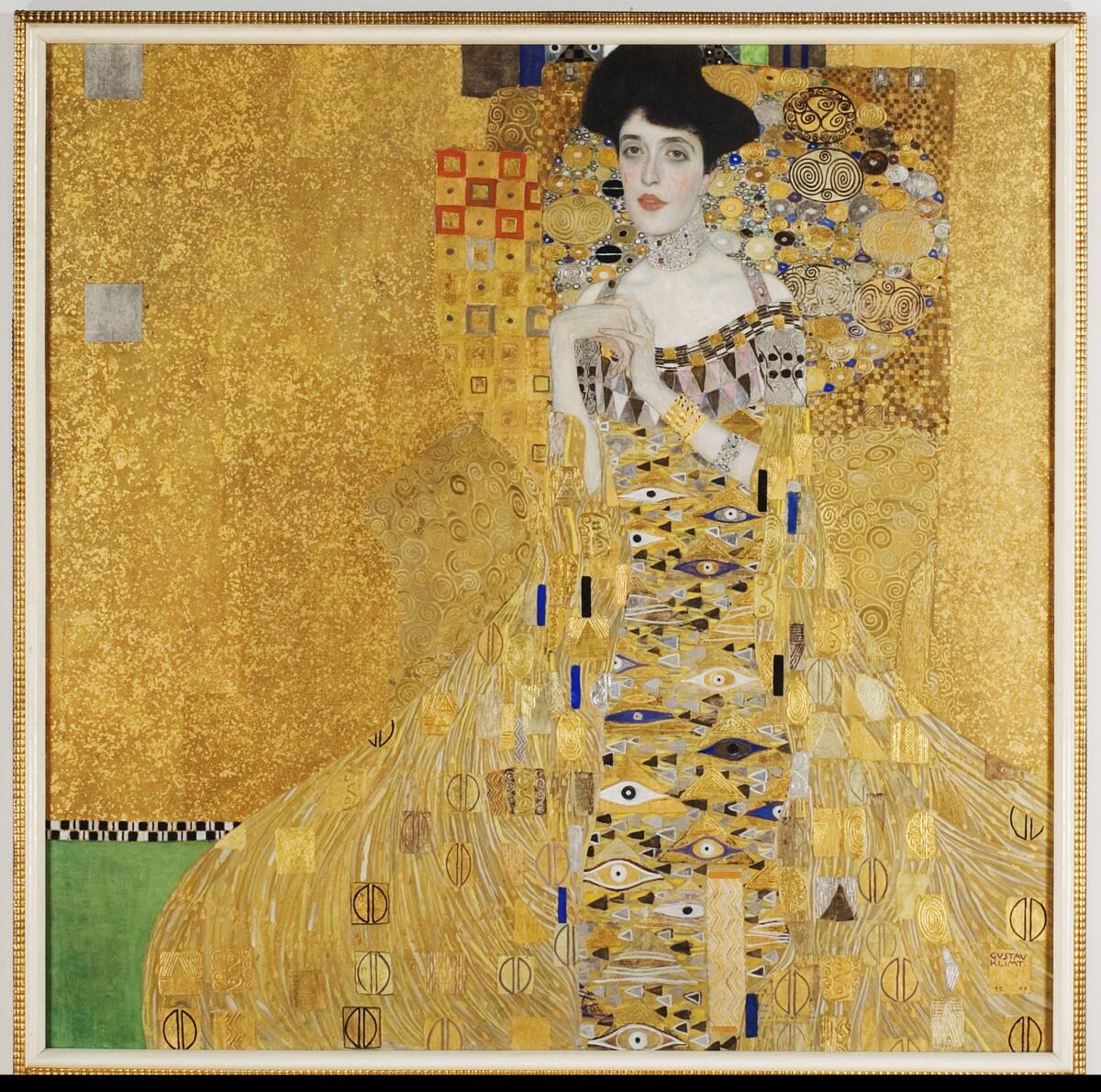

Klimt is perhaps best known here for his 1907 portrait “Adele Bloch-Bauer I” (also called the “Woman in Gold”), on view in New York’s Neue Galerie.

Klimt was a painter, draftsman, mentor and leading figure of the Vienna art and architecture scene. His paintings, including “The Kiss” and “Death and Life,” break representational forms into tiny, glittering pieces, and his erotic style, daring for the time, made his work controversial.

The works of Schiele, one of Klimt’s protégés, is noted for its raw intensity, stark nudity and the jerky poses of his subjects. (Some portraits remain so controversial that cheeky posters for the Modernism exhibit cover nude midsections with banners daring visitors to “See it all in Vienna.”)

Schiele’s twisted body shapes and expressive lines also mark him as one of the early lights of the early 20th century Expressionism school.

Schiele died at age 28 when the Spanish flu pandemic, which may have claimed more than 2 million lives in Europe, reached Vienna. His pregnant wife had succumbed three days earlier to the same disease.

Wagner changed the face of Vienna. He was a founding member of Vienna Secession, the revolutionary artists’ association, and his buildings celebrate the beauty of simplicity, a dramatic departure from the prevailing fussy and frothy style.

A century later, the Karlsplatz Pavillion, the Austrian Postal Savings Bank, apartment buildings such as the Majolikahaus and several subway stations, still look contemporary and daring. Wagner’s followers incorporated his penchant for simplicity along with forms and lines from nature into furnishings and jewelry.

One of those, Koloman Moser, focused on functional objects and graphic design, producing an astonishing portfolio of books and graphic works, including postage stamps, fashion, stained glass windows, ceramics, blown glass, tableware, silver, tapestries, jewelry and furniture.

Like his fellow Secessionists, Moser emphasized clean lines as a reaction to the Baroque excess of his surroundings, but he also incorporated repetitive motifs of classical Greek and Roman art and architecture.

For more information on the Modernism exhibits, the artists and their times, visit Vienna 2018 exhibitions and Viennese Modernism 2018

If you go

THE BEST WAY TO VIENNA

From LAX, From LAX, Austrian offers nonstop service to Vienna, and Air France, KLM, Lufthansa, Swiss, LOT, Iberia, British and Turkish offer connecting service (change of planes). Restricted round-trip airfare from $1,114, including taxes and fees.

TELEPHONES

To call the numbers below from the United States, dial 011 (the international calling code), 43 (the country code for Austria), 1 (the city code for Vienna) and the local number.

WHERE TO STAY

Hotel Beethoven Vienna, 6 Papagenogasse, Vienna; 58-74-48-20. Family-owned and operated four-star hotel with walking distance of museums and the Stadtpark. Doubles from $200, including breakfast.

Hotel Zipser, 49 Lange Gasse, Vienna; 40-45-40. Rooms and private apartments, some with balconies. The Art Nouveau hotel is tucked away on a side street a 10-minute walk to the Ringstrasse. Doubles from $150 with breakfast.

Leonardo Hotel Vienna, 6-8 Matrosengasse, Vienna; 59-90-10. A bit outside the city center but a great value—a short walk to transit where a 5-minute ride will get you to the major sites. Doubles from $90 with breakfast.

WHERE TO EAT

Gasthaus Poschl, 17 Weihburggasse, Vienna; 51-35-288. Warm, low-key bistro with excellent seasonal and traditional Viennese dishes. Reservations recommended. Cash only. Main dishes $15-$30.

Schnitzelwirt, 52 Neubaugasse, Vienna; 523-37-71. The pounded, breaded and fried veal dish is expertly done. Add potato salad, fries or a green salad and, of course, beer for a traditional Viennese meal. Adventurous eaters might try the schnitzel a la Mexico (rolled meat filled with paprika, mushrooms and ham). Main dishes from $10.

Café Prückel, 24 Stubenring (Luegerplatz); 512-61-15-12. This classic Viennese coffee house and restaurant opened its doors in 1904. Racks of newspapers and live piano music (some days) encourage customers to linger.

TO LEARN MORE

Austrian National Tourist Office

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.