Titanic: For many victims, their final resting place is in Halifax, Canada

Halifax, Canada — A cold wind ripped through Fairview Lawn Cemetery. Then came the frigid rain. In a minute, I was thinking, the headstones will be shivering.

“Now,” said Blair Beed, my guide, “imagine how it would have been in those lifeboats. Surrounded by ice.”

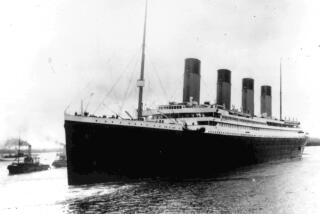

He was talking about the Titanic, of course. Although this Halifax cemetery lies about 750 miles northwest of the waters where that celebrated ship went down April 15, 1912, it was the seamen of Halifax who retrieved more than 300 of the dead, along with a grim harvest of flotsam. In the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic downtown, you can see the lost gloves of a doomed millionaire and the lost shoes of a tiny child. Fairview Lawn Cemetery is home to 121 Titanic victims, more than you’ll find anywhere else above sea level.

This city (population: about 390,000) gets plenty of attention in Canada for its role as a port, a provincial capital and a college town, with no fewer than five universities, whose students rarely see a week without rain. The local pro basketball team is called “The Rainmen.”

Halifax is about 45 minutes’ drive from Peggy’s Cove, where one of Canada’s most picturesque lighthouses towers over a glacier-scraped granite shore, and about 60 minutes from Lunenberg, one of Canada’s most picturesque fishing villages. Halifax’s star-shaped hilltop citadel, where forts have stood since the 18th century, draws legions of summertime tourists. The Canadian Museum of Immigration stands on the city’s Pier 21.

But never mind that. I came for Titanica.

My first stop was the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic, waterfront repository of the man’s gloves and the baby shoes—preserved despite orders to thwart souvenir-hunters and burn victims’ clothing.

Even in this centennial year, the Titanic occupies only part of the museum’s exhibition space, because Halifax’s maritime history is a long story. (Samuel Cunard, the shipping magnate and founder of Cunard Line, was born here.) But the museum’s upstairs Titanic display offers plenty, including a Titanic deck chair (plucked from the water, given to a local clergyman and used in his backyard for decades) and a cribbage board and rolling pin (both carved from Titanic wreckage following the longstanding custom of recycling wreck wood). Tying them together, of course, is a detailed accounting of the ship, the officers, crew and passengers, the iceberg, the sinking and the local angle.

While the passenger ship Carpathia was scooping up and delivering Titanic’s 700 or so survivors to New York, Halifax was getting ready for the dead. At the behest of the White Star Line, owner of the Titanic, Halifax’s Mackay-Bennett — usually a cable ship used for laying and maintaining transatlantic telegraph cables — set off to collect victims, with a clergyman as well as embalmer John Snow among those aboard.

Eventually three other ships were dispatched as well, but the Mackay-Bennett arrived at the Titanic’s coordinates first and found more than 300 bodies, buried some at sea and brought back the rest.

“The Death Ship Will Arrive at Noon,” announces one of the old headlines on display.

Through Nov. 4, the Maritime Museum is offering a temporary exhibit on the Titanic, cable ships and how telegraph operators served as a “Victorian Internet,” passing along disaster news. And for the foreseeable future, the museum will be showing off a new Titanic model, 62 inches long, mostly pine and basswood, which was getting touches from volunteers John Green and Gerald Wright when I arrived last month.

“If we’re lucky enough to get the railings to stick down, another two weeks should do it,” said John Green, 73, who calculated that the project had taken more than two months and 2,600 man-hours.

Wright, 84, scowled at the rigging on a forward deck and marveled at the sheer volume of materials that went into the original 882-foot-long ship. At launching it was the largest ship on Earth. And yet, he said, “if the United States hadn’t made a movie out of it, 90% of the people wouldn’t have known about that boat.”

My next stop was a barstool near the oyster bar of the Five Fishermen, a fancy restaurant and grill in a two-story stone-and-wood building on Argyle Street. In its promotional materials, the restaurant leads with the building’s history as a school beginning in the early 19th century. But if you keep reading, you find that by 1912, part of the structure had become John Snow & Co. Funeral Home.

Though most Titanic victims’ bodies were taken from the Mackay-Bennett to the Mayflower Curling Rink (where ample ice was helpful in setting up a temporary morgue), historians say about 10 were delivered to Snow’s. If you ask, the staffers can show you an upstairs room, now filled with wine bottles, where coffins were hoisted. Staffers at the Five Fishermen also indulge talk about the place being haunted, but for me, the tangible history is enough.

Dinner was good—not at all like the most infamous meal of the “Titanic”movie shoot in August 1996. On the last night of scheduled shooting in Halifax-adjacent Dartmouth, caterers served director James Cameron and his crew a seafood chowder that sent him and dozens of others to the emergency room, many with hallucinations. Tests revealed the chowder was spiked with PCP.

No blame was ever publicly fixed for the poisoning, and some in Hollywood suggested that Cameron’s movie was becoming an over-budget, behind-schedule disaster in itself. Then the film came out in 1997, grossed more than $1 billion and doubled attendance at the Halifax Maritime Museum.

My second day in town – cemetery day – dawned appropriately gray, wet and chilly.

Blair Beed, a lifelong Haligonian (that’s what Halifax people call themselves) who has been guiding visitors for 39 years, ushered me into his car at 9 a.m. Then he let loose a torrent of Titanic facts.

We saw the former home of Halifax’s only homegrown Titanic victim, businessman George Wright. We saw churches where services were held, including St. Paul’s Church on Argyle Street, among the oldest Protestant churches in Canada. We did not see the Mackay-Bennett (it was scrapped decades ago) or the old curling rink (razed and replaced by another in a new location.) Then we headed for the graves.

At Mount Olivet Cemetery, we paid respects at 19 markers, some bearing names, some not. At Baron de Hirsch Cemetery, a private Jewish burial ground, I peered over the fence at 10 more grave markers, mostly unidentified. At Fairview Lawn next door, we found grave-digger John Rooke quietly at work in his rain slicker near the Titanic section, which we otherwise had to ourselves.

It sneaks up on you.

As Beed led me up and down the four rows of Titanic graves, I realized that the last row, which bends to follow the contour of a gentle hill, curves like the bow of a ship. Many visitors before me have noticed the same thing. Yet for all the experts on Titanic minutiae, not one seems able to say for sure whether this effect was by design or a coincidence caused by the lay of the cemetery land.

As for the 121 graves themselves, Beed told me, three get much of the attention. One is the marker for John Law Hume, 29-year-old first violinist in one of the ship’s two bands, and, sure enough, someone had left a shiny toy violin and a pair of red roses. Another much-visited marker is dedicated to an “unknown child,” one of more than 50 children who died. (After DNA testing, many experts now believe the unidentified remains to be those of Sidney Leslie Goodwin, the same 19-month-old English boy whose shoes are on display in the Maritime Museum. The boy’s parents and six siblings, traveling third class, all died on the ship.)

The other gravesite where many visitors linger—and teen-aged girls have been known to howl—is the marker for “J. Dawson.” Jack Dawson, of course, was the name of Leonardo DiCaprio’s fictional character in the film “Titanic.” The real J. Dawson was Joseph, a 23-year-old Irish boiler-room worker.

For the sake of those deeply attached to all things Titanic, I should mention that there’s still room at Fairview Lawn Cemetery. (A sign near the entrance offers plots for sale.)

For those not as deeply attached, I should add that I did spend more time among the living in Halifax. I stayed at the Waverley Inn, an unfussy hotel that has stood since 1876 and was charging just $107 a night. I had lunch at Henry House, a bustling pub in an 1834 stone house on Barrington Street. I had dinner at the Economy Shoe Shop Café & Bar on Argyle Street, an even livelier, sprawling, semi-Moroccan place that teemed with collegiate and post-collegiate types.

I eyed the landscape paintings at Zwicker’s Gallery on Doyle Street, dawdled at the Halifax Seaport Farmers Market (established in 1750 but now in a spiffy new building full of energy-saving gadgets) and nibbled charcuterie tidbits at Obladee, an upscale wine bar that opened in 2010. I read about local plans for late April 14 (a candlelight procession and concert) and early April 15 (tolling church bells and fireworks to recall the ship’s distress rockets), and gave silent thanks that I would miss the April run of a locally produced “Titanic” stage show that’s billed as “the ultimate dinner theater experience.”

I also found the hotel where I’ll stay on my next visit -- The Halliburton, a stylish trio of 19th-century townhouses now refashioned into a 29-room boutique inn with snazzy restaurant.

And then, on my last afternoon in town, against all expectation, the sun came out.

So of course I returned to Fairview Lawn. Sure enough, a dozen visitors arrived to browse the Titanic aisles in the space of 15 minutes, and taxi driver Jack Robar stopped by the curb to drop off a customer.

In 67 years as a Haligonian, Robar told me, he’d never been into the cemetery. But before this centennial year is over, he said, he will.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.