The Seattle of Jimi Hendrix summons the soul of the legendary musician

SEATTLE — This sprawling city overlooking Puget Sound has been home to some of the world’s most influential singers and songwriters, including Quincy Jones, Judy Collins and Kurt Cobain. But another musician, whom Rolling Stone magazine contends “exploded our idea of what rock music could be,” is known to elderly residents as Buster, his childhood nickname.

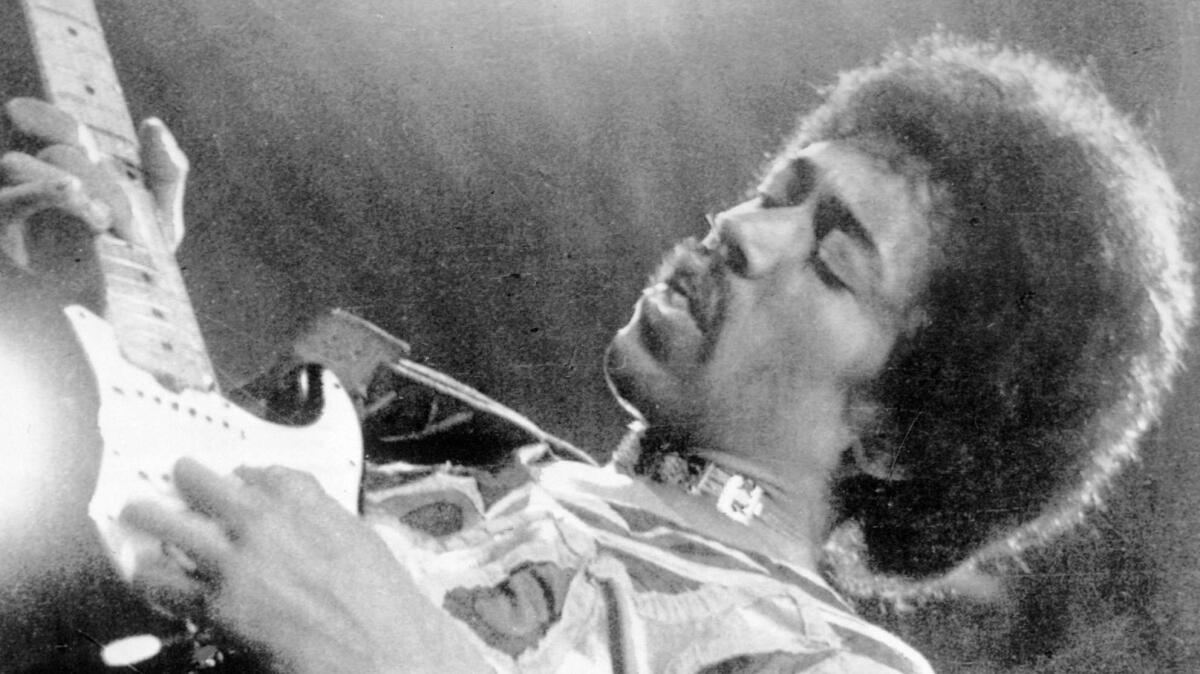

Jimi Hendrix would have been 75 years old on Nov. 27. His legacy as one of — if not the greatest — electric guitarist of all time is celebrated here in ways formal and fanciful, proper and peculiar, characterizations of the different life stages of this “West Coast Seattle Boy.”

The first of those stages began in 1942 when 17-year-old Lucille Jeter Hendrix delivered a baby boy at Harborview Hospital. Al, the child’s father, was stationed in the South Pacific during World War II and would not meet his son for nearly three years.

Seattle then had fewer than 400,000 residents. Pike Place Market, one of the city’s most popular attractions, had been operating 35 years. The opening of Sea-Tac International Airport was still five years away; the Space Needle 15 years after that.

Hendrix’s early life was a “never-ending shuffle” among apartments, boarding houses and low-rent hotels, according to Charles R. Cross, author of “Room Full of Mirrors: A Biography of Jimi Hendrix.” His parents divorced when he was 10. His father, a landscaper, along with assorted family members and friends, raised the boy.

At age 10, Hendrix started listening to Nat King Cole and other popular singers, playing along on a broom. His air-guitar career lasted four years; in 1956, he acquired a one-string acoustic guitar just before being hauled away as trash. A family friend paid $5 for it.

“Jimi turned the guitar into a science project,” Cross wrote. “He experimented with every fret, rattle, buzz, and sound-making property the guitar had.”

Another life-changing experience occurred the next year. At Sick’s Stadium, where Seattle’s Triple-A baseball team played, Hendrix witnessed a grand slam that had nothing to do with baseball: He saw Elvis Presley perform. Between the King’s gyrating hips and gold lamé jacket, young Jimi was mesmerized.

As Jimi’s interest in the guitar evolved into a passion, his grades began to plummet. In ninth grade, Jimi got an F in music, and his teacher recommended he pursue some other profession.

When Hendrix was 16, his father bought him his first electric guitar. Soon, the young man was performing regularly with local groups, mixing blues, jazz and rock. That growing notoriety was cut short in 1960 when he was arrested twice in one week for being in a stolen car. Facing a likely prison sentence, Hendrix joined the Army, and on May 29, boarded a train for California’s Ft. Ord.

Eight years later in February 1968, now an international rock star, Hendrix returned to his hometown for a sold-out show.

Microsoft fan

Seattle has no bigger Hendrix fan than Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen, who created the Museum of Pop Culture, or MoPOP, a Frank Gehry-designed museum originally intended to celebrate Hendrix’s music and the guitar.

Artifacts include remnants of the guitar he set afire at the 1967 Monterey Pop Festival and the white Fender Stratocaster Hendrix played at Woodstock in 1969. The current exhibit chronicles the last four years of his life, which ended Sept. 18, 1970, in London.

On a recent Friday afternoon, visitors thumbed through Hendrix’s passport and inspected a Trans World Airline bag he used while on tour.

“‘Wild Blue Angel’ is the seventh Hendrix exhibition that we’ve created since we opened in 2000,” said Jacob McMurray, senior curator.

“I like the idea of not always re-creating a survey of Hendrix’s life, career and legacy, but to focus on specific aspects of Hendrix’s life or to use Hendrix as a lens to talk about relevant cultural topics.”

There are more than 100 pages of handwritten lyrics, most of which are on airline and hotel stationery.

“That got me thinking about just what it must be like for Jimi Hendrix at the height of his popularity, essentially not having a home and just feeling the need to create wherever he was, on a plane, in a hotel after a gig, etc.,” McMurray said.

“That framework allowed me to think about every object that we have on display as an opportunity to explore Hendrix’s itinerant, creative lifestyle, from his perspective and from the perspective of the fans and press that were covering him at the time.”

Those seeking souvenirs need look no farther that the museum’s gift shop, which offers the customary books, photos and T-shirts, as well as guitar picks and four types of “instant collectible” Hendrix-engraved pennies.

A park place

Twelve miles south of MoPOP, Janie L. Hendrix, the musician’s stepsister, is overseeing the completion of 2½-acre park honoring her brother. Visitors today see a glimpse of what is yet to come: a butterfly garden, a bright orange sculpture casting a heart-shaped shadow and Hendrix’s inimitable signature at the entrance, which is shaped like the head of a Fender guitar.

Thanks to a donation from Sony earlier this year, she expects completion in 2018.

The park is adjacent to the Northwest African America Museum, whose artifacts include a wide-brimmed black hat Hendrix wore at a concert in 1968 at the Shrine Auditorium in Los Angeles.

In stark contrast, across town is another Hendrix memorial that’s as peculiar and quirky as the park is fanciful and inspiring: It’s a rock in the city’s Woodland Park Zoo.

The rock, large enough for children to climb onto and gaze at nearby ostriches, was dedicated with a brass plaque in 1983, after a two-year effort by Janet Wainwright, then promotion director at a local rock-music radio station.

“Almost without exception, I encountered resistance, mainly due to the fact that people ignored his obvious contributions to the music of our nation and focused on the drama of his death and accusations of drug use,” said Wainwright, who now runs a marketing firm.

“I think Jimi has been recognized as a great guitarist, if not the best, for a very long time. Even kids who don’t routinely listen to him recognize his stature. He is iconic.”

During the past 25 years, zoo spokesperson Gigi Allianic has hosted film crews from the Netherlands, Germany, Japan and China all “covering” the rock. The rock has a heating element that, one news story said, is intended to “honor Hendrix’s ‘hot’ rock ‘n’ roll and psychedelic-blues music style.”

Renton tributes

Few Hendrix fans trek to Seattle without paying homage at Greenwood Memorial Park cemetery in nearby Renton, where Hendrix, his father and other family members are enshrined in a domed memorial.

Images of the guitarist are etched in marble, on which women leave lipstick marks.

On a Saturday in early October, Rhonda Cruz, who turned 60 that day, was taking photos with her phone, the cover for which has an image of the guitarist.

“When I was a young girl, I thought he was so handsome and I loved his music [and] I’ve loved him ever since,” said Cruz, visiting Seattle from Colorado for the first time to pay her respects.

“To me, his music is his legacy and just how passionate he was about his music and creating it. He inspired love and individuality, and that same message, along with his music, is undying to this day.”

Thousands of fans from around the world visit the site, according his stepsister, who serves as president and chief executive of the family company managing the guitarist’s name, image and music.

“My dad had the memorial built as a way of honoring Jimi and also to properly house Jimi and other family buried there,” she said.

“Knowing how loved Jimi was, he wanted to create a place for the fans to come, sit and stay dry during rainy weather and snow. It was a vision he had for keeping Jimi’s memory alive, and it has proved to be a welcome idea and a gift to the public.”

IF YOU GO

Where to stay

The Edgewater, 2411 Alaskan Way, Seattle; (800) 624-0670. Channel your inner rock star by booking the Beatles Suite, where the Fab Four stayed on their first U.S. tour in 1964. The 750-square-foot room includes photos, Union Jack throw pillows and, of course, a stereo system with Beatles songs. Weekend rate is about $700 a night, plus taxes and fees.

Hyatt House Seattle/Downtown, 201 Fifth Ave. N., Seattle; (206) 727-1234 or (800) 323-7249. The hotel is a short walk from MoPOP, the museum of popular culture with ongoing Hendrix exhibits; weekend rates start at $169 a night, plus taxes and fees.

Quality Inn, 1850 S.E. Maple Valley Highway, Renton, Wash.; (425) 226-7600. Just off Interstate 405 south of Seattle and a five-minute drive to the Greenwood Memorial Park where Hendrix is buried. Weekend rates start at about $75 a night, plus taxes and fees.

Where to eat

Ray’s Boathouse, 6049 Seaview Ave. N.W., Seattle; (206) 789-3770. Among Seattle’s top-rated seafood restaurants. Be sure to book a reservation to savor the sunset over Shilshole Bay, as well as the salmon, scallops, or halibut. Entrees run $30-$60; less expensive in the less formal Ray’s Café upstairs.

Big Chickie, 5520 Rainier Ave. S., Seattle; (206) 946-1519. In a remodeled gas station in one of the neighborhoods where Hendrix lived, this informal restaurant offers Peruvian-style charcoal rotisserie chicken with a dozen side dishes. Don’t overlook the gluten-free, lime-glazed sweet potatoes. Entrees $9 to $19.

To learn more

Experience Hendrix, official site of the singer/guitarist offers music, videos, merchandise and all things Jimi.

Visit Seattle, 701 Pike St., Suite 800, Seattle; (206) 461-5800.

ALSO

The secret’s out and there’s no schussing it: Seattle’s a great ski town

In Portland, ignore the mizzle (mist and drizzle) and enjoy dining outside, Pacific Northwest style

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.