Postcards From the West: California’s redwoods: In the land of the giants

California’s majestic old-growth coastal redwoods -- the tallest trees on Earth -- can leave you humbled, awed and waxing poetic.

Reporting from LEGGETT, Calif. — It was the first full day of my redwood country road trip, about 180 miles north of San Francisco. John Stephenson was showing me his drive-through tree, a 315-foot beauty that’s the pride of Leggett.

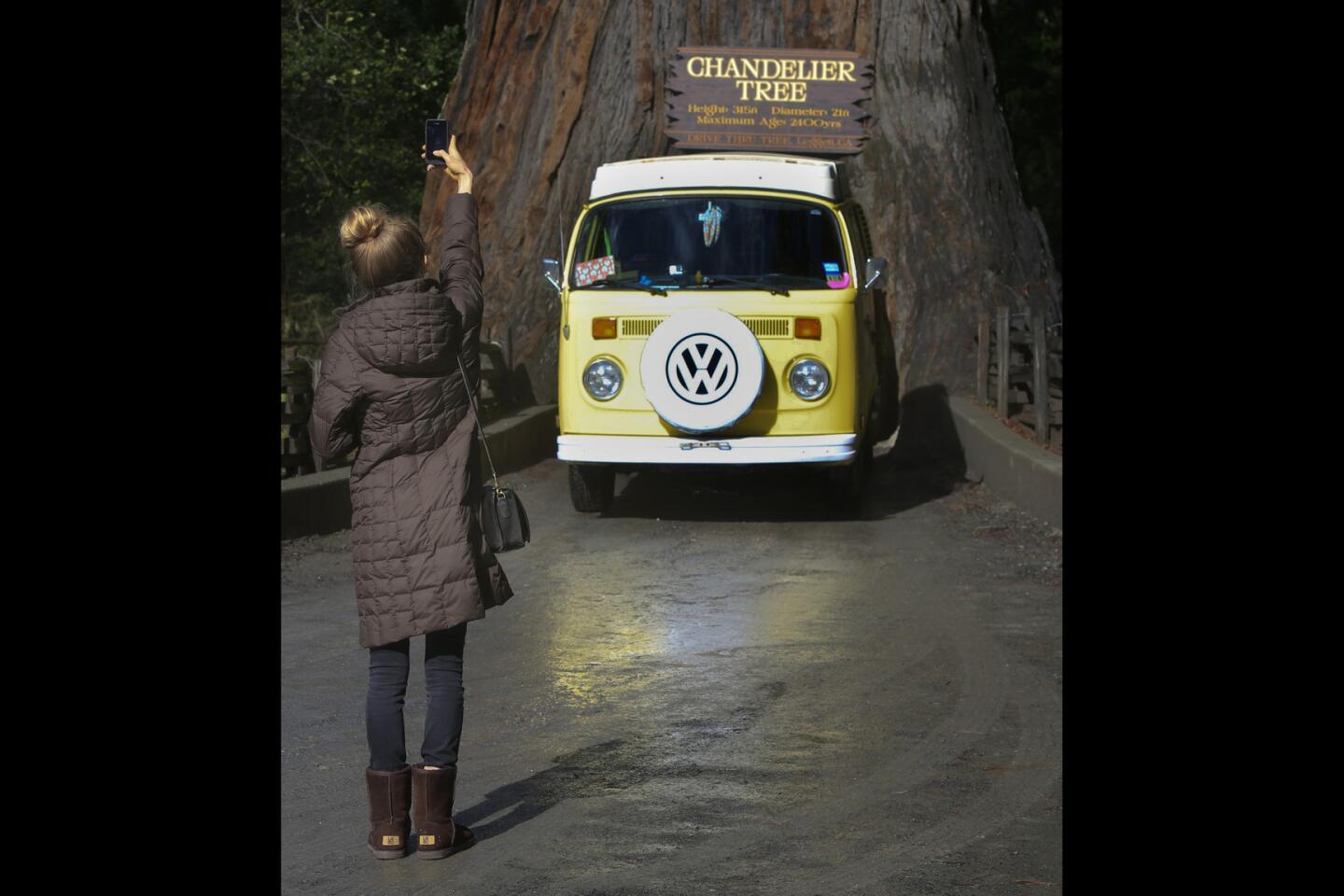

A storm had just roared through. Raindrops trickled from the forest canopy, and tendrils of steam drifted up from the rough bark of the pass-through trunk, where redwoods store much of their moisture. I thought Stephenson was going to remind me that the tree was called the Chandelier Tree, or that it was 2,400 years old.

“My brother and I were conceived here,” he said instead. The family story, he continued, is that “my mom and dad would park in there and make out.”

The next day, I was at the Shrine Tree, another drive-through attraction about 40 miles north of Leggett. The manager, J.D. Allmon, was standing by a tarp-covered lump.

“Hey,” he said. “You want to see something?”

Then he pulled back the tarp, revealing a 7-foot-long section of redwood trunk, stripped, hollowed and planed to make a long box with removable lid. It was a coffin, nearly done, commissioned by a very sick friend.

“I’ve been working on this thing for two years, and he ain’t keeled over yet,” Allmon said. “He paid for the materials. I didn’t charge him. I wanted to do it.”

California’s old-growth coastal redwoods are the tallest trees on Earth, and the old-timers thrive in the foggy, rainy territory between Mendocino and the Oregon line. For many locals, these trees don’t just dominate the landscape; they connect with matters of life and death — even now, years past the timber industry’s glory days.

If you’re visiting, as Times photographer Mark Boster and I were in early spring, you can’t count on hearing true tree confessions from everybody. But if you take a minute to step away from your car, you’ll feel belittled in the best possible way.

We started by driving 550 miles up U.S. 101, from Los Angeles to Leggett, where Stephenson’s Chandelier Drive-Thru Tree looms above Underwood Park. We spent two nights in the stately old Benbow Inn in Garberville, which opened in the 1920s just as the new highway was beginning to make big-tree tourism accessible.

Then we continued into Humboldt and Del Norte counties, beginning with the 32-mile Avenue of the Giants between Garberville and Fortuna, where the old growth of Humboldt Redwoods State Park alternates with roadside kitsch, and coonskin caps can still be had for $8.99. We pulled out our long lenses to snap elk near the old red schoolhouse in Trinidad and headed into the park belt — a long, noncontiguous series of public lands that begin above Orick and stretch more than 70 miles north to Crescent City, including Prairie Creek Redwoods, Del Norte Coast Redwoods and Jedediah Smith Redwoods state parks, which together make up about half of Redwood National and State Parks.

Hiking in Prairie Creek Redwoods State Park, we wondered whether the tallest tree in the world was hiding in plain sight. (It’s somewhere in the park, but rangers and serious tree people don’t disclose these things.) And we may have gasped a few times.

You step into the forest and wade through ferns and ground-hugging oxalis, dodge poison oak, glance at moss-covered maples and Douglas firs. You run your hand along the soft, damp redwood bark — redwoods are related to sequoias but grow taller — you feel the soft floor of fallen leaves and needles underfoot. You consider the tonnage, the fires, the floods, the centuries towering above you.

We roamed there with Christine Driscoll and Ann Wallace of Redwood Photo Tours, and I kept thinking about “The Wild Trees,” Richard Preston’s riveting book about tree researcher Stephen C. Sillett and the small band of compulsive climbers, mappers and catalogers who have revolutionized redwood research since the late 1980s.

Preston calls these trees “the blue whales of the plant world.”

They could have been the dodo of the plant world. By the time the Save-the-Redwoods League rose up in 1918 to protect them, the timber industry had logged about 95% of the region’s old-growth forest in less than a century. By the 1940s, when Woody Guthrie gave the redwood forests a starring role in his lyrics to “This Land Is Your Land” — the trees were even more besieged, yet there was still no national park for them.

Now we have Redwood National and State Parks, created in 1968, which get about 400,000 visitors a year.

Unfortunately, a few of them are poachers bearing chain saws. What the poachers want are redwood burls, irregular growths that protect a tree’s health, weigh hundreds of pounds and fetch hefty prices. To get at them, poachers sneak in overnight and sometimes fell entire trees.

Jeff Denny, supervisory park ranger for Redwood National and State Parks, reported 18 poaching incidents last year and 43 since January 2011. On March 1, rangers closed the Newton B. Drury Scenic Parkway to traffic after dark.

Sometimes, Denny said, “folks who have grown up around these [trees] see them differently than folks who didn’t.” Indeed, you hear all sorts of stories about what people do when redwoods are at stake.

Local innkeeper Janet Wortman, whose Yurok ancestors have lived along the Klamath River “since the beginning of time,” told me over dinner about how, long before white people arrived, her tribe made houses with redwood planks. Before felling a tree, she said, the men would fast for days to show respect.

Bill Hiney, a timber business veteran from Eureka, Calif., who was sitting at the same table, weighed in with a story about a father and three sons who risked their lives by taking a boat out on the Klamath River during the flood of ‘64, which leveled downtown Klamath and most of Requa, washed out the 101 bridge and flung countless trees into the sea.

Once the guys were on the river, Hiney told us, they spotted an old-growth specimen amid the floating lumber, and one of them jumped onto the tree to put a lumberjack’s “choke” on it. Then they guided the long log from the roaring river to a patch of riverbank. When the log went to the mill, they got a big payday.

“In a flood!” Hiney said. “In a 14-foot aluminum boat!”

Implausible? Unverified? Told by a man who has spent 40 years trading tales with lumberjacks? Check, check, check.

After that drama, I shouldn’t admit that my big tree moment came in a calm, still patch of forest, but it did. At Founders Grove in Humboldt Redwoods State Park, you can stroll from the parking lot to the 346-foot Founders Tree, and from there it’s about half a mile to the Dyerville Giant, a massive redwood that fell in March 1991 after a month of hard rain.

The tree was perhaps 2,000 years old when it came down, and the grove has a graveyard hush. You can’t help but imagine the morning when that giant collapsed — the groaning wood, the churning earth, the whoosh, the million-pound impact. Some people, the sign says, mistook the sound for a train wreck.

To pace the tree’s length, top to bottom, is a journey of about 360 feet. And when you reach the crater where its shallow roots once gripped the earth, you get a surprise: Like many fallen redwoods, the Dyerville Giant has started sending up a new trunk from the side of its old base.

The new trunk is more than 10 feet tall now. So this tree’s graveyard is also its nursery. And who knows? With 2,000 years and a bit of luck, the new giant might surpass the old.

_______

A brief history of California’s redwoods

25 million years ago

As the Miocene Epoch advances, redwoods grow across the Northern Hemisphere, leaving fossils to be found from California to Pennsylvania. Also Greenland, France and China.

1828

Trapper and explorer Jedediah Smith leads a team through land that will become Redwood National and State Parks. He’s looking for a new route between the Pacific and the Rocky Mountains. He’s apparently the first white man to explore the northern coast overland, although many native tribes have lived among the redwoods for years.

1853

A timber boom occurs in the wake of the California Gold Rush. By year-end, nine sawmills are operating in Eureka.

1879

First effort to establish a Redwood National Park fails.

1900

The coastal redwoods’ territory has shrunk to a strip from Monterey County, Calif., to the Chetco River in Oregon. Two other related species survive elsewhere: In California’s Sierra Nevada, the giant sequoia, which is bulkier and shorter than the coastal redwood, and central China’s dawn redwood, which is shorter and thinner than the other two.

1918

Save-the-Redwoods League is founded. Over the next few years, private donations fund acquisition of thousands of acres in Northern California.

1920s

The new Redwood Highway boosts commerce, tourism and growth (including the opening of the motorist-friendly Benbow Inn south of Garberville). The Save-the-Redwoods lands become three state parks: Prairie Creek Redwoods, Del Norte Coast Redwoods and Jedediah Smith Redwoods.

1945

As World War II ends and a home-building boom begins, demand for redwood lumber soars.

1960

Road crews reroute U.S. 101 bypass, allowing a 32-mile stretch of the old highway (north of Garberville and south of Fortuna) to become a scenic highway known as Avenue of the Giants.

1964

Klamath River floods, causing extensive damage.

1968

After decades of resistance by the timber industry and years of campaigning by the National Geographic Society and others, Congress creates Redwood National Park. Most of its 58,000 acres, however, are within the three state parks that were set aside decades before. Much of the Redwood Creek watershed, where many of the biggest trees grow, remains unprotected.

1978

Congress expands the national park, adding more of the Redwood Creek watershed.

1994

The National Park Service and California Parks system agree to jointly manage their parks.

2005

Congress again expands Redwood National Park, adding the Mill Creek watershed. The park now contains 131,983 acres, of which 71,715 acres are strictly federal and 60,268 acres are both state and federal parkland.

2006

Researchers discover a 379-foot redwood — apparently the world’s tallest tree — along with two others more than 370 feet, in a secret spot along Redwood Creek.

2013

Rangers count 18 wood-poaching incidents, up from 17 in 2012 and eight in 2011.

Sources:

“Redwood: The Story Behind the Scenery,” by Richard A. Rasp;

California State Parks, https://www.parks.ca.gov and

National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/redw/faqs.htm, https://www.nps.gov/redw/historyculture/area-history.htm

_______

John Stephenson’s family tree comes with a drive-through

John Stephenson’s family tree is nothing like yours. It’s a coastal redwood in Leggett, Calif., and you can drive a Chevy Suburban through it. It’s been owned by Stephenson’s family for four generations.

On road maps, it’s known as the Chandelier Tree. It’s the centerpiece of 305-acre Underwood Park ($5 per car). The idea of such a place enchants some travelers and befuddles others, because many people reckon that a drive-through tree must be public property.

But no, northernmost California’s two other drive-through redwoods are also family businesses on private property. The Shrine Drive Thru Tree in Myers Flat, $6 per car, is in Humboldt County. The Tour-Thru Tree, $5 per car, stands in Klamath in Del Norte County.

Stephenson, 51 and treelike himself at 6 feet, 4 inches, tells tourists to see all three, “because they’re not making any more.”

Having driven through all three on this trip, I can report that the Chandelier Tree is the sturdiest, most photogenic and the only one that’s staffed year-round. But that doesn’t mean this is an easy business.

“It’s a living organism,” says Stephenson. “It could fall over any minute, and we all go home.”

Stephenson’s great-grandfather bought the property in 1921 and named it Underwood Park. He opened it as a roadside attraction in 1922. In the mid-1930s, the family cut a pass-through hole in the tree and called it the Chandelier Tree because of its shape.

By the 1960s, the park had 20 cabins, a bar, soda fountain and recreation hall. One of Stephenson’s first memories, he says, is standing in the back seat of his great-grandmother’s Dodge Dart, about age 4, his arms resting on the top of the front seat, as she accelerated toward the gap.

“My great-grandmother would roll through here at about 30 mph. Then she’d laugh and go around and do it again,” he recalls. “She drove through the tree every day.”

As air travel gained in popularity and the timber industry dwindled, business slowed at Underwood Park. Stephenson, who spent most of his career building a transportation company, turned down three chances to take over.

But when his grandfather died in 1994, the responsibility fell to him and his brother, Tom, 53.

My great-grandmother would roll through here at about 30 mph. Then she’d laugh and go around and do it again.

— John Stephenson, recalling his drives through the Chandelier Tree with his great-grandmother

Stephenson sold his company in 2006 and now commutes to Leggett from his home more than two hours south near Santa Rosa. He chooses gift-shop products, keeps 4,937 feet of road clear and smooth and pulls out a wire grinder occasionally to remove graffiti from the tree. And because Stephenson can’t stand the sight of vandalism in Underwood Park’s restrooms, he buys mirrors by the dozen at $26 each.

There’s no special treatment for the tree, just a visit from an arborist every five to 10 years, to trim dead matter and keep the opening passable.

The park loses money for nine months of the year, Stephenson said, but usually makes enough in summer (when up to 500 cars a day show up) to cover those losses and pay for new projects. Right now, Stephenson is fixing up the old rec hall as a wedding venue. And he recently bought the park’s first new tractor in 50 years.

He’s guessing that none of his sons or stepsons will want to take over, so the long-term fate of the tree is uncertain.

Meanwhile, the cars keep coming, even on a rainy Monday in March. Couples, families, wide-eyed kids. A yellow VW bus from Texas approaches, then retreats — camper top too high. The occupants of a silver Lexus, having driven from Washington state, pop through the sunroof to pose for pictures.

Stephenson remembers the old man who scraped up a new Ford pickup driving through and didn’t mind a bit because the adventure had made his two grandsons happy. Stephenson also remembers the day in the mid-1970s when three or four young guys on a cross-country road trip realized that their old van was a little too tall for the tree. So they climbed on top and stomped on the roof until it fit.

But the best moments with his family’s tree, Stephenson says, happen when no one is around. After a rain. When the dogwoods bloom. When a full moon throws shadows on the forest floor.

“Most people in their lives are not going to get to see that,” says Stephenson. “And I get to.”

_______

Mouth of the river, 0:12. Building from 1914, 0:26. Redwood bits, 0:36. Looking for whales, 0:48. Pacific panorama, 1:09.

Splendid views and other favorites in California’s redwood country

For vertical views, you can’t beat redwoods. But the best horizontal vista I found in redwood country was the Klamath River emptying into the Pacific, seen from the Klamath River Overlook at the end of narrow, ragged Requa Road, about 40 miles south of the Oregon line.

From that overlook, about 650 feet above sea level, you can often spot gray whales migrating and see the river water mixing with the seawater. (In fact, as the tides rise and fall, the river appears to change direction.) You can also hike down a short, steep trail to an even more dramatic set of views. The light is best at sunset, and there’s a picnic table.

My favorite lodging in redwood country was along the Klamath River too. The Historic Requa Inn, a semi-rustic landmark, is about half a mile from the end of Requa Road. The white, two-story inn is one of the few commercial buildings left in the town of Requa, much of which was swept away by the flood of 1964.

The inn dates to 1914, when the only way to cross the river was by ferry. Besides offering 13 rooms at $119 to $199 a night (breakfast included, no TV, no phones, iffy Wi-Fi), the inn serves four-course dinners ($45 per person, reservations required) six nights a week, beginning promptly at 7 p.m.

If you’re lucky, you’ll get a chance to hear some local history from innkeepers Janet and Marty Wortman, who bought the place in 2010, or their son, Thomas Wortman, who is the chef. Janet, Thomas and Thomas’ sister, Geneva, are members of the Yurok tribe, whose long, narrow reservation follows the Klamath River for 43 miles, extending one mile from each bank.

If I’d had more time, I’d have explored the Klamath estuary on a two- to three-hour electric canoe tour with local naturalist William Ihne ([707] 954-8277), a former teacher who usually starts his expeditions at the nearby fisherman-friendly Gold River Lodge. One morning recently, Ihne spotted 30 osprey catching eels, a green heron and three golden eagles.

I settled for a foray along the rugged roads just south of the river. If you exit Highway 101 at Klamath Beach Road and head west, you enter Redwood National Park. Follow Coastal Drive and Alder Camp Road to make a nine-mile loop. The route includes several stopping points with broad views of the rocky coastline. Highlights include views from Flint Ridge and High Bluff Overlook and a glimpse of a World War II radar station that was disguised to look like a dairy farmhouse and barn.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.