The gorgeous and the grim in Dublin, Ireland — and the green hills beyond

This video zips through Dublin, including one of its most gorgeous addresses (the library that holds the Book of Kells) and one of its grimmest (the Kilmainham Gaol). We wind up on a hilltop in County Meath where St. Patrick is said to have lit an E

Maybe you can’t get to Ireland for Saturday’s St. Patrick’s Day celebrations. But let me take you now to Dublin’s most gorgeous library, its grimmest address and a country ruin where, 16 centuries ago, St. Patrick himself might have done something startling.

All three spots won me over last spring, when my wife, Mary Fran, my daughter, Grace (then 12), and I had a chance to visit Ireland together for the first time.

Not that we had a lot of time. Most of our waking hours were consumed by the World Irish Dancing Championships (another story entirely; picture a six-day production of “Riverdance”). Even though we were digesting plenty of Irish culture in jig, reel and hornpipe form, we never did get to a lot of top tourist attractions, such as the Guinness Storehouse or the Jameson Distillery. Or any art museums or writers’ houses.

But we did cross the River Liffey on Ha’Penny Bridge; feed oats to swans on St. Stephen’s Green; and tip a busker on Grafton Street. And most memorably, we got to the Long Room of Trinity College’s old library; Kilmainham Gaol; and the Hill of Slane in County Meath.

The Long Room

The Book of Kells, carefully guarded in the Old Library of Trinity College downtown, is one of Dublin’s star attractions. To get in, we joined a long, international line of tourists paying about $15 per adult (kids younger than 12 are admitted free) to inspect a few well-guarded pages of the treasured book.

And I did look closely at those pages in the library exhibition space. Hand-written by monks in about 800, the book is considered remarkable for its immaculate calligraphy and fine illustrations — the emojis of the 9th century, I told Grace. So yes, I remember it.

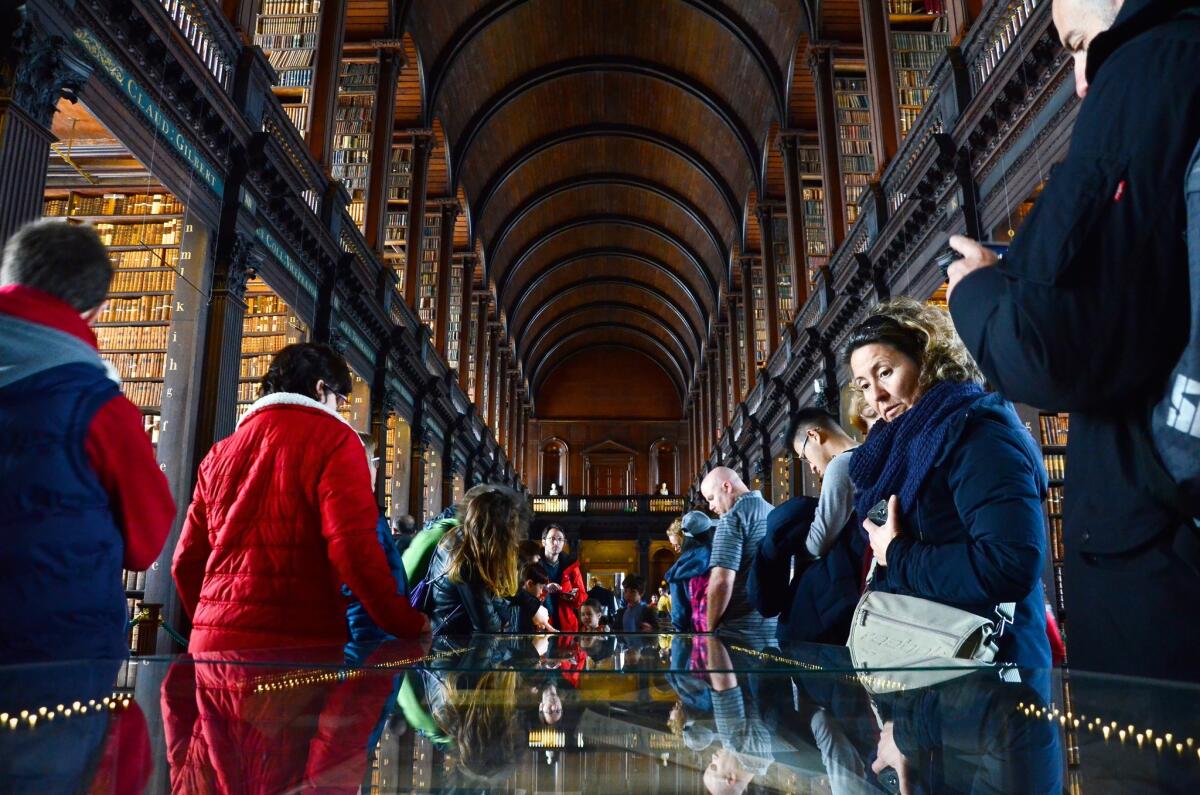

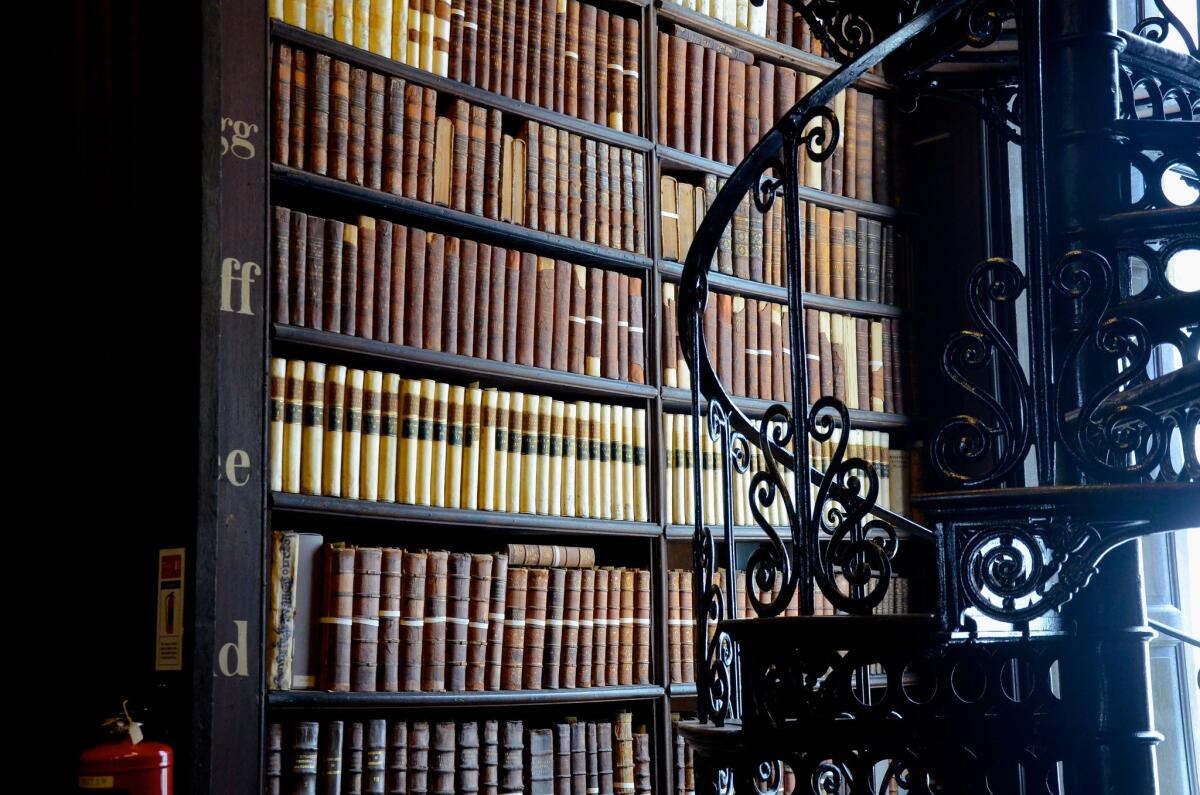

But what I remember better is the upstairs room that comes after the precious pages. The library’s Long Room, built in the 18th century and expanded in the 19th, stretches for about 200 feet, with a high, barrel-vaulted ceiling above walls that fairly groan with the weight of ancient books and granite busts of learned persons. (All men, so far.)

About 200,000 very old volumes line these walls, joined by a harp that is said to be the oldest in Ireland, and as you file through, you’ll likely feel your jaw slackening.

I’ve seen some fairly amazing rooms full of books over the years, including the New York Public Library; the Palafoxiana Library in Puebla, Mexico; and the Livraria Lello in Porto, Portugal, but the Long Room mingles books, history, beauty and wonder like no place else I’ve seen.

It’s Hogwarts with an Irish brogue. Having gobbled up all the “Harry Potter” books and movies, Grace was smitten too. We lingered long as the crowds would allow, then passed another long spell in the gift shop.

The most popular prison this side of Alcatraz

Kilmainham Gaol, as it happens, is another building born in the 18th century -- opened in 1796 on Gallows Hill, closed in 1924, revived as a historic site in the 1960s.

If these grimy, dank buildings had only ever harbored justly convicted thieves, murderers and other criminals, the site, about two miles west of the city center, would make a fine scared-straight experience for all the world’s impressionable teenagers.

Having paid our $10 per adult, we stepped through the chilly rooms, which until the 1880s often held men, women and children together. Leaned close to check out the scratchings on the walls. Leaned back to see slivers of sky above. Paused at the imposing entrance, where hangings took place until about 100 years ago.

But the other part of the Kilmainham story is its role in Irish independence. And the leaders of these tours make the most of it.

As you step from one dispiriting room to another, your guide gives you the big picture, offering anecdotes from a handful of individual prisoners. As the tour advances, the political aspect deepens and the stories edge into more emotional territory.

Our guide, Wayne Brereton, said he had been on the job only a year, but he made it a powerful tour.

In 1798, 1803, 1848 and 1867, he told us, British authorities punished rebels here.

And it was here, after the 1916 Easter Rising rebellion, that British firing squads executed 14 rebel leaders – a move that mobilized the Irish public like nothing before. By 1922, Ireland – well, 26 of the island’s 32 counties – had won independence.

By the time your guide gets to 1916, you’ll be standing as we were in the walled gravel yard where the firing squad executed those 14 rebel leaders. If you don’t feel wounded yourself — and emboldened by the winning of independence — you haven’t been paying attention. (I’m not sure how this plays in the mind of an English tourist.)

Anyway, it’s a potent tour — the setting, the story, the delivery — and you’ll have a museum full of artifacts and old letters to examine afterward. By the time we stepped off the Kilmainham property, we were absolutely ready for the pub across the street, the Patriots Inn.

Meanwhile, on a green hill in County Meath

One night we were invited to dinner at the home of friends in County Louth, about 30 miles north of Dublin. On the way, we first hoped for to a visit to Newgrange, a Stone Age ruin older than Stonehenge or the pyramids at Giza. But an hour wouldn’t be enough for that.

So we roared up the highway, alert to possibilities. And as we crossed the River Boyne in County Meath, we spotted one.

Off the main road. Through a little town. Up a hill. There atop the very green Hill of Slane stood a stately set of ruins, surrounded by several dozen cows.

We parked. Fled the car. Snuck up on the cows. Occupied the ruins, roamed the graveyard, posed for album-cover photos and raced across the grass, down the hill to a great dinner with our friends.

What was this place? On this hill in 433, a sign said, St. Patrick himself is said to have lighted an Easter Fire in defiance of a Druid king. Historians are still arguing over what really happened, of course, but the BBC says people light a hilltop fire every year to keep the story alive.

The historians do seem to agree that the ruins, a church and friary, were built by the 16th century, abandoned in the 18th.

So basically, with no planning whatsoever, we found and claimed a perfect hour on a perfect pastoral hilltop with ancient ties to Ireland’s favorite saint. What, I wondered, are the odds?

But since then, I’ve thought more about all the hills, grass, history and myth in Ireland. I’m guessing that no matter which way we drive out of Dublin, we’ll be able to find another perfect hilltop next time. As will you.

Follow Reynolds on Twitter: @MrCSReynolds

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.