When you explore Jewel Cave and Wind Cave in South Dakota, revelations may be around the next corner

Since the dawn of time, humans have been bound to the cave. It's been our home, our tomb, our place of revelation.

The prophet Muhammad met the angel Gabriel in a cave; Zeus nursed in a cave; and Chaac, the Maya rain god, dispatched clouds from his subterranean lair.

The National Park Service has long recognized this primordial connection and oversees more than 4,700 caves, many open for exploration. Four of the seven longest caves on Earth — Mammoth Cave in Kentucky, Jewel Cave and Wind Cave in South Dakota, and Lechuguilla Cave in New Mexico — are managed by the park service. Each of the caves stretches more than 135 miles; Mammoth exceeds 400 miles.

About the series:

The 410 units of the National Park Service are as varied as the United States itself and an incredible legacy for Americans. The Los Angeles Times Travel section continues a yearlong look at some of those units, why they matter and how the park service is working to tell this country’s story. More in the series »

Caves, dark and forbidding, are places of great mystery. Hundreds of thousands honeycomb our world. Tennessee alone has 7,000. They shelter new species, massive crystal chambers and underground rivers and lakes.

Caves also play a critical role in our natural world as aquifers while providing clues to the climate millions of years ago through fossils, sediment and water levels.

"There are karst caves, lava caves and sea caves, and each one forms differently," said Dale Pate, cave and karst program coordinator for the National Park Service. "Visitors can take guided tours of caves or explore on their own. Some caves are open only for research. If we had people go in, they would be lost forever."

Most caves are formed in karst landscapes created by the dissolution of limestone, gypsum and dolomite by rainwater and carbon dioxide. As the rock dissolves, cracks form and caves appear.

George Veni, director of the National Cave and Karst Research Institute, a nonprofit dedicated to conserving these geological resources, describes caves as the veins, arteries and capillaries of the planet, moving critical water beneath the surface. When they dry up, they become time capsules.

"I have found human footprints in caves thousands of years old," said Veni, one of America's leading cave experts. "In Mammoth Cave there are 4,000-year-old baskets. In Guatemala and Belize I found Maya murals on cave walls."

Yet caves are harsh, almost otherworldly places. They're cold, there's little food and they are darker than space. Bats hang at the entrances, but the farther in you go, the scarcer life becomes. Yet it's there — fish with no eyes, microbes that eat rock — so perfectly evolved that it cannot survive on the surface.

But it's all very fragile.

Every year, the National Park Service removes hundreds of pounds of "lint," a euphemism for human hair, skin and crumbs people leave in caves. A tarp under a stairwell at Jewel Cave National Monument caught 100 pounds of hair in one year. Any of it could contaminate the cave ecosystem.

Aside from science, it's the lure of the unknown that draws most people to caves. They are the final frontier, lying literally under our noses. Jewel Cave officially extends 180 miles, but experts think it may run 5,000 more.

"I am one of many, many cavers who have been to places where there have been fewer people than have walked on the moon," Veni told me. "I have tremendous respect for Sir Edmund Hillary and Neil Armstrong, but with a cave you don't know what the goal is. I can see a mountain peak. I can see the moon. When I go into a cave, I don't know what I'll find."

With a cave you don't know what the goal is. I can see a mountain peak. I can see the moon. When I go into a cave, I don't know what I'll find.

— George Veni, director of the National Cave and Karst Research Institute

Daniel Austin, a physical science technician at Jewel Cave, leads mapping expeditions into its winding, uncharted regions.

He recently followed an eight-mile passage and discovered a clear underground lake 20 feet deep.

"I keep going because I always want to know what the heck is around that next corner," he said.

That ancient quest for revelation, be it scientific, personal or even divine, fuels many a spelunker.

After leaving the Air Force, Veni considered becoming a physician. But one night he had recurring visions of an underground river he had discovered in a West Texas cave.

"It was a singular moment that changed my whole life," he said.

Veni dropped plans for medical school, became a geologist and spent the next 40 years exploring caves throughout the world.

"Every cave is a revelation," he said.

Pate of the park service put it another way.

"One of the things I discovered in a cave," he said, "was myself."

Squeeze into Jewel Cave and you can feel Mother Earth breathe

As a committed claustrophobe, I am filled with dread at the sight of that little box outside the doors here.

Unless I could squeeze my 180-pound frame through that 81/2-by-24-inch block, I couldn't do the Wild Caving Tour, one of the most strenuous in the national park system.

I got stuck on my first attempt. Then I removed my sweatshirt, belt and shoes and pushed through. My son Nicholas, 19, made it easily, as did a trio of students from nearby Black Hills State University also on our tour.

We went to a changing room and donned knee and elbow pads while park ranger Kenneth Steinken passed out helmets with headlamps.

"Everyone experiences anxiety and nervousness in a cave; these are God-given survival responses," he told us. "You are hundreds of feet below tons of rock in small, tight spaces. Your brain is telling you this is not a usual thing, and it's not."

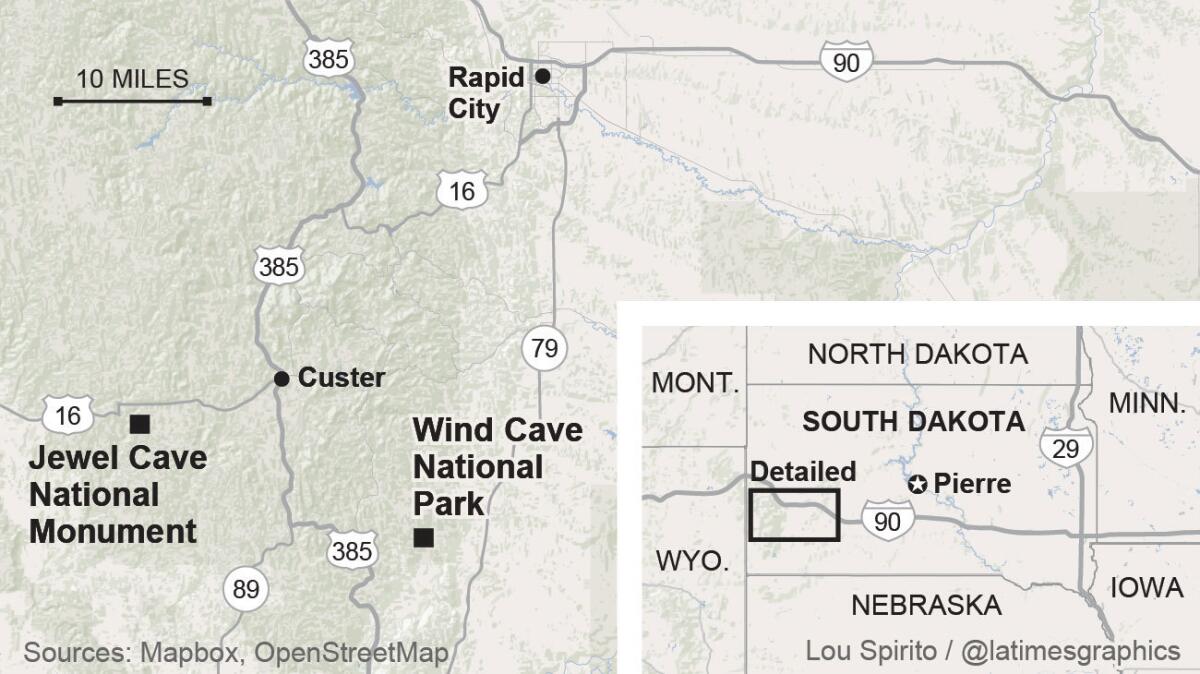

Jewel Cave, the third-longest on Earth, lies beneath the Black Hills near Custer, S.D. So far, 180 miles of cave have been found, but explorers make new discoveries all the time, including two underground lakes last year. Experts think Jewel could extend as far as 5,000 miles.

Our November tour was a tad more modest, perhaps half a mile. Yet it would take nearly four hours of crawling, climbing and fretting about being entombed for eternity beneath a billion tons of rock to finish it.

We took an elevator down to the main cave chamber where the popular Scenic Tour begins. That tour went right, using walkways and stairs to stroll through roomy caverns with illuminated crystals. We went left, plunging into darkness.

Our headlamps swiftly revealed shadowy ceilings studded with calcite crystals. Water dripped from the rock. It was a constant 49 degrees, fine if you kept moving, deadly if you were lost. The cave was slick with black manganese.

We traversed a deep trench by propping our legs against one wall and our backs against the other, then slowly moving across. We crawled through narrow passageways with tight corners.

"Don't fight the rock. You'll never win," Steinken said. "Think of yourself as a puzzle piece that fits around the rock."

He was right. I blew air out of my lungs to flatten myself as I slid under rock ceilings less than a foot high.

We emerged inside a cramped chamber.

"Turn off your headlamps," Steinken said.

A curtain of darkness fell, darker than deepest space. My senses caught fire, searching like a manic cellphone for a signal, anything familiar in this utterly alien world.

Then it came. A quiet rush of wind filled the cave, perhaps from a thousand miles away. Mother Earth was breathing, and we were inside her. It was a moment I'll never forget.

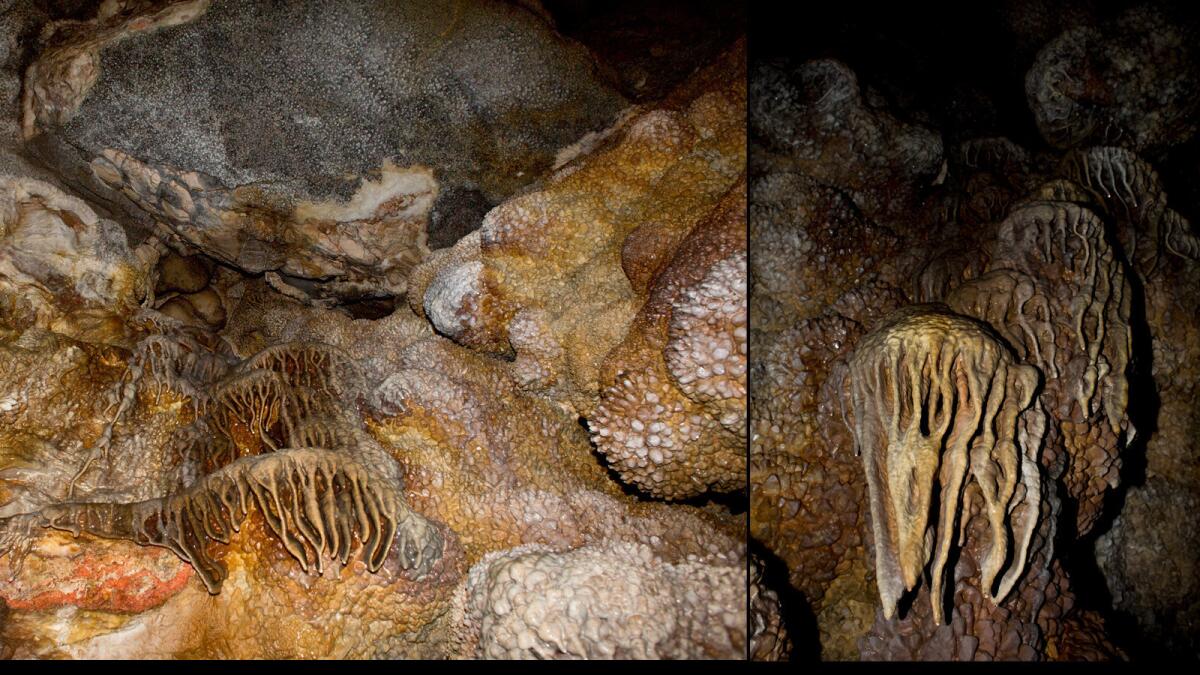

We turned our lamps back on and crawled into a massive cavern with delicate snowflake-like crystals hanging above clear pools. Caves and caverns, I learned, are the same thing. Strange silvery globules called hydromagnesite balloons clung to the walls.

From here we used a rope to climb a 30-foot boulder into an alcove.

It was Martha's Kettle. I knew that because my fellow caver, Arthur Turner, 23, had done the trip before and was visibly excited.

"It's just," he said, pausing, "intense."

I stepped on a rock nob and struggled up a narrow chimney, angling my head through an opening perhaps 8 inches high while trying not to slide back down the chute. Turner did it on his back.

"That was intense," he said with a grin.

We headed downward, single file on our bellies, moving like salamanders around curves. A laughably small opening lay ahead, one that would have frozen me with fear hours earlier. Now I simply put my head down and went through, coming out at Steinken's feet.

"That was the Brain Drain," he said. "The box outside the visitor's center is an almost exact replica."

It was over. I was filthy but buoyant.

I've explored jungles and deserts, climbed mountains and jumped from airplanes but never experienced anything as unique. And I never confronted a fear quite so head-on.

An easier way to experience Jewel Cave’s timeless mystery

A day after finishing the mentally and physically challenging Wild Caving Tour, my son and I returned to Jewel Cave National Monument for a gentler journey beneath the Black Hills of South Dakota.

We rode the elevator 239 feet down to the main chamber of the third-longest cave on Earth. It was a cool 49 degrees, a temperature that remains constant year-round.

Ranger Brad Yoder led about a dozen of us deeper and deeper into the caverns. Dimly lighted passages wound beneath ceilings more than 200 feet high. Mineral-rich water dripped from the limestone, forming delicate ice crystals resembling snowflakes. There were small stalactites and clear pools.

Jewel is currently 180.04 miles long, a length that changes every year as volunteers uncover new passages. Park officials say the cave holds 8 billion cubic feet of air, meaning it may extend a mind-blowing 5,000 miles.

We were on the Scenic Tour, a half-mile loop including 723 stair steps that showcase some of the best features of the cave.

Perhaps the most striking aspect of the cave isn't its sometimes eccentric geology, but its age.

"The first passages formed 100 million years ago," Yoder told us as we gathered in a huge room festooned with formations resembling giant squids. "The majority formed 65 million years ago."

He said the Black Hills above us were 1.8 billion years old, one of the most ancient mountain ranges on Earth.

We moved along walkways, stopping to observe dog-spar crystals resembling canine teeth. Sometimes you could hear a gentle wind blowing. In other parts of Jewel, such as Hurricane Corner, winds have been clocked at more than 25 mph.

Until about 1959, no one had ventured much more than half a mile inside Jewel, the first cave designated a national monument. Explorers gradually began pushing in farther and farther, finding passages, chutes and enormous crystal-packed chambers.

Perhaps the most intrepid were Jan and the late Herb Conn, who discovered and mapped more than 60 miles of Jewel, including the route we were on now. An exit to the cave has never been found.

I didn't experience claustrophobia on this tour, mostly because it went through spacious rock rooms. There was none of the belly-crawling required on the Wild Caving Tour.

I didn't see wildlife either, which isn't surprising. Caves are cold, barren, food-poor places where only the most specialized creatures can survive, and they are often tiny. In summer, nine species of bat live near the cave entrance.

After about 90 minutes, we returned to the visitors center.

Jewel Cave is a vast and special place where you can choose your own adventure. For me, combining this more relaxed walk with the hyper-intense Wild Caving Tour allowed me to fully appreciate the mysteries of Jewel.

Even more, it helped me understand the powerful spell caves have cast over humanity for uncounted thousands of years.

Wind Cave is a freaky maze

Wind Cave National Park, S.D.—As we were driving into Wind Cave National Park on a sunny November day, I lurched to a stop a few feet from a mighty bison astride the highway.

Where to find the nearly 5,000 caves managed by the National Park Service

Out of the thousands of caves the park service manages, only about a dozen offer tours. Here are locations by cave category:

I won't call it a showdown because that implies a Prius stood a chance against a truck-sized ungulate with belligerent eyes. So my 19-year-old son Nicholas and I waited until the beast grudgingly moved.

It was a fitting, if sudden, introduction to the myriad natural wonders aboveground in a park best known for the delights lying below.

Wind Cave, with 145 miles of passages, is the sixth-longest cave on Earth and is just 30 miles from Jewel Cave, the third-longest. If you visit one, go see the other because they offer very different experiences. Some experts think the caves might intersect at some point, though it's never been proved.

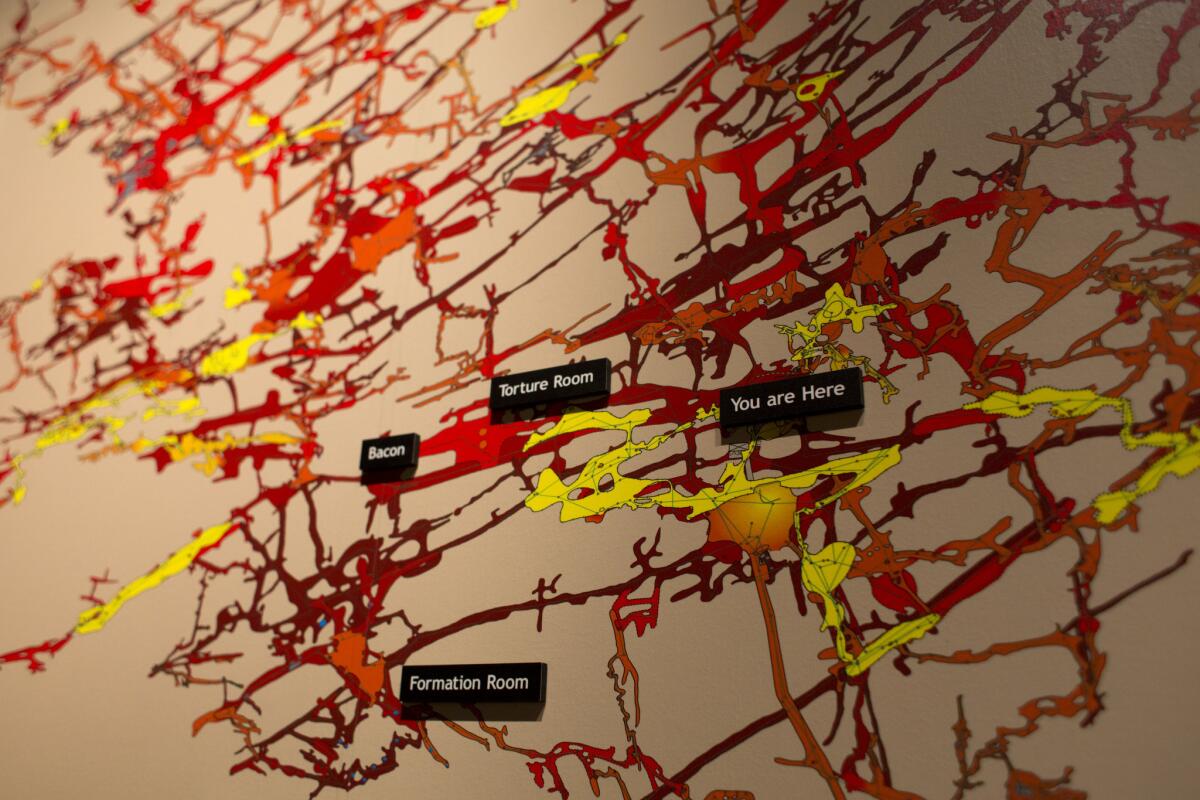

Wind is a maze, an intricate web of passageways that some geologists think is more complex than Jewel. Tunnels and corridors are stacked atop one another. Of the 145 miles explored, most are within a single square mile. Geologists compare it to a sponge riven with shafts.

The cave is also home to six underground lakes, including one measuring 200 feet long, 50 feet wide and 28 feet deep. Much of this is off-limits to visitors.

We visited in late fall when the park was nearly empty. Some of the better excursions were closed for the season, so we went on the Garden of Eden tour.

Our guide was Lindsey Gottwig, a delightful young ranger who gathered us into an elevator and took us down to the main cave chamber.

"When they first discovered the cave it was advertised as the Great Freak of Nature," she told us.

In 1881 Jesse and Tom Bingham came across a hole maybe a foot across with wind blowing out of it. The cave was discovered shortly after and in 1890 was opened for visitors.

We took a short walk through caverns carved over 350 million years by naturally occurring carbonic acid, which gradually dissolved the rock.

Wind Cave is home to 95% of the world's boxwork, intersecting honeycombs of calcite blades and fins that form on cave walls.

Early explorers thought they resembled post-office boxes and named them accordingly, dropping the "post office" for brevity.

We also found delicate, clear needles of calcite called frostwork hanging from the ceiling. There were also gypsum flowers and cave popcorn, calcite beads on the ceiling.

The park offers a variety of tours during summer, spring and fall, including the Natural Entrance Cave Tour, the Fairgrounds Cave Tour, Candlelight tour and the Wild Cave tour.

After returning to the surface, we drove through the park looking for pronghorn antelope and elk. We encountered more of the park's nearly 500 bison grazing in the straw-colored grasslands, including our surly friend from earlier that morning.

We exchanged glances before driving back to Custer, S.D., for dinner.

I had the bison burger.

Tips for Visitors

How to get there

Rapid City Regional Airport in Rapid City, S.D., is the nearest airport. Jewel Cave National Monument is 63 miles away; Wind Cave National Park is 69 miles away.

Best time to visit

Cave tours are available year-round at Jewel Cave National Monument, but days and times are limited through mid-March. In summer, tours often sell out early. Reservations accepted only for the Wild Caving Tour ($31). Wind Cave has tours year-round, but the greatest variety is offered in spring and summer (Tuesdays and Wednesdays are the busiest days).

Accessibility

Jewel Cave has a number of services for those with disabilities. Limited areas of Wind Cave are wheelchair-accessible. For info on tours for those with limited mobility or for the hearing-impaired.

Know yourself

Cave tours can be mentally and physically challenging. The most popular tours at Jewel and Wind take place in spaces that are mostly wide open. You won't crawl through any tight spaces, and any reasonably fit person can handle the flights of stairs. But think hard about trying the Wild Caving Tour at Jewel if you are claustrophobic or inclined to panic (deep breathing helps). The rangers won't let you go unless you can crawl through an 8.5-by-24-inch box at the visitors center. There are no exceptions.

What to wear

Its usually about 49 degrees in these caves, so wear a sweater. Boots are recommended to avoid slipping on wet rock. Those on the Wild Caving Tour will need a complete change of clothes and another pair of shoes to wear when leaving because the rangers won't let you walk through the visitor center floor in filthy boots. Your clothes will be ruined by black manganese that will cover you head to toe, so wear a long-sleeve T-shirt and jeans you won't mind ditching when you're done. Also, if you have visited other caves recently, rangers may ask you to store your shoes, coats, boots or any other article of clothing in your car to help stop the spread of white-nose syndrome, an infectious disease that is killing millions of bats.

Photo tip

You are free to take photos, but tripods aren't allowed. On the most popular tours, the most scenic rock formations are often softly illuminated, which helps. Taking a camera on the Wild Caving Tour would be a challenge, but one person in our group used a GoPro camera mounted on his helmet.

Sleep

Rocket Motel, 211 Mt. Rushmore Road, Custer, S.D.; [605] 673-4401. Comfortable, clean, retro-themed motel about 13 miles from Jewel Cave National Monument. Wind Cave National Park has one campground.

Eat

Buglin' Bull Restaurant and Sports Bar, 511 Mt. Rushmore Road, Custer, S.D.; (605) 673-4477. Outstanding buffalo burgers along with steaks, fish and salads.

More info

Jewel Cave National Monument website; Wind Cave National Park website

Follow our adventures: Facebook | Twitter | Pinterest

Additional Credits: Digital design and production: Sean Greene.

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.