Postcards From the West: In Katmai National Park, Alaska, up close with bears pursuing salmon

A visit to Katmai National Park in Alaska to see the coastal brown bear pursue salmon.

Reporting from Katmai National Park, Alaska — In the Alaska of my mind, it is always summer. A bear stands hip-deep in glacial runoff, swatting salmon and swallowing them whole. Eagles wheel overhead. Moose meander in the bush. The theme from “Northern Exposure” echoes across the tundra.

The real Alaska falls short of this. It has four seasons, high prices, treacherous weather, nasty arguments over mineral extraction and a finite number of places where a human can safely peek over a bear’s shoulder.

But those places do exist. Katmai National Park is one. When a rare overnight opening popped up, I jumped. Four months later, in mid-July, Times photographer Mark Boster and I headed to Katmai’s Brooks Camp to see what bear-salmon reality looks like.

Stage 1 was a jet to Anchorage. Stage 2 was a 30-seat plane to King Salmon (population 374), gateway to Katmai. Stage 3 — because you can’t reach Brooks Camp by road — was a 35-mile hop in a De Havilland Canada DHC-3 Otter floatplane, which gently settled on glassy Naknek Lake and glided to shore. We stepped straight from pontoon to plank to the pebbly beach.

We were 290 miles southwest of Anchorage, undistracted by cellphone reception or Wi-Fi. Even though we had soared across a near-infinity of volcanoes, lakes and glaciers, we were entering a small world unto itself.

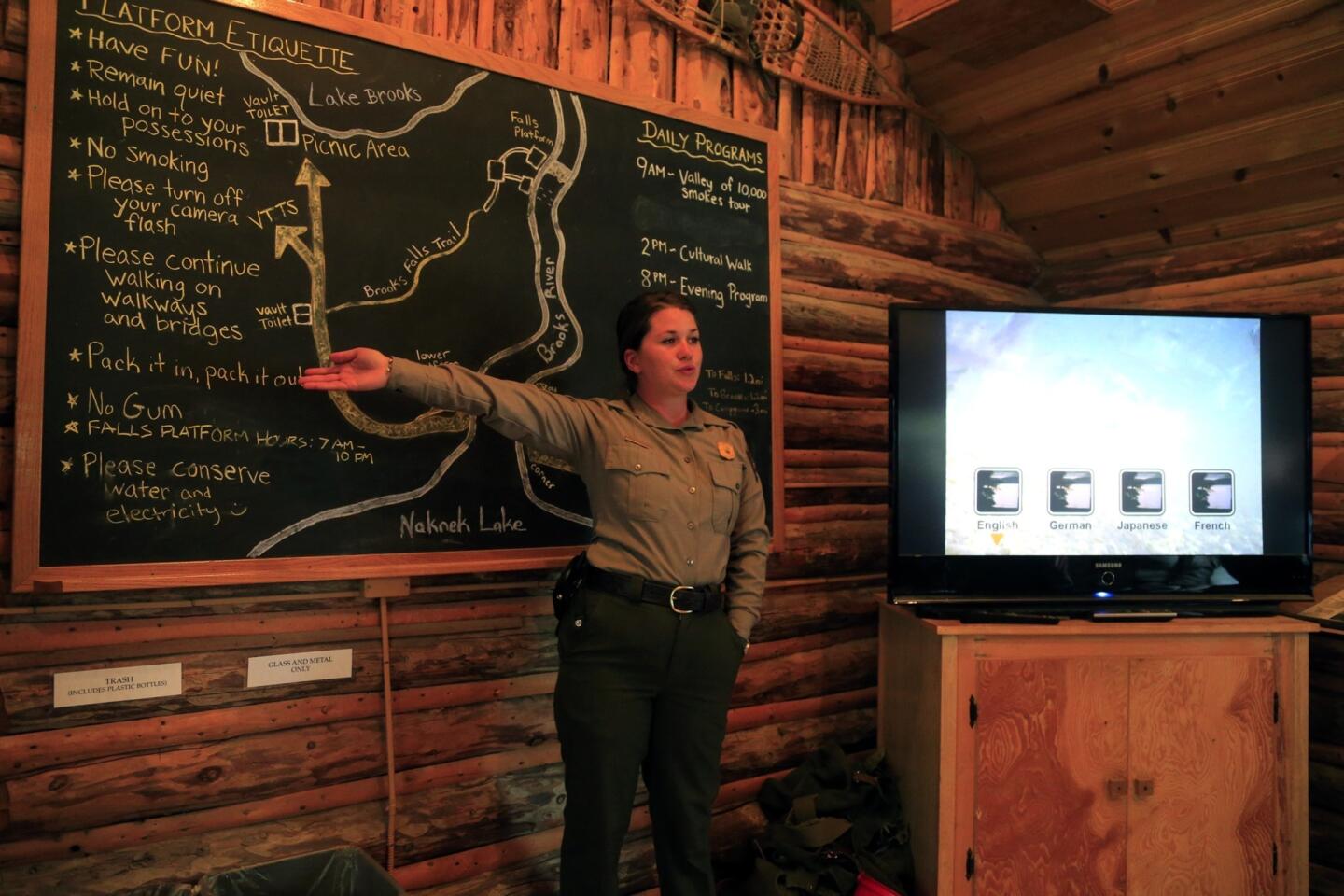

The beach is short, with half a dozen floatplanes tied up like horses outside a saloon. New arrivals are routed into a snug park visitor center for a ranger briefing and video on safety and the habits of the coastal brown bear, which is the same species as the grizzly but bigger, more tolerant of humans and, if the season is summer, ravenous for salmon.

Brooks Camp is basically a main lodge and cafeteria, 16 lodge cabins (which hold up to 60 guests) and a modest campground (surrounded by electrified fence) that holds 60 tent-dwellers. From the visitor center it’s less than a mile up the trail to the Brooks River, which is really a brief stream between two lakes, barely 1 1/2 miles long with a lively 5-foot waterfall near its midpoint.

In June and August, Brooks Camp is all about fly-fishing. But in July, when the salmon typically buck the current to spawn above Brooks Falls, bear-watchers and nature photographers show up from all over. In September, when fall color arrives, you see a mix of anglers and photographers.

Within an hour of reaching camp, I heard French, German, Italian, Japanese and Mandarin (and two Irish brogues). Within 90 minutes, I had spotted my first bear. It was a male, lazing in a water hole like a golden retriever off leash, perhaps 150 yards from the main lodge. The buffet workers and veteran guests just shrugged. Soon I understood why.

There are three viewing platforms within 1.2 miles of the lodge. The nearest, just across the Brooks River Bridge, is the Lower River Platform. Next comes the Riffles Platform, overlooking a wide, flat stretch of the river that’s favored by mama bears and their cubs. And then, just a little farther, there’s the prime spot, the Falls Platform, which holds 40 people at a time and is open from 7 a.m. to 10 p.m.

That first afternoon, I arrived there to find a ranger standing at the gate like a maitre d’, waiting list in hand, headset on.

“Reynolds, party of two,” I said.

“It’s at least a 40-minute wait. Maybe an hour,” he said. At which point the Alaska of my mind began to resemble a Houston’s restaurant on a Saturday night.

When my name was called, I strolled into a scene that was one-third “Animal Planet,” one-third presidential news conference and one-third “Waiting for Godot.” The river and falls were gorgeous. The bears were fearsome and quirky. Every sudden move among them sparked a burst of shutter clicks on the platform. But for long minutes, the fish would lie low and the bears would stand like statues, waiting.

Why? The sockeye salmon had started spawning earlier than expected, and most had already made the journey up the falls. So the bears were seeing perhaps one leaping sockeye every few minutes instead of the 100 a minute they see during the peak days of summer. And they were still hungry.

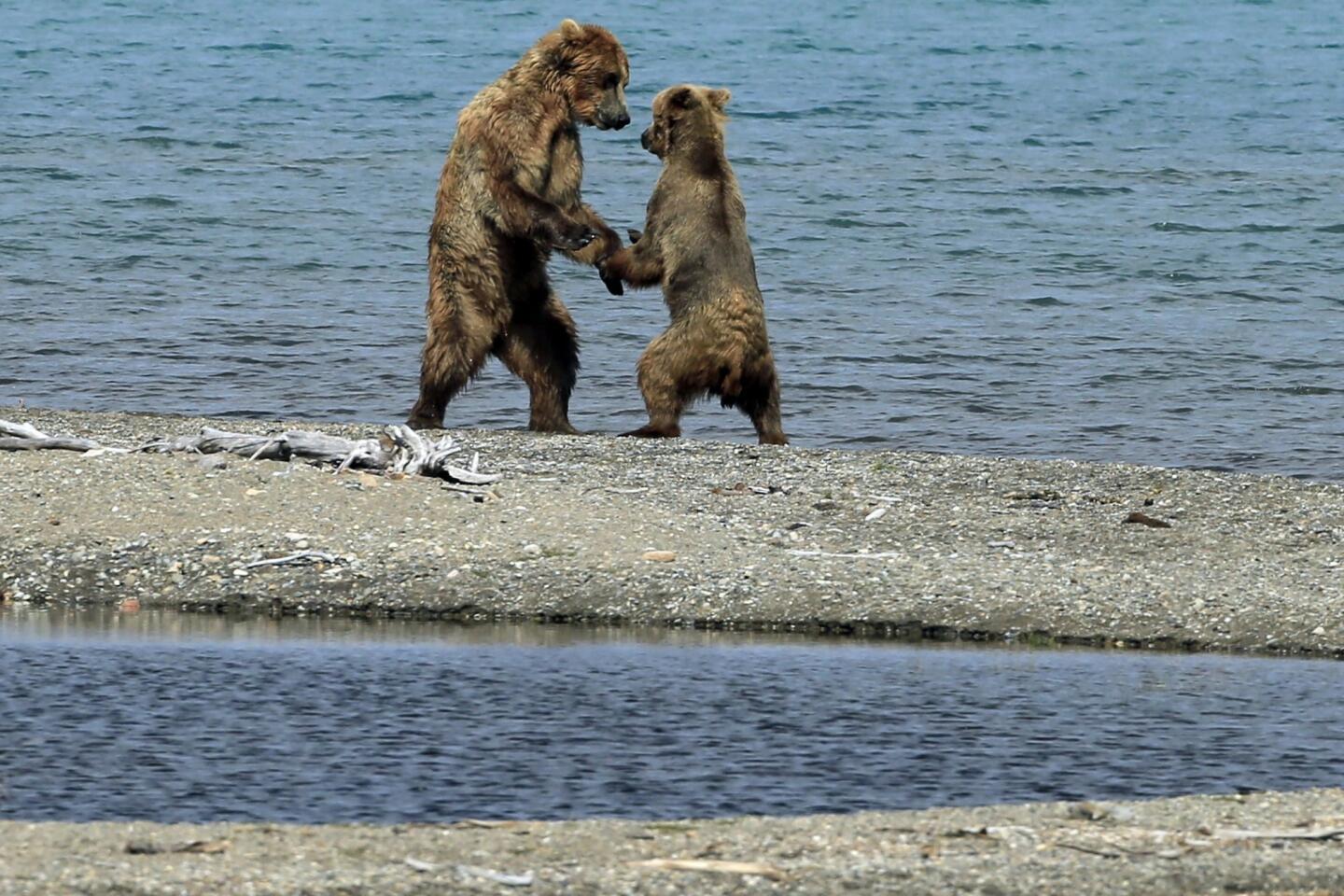

We watched them wait, pounce, rise on two legs to look around or growl and swipe at one another. One youngster leaped at birds on the beach. Two more playfully swatted each other in the shallows of the lake for close to an hour. The old bears never did that. They would trap a 6-pound salmon beneath a meaty claw, then drag it out of the water to gnaw on it elsewhere — sometimes right beneath our platform.

The bears’ body language seemed so human, I thought. I completely understand the appeal of the Internet bear cams set up along the river and all the nicknames these bears have accrued. Romeo. Juliet. Otis, Lurch, Big Ears Blondie.

But then I would catch that unamused omnivore look in an adult male’s eyes. His life depends on ingesting a year’s worth of calories in six months. Mostly it’s salmon, but not always. Sometimes the big male bears kill little ones and eat them. Yet among human visitors, rangers say, they haven’t had a significant bear-related injury in more than 15 years.

Off the platforms, you’re ordered to keep 50 yards from the nearest bear. (In Denali National Park — which registered its first bear-mauling fatality in 2012, when a grizzly attacked a 49-year-old hiker from San Diego — the minimum distance is 300 yards.)

But the bears didn’t get that memo, and they roam everywhere — down the trail, up the beach, just outside the lodge bathroom door. About 30 rangers (including many seasonal hires and volunteers) circulate constantly, barking bear positions into walkie-talkies and often instructing visitors to hold still or back off as bears blithely pass 10 or 20 yards away. The delays are called bear jams.

“Sub-adult is running toward point,” a ranger at the Lower River Platform will say, holding a gaggle of antsy photographers in place. And then: “Sub-adult has disappeared.”

“Brooks Camp is an ironic place,” said Mike Fitz, a National Park Service visual information specialist who runs the bear cams. “You come here to see bears. But often you can’t go where you want to go, because bears are in the way.”

The rangers try to use numbers instead of names for the animals. They counted about 50 bears along the river in July 2013, closer to 30 this July. For at least three summers, the dominant bear has been 856, which is in its mid-teens, weighs close to 900 pounds and has remarkably few scars. If you want to see scars, just check out the bears that got in 856’s way.

The whole enterprise hangs in a delicate balance; it’s a great credit to the concessionaire and the rangers that Brooks Camp hasn’t had a bear-related injury in many years, and never a fatality. But the wider its popularity spreads, the trickier safety becomes.

Though the park service has dubbed its bear-safety video into German, French and Japanese, the rangers didn’t have a Mandarin version (or a Mandarin-speaking ranger) during my visit. Meanwhile, Chinese visitors are on the upswing, and groups often arrive without much knowledge of English or experience with 1,000-pound predators.

One morning, an angry young ranger ran past me on the trail, chasing five Chinese men who were too close to a bear and deliberately getting closer.

“I’m going to give them a talking to,” the ranger said.

Either the park service or the Chinese tour companies need to find a better remedy here or somebody is going to get hurt.

By my final morning at Brooks, I had seen one bald eagle and no moose. I had tested the cafeteria crew’s patience by showing up late to dinner twice. I thought I had become accustomed to this little universe.

But then, tiptoeing out to the empty beach before the first floatplane was due, I glanced up the shore. A young adult bear was padding along the sand straight at me. It was about 50 yards away — not nearly as close as others I had encountered on the trail or seen from platforms. But the scene was otherwise so still and empty and perfect that the moment sunk deep. Wonder. Fear. Damp foliage. Wet fur.

And then a ranger materialized, whispered into his walkie-talkie and diplomatically nudged me away until the coast was clear.

_______

Key points in history for Katmai National Park in Alaska

Circa 2,500 BC The first humans arrive in the Brooks River area of Alaska, about 290 miles southwest of where Anchorage will grow.

1700s Russian explorers, reaching the area, find that the native people, the Savonoski and Sugpiaq/Alutiiq, have devised half-underground dwellings known as barabaras.

1912 Novarupta, about 30 miles southeast of the Brooks River, erupts for 60 hours, spewing about 6 cubic miles of ash. The U.S. Geological Survey will call this the most voluminous volcanic eruption of the 20th century. Volcanic flow buries 40 square miles of the smoldering Ukak Valley, which soon has a new nickname: the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes.

1918 Katmai National Monument is established to preserve the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes. But Katmai is so remote and visitors are so rare that the National Park Service doesn’t station a ranger at the scene.

1931 Katmai National Monument is expanded to include the Brooks River area, protecting habitat for brown bears, moose and other wildlife. (Other additions follow in 1942, 1969 and 1978.)

1950 Alaska aviation pioneer Ray Petersen secures a park service concession to open five Angler’s Paradise fishing lodges, including the Brooks Lodge at Brooks Camp. Trout are the big draw for most fly-fishers, with most of the action along the Brooks River. Lodge rates are $25 per day, meals included. To cope with the influx, the park service assigns Brooks its first ranger.

1959 Alaska statehood.

1960s Cabins replace tents at Brooks Lodge, and a road is completed between Brooks Camp and the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes, allowing day trips to the valley. Some say it’s 22 miles, some say 23.

1980 Katmai is promoted from national monument to national park. It now amounts to 3.7 million acres, with more acreage than the Grand Canyon and Yellowstone combined. Visitors can get there only by boat or floatplane.

1988 Nature photographer Thomas D. Mangelsen captures a bear standing atop Brooks Falls, about to snap his jaws shut on an airborne sockeye salmon. The shot, titled “Catch of the Day,” becomes one of Mangelsen’s most popular images.

1993 Katmai tallies a record 53,421 visitors for the year. Brooks Camp is the leading attraction.

2003 After more than a decade of defying and evading rangers with his efforts to get close to the bears of Katmai, amateur naturalist Timothy Treadwell is fatally attacked along with his girlfriend, Amie Huguenard, at their camp on Kaflia Bay, about 50 miles southeast of Brooks Camp. They are the only known human deaths by bear in the history of the park. (Treadwell’s story is told in the 2005 Werner Herzog documentary “Grizzly Man.”)

2007 A Katmai park attendance record: 82,634 visitors for the year. As the park’s fame spreads, more visitors come from Europe and Asia.

2012 Brooks Camp starts live bear cam Internet feeds showing Brooks Falls and nearby sites. Accessible at 1.usa.gov/W0UAY5 and bit.ly/1l4L7WY

2013 National Park Service counts 28,966 recreational visitors to Katmai, about half of them during July. Brooks Lodge is now operated by Katmailand Inc., whose top executive is Sonny Petersen, Ray’s son.

Sources: National Park Service, www.nps.gov; U.S. Geological Survey, pubs.usgs.gov; Katmailand Inc., katmailand.com.

_______

A hike up Dumpling Mountain reveals grandeur of the Alaskan landscape

I couldn’t tear myself away from the Brooks River bears for the eight hours it would have taken to visit the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes, which is still buried in volcanic ash from the great Novarupta eruption of 1912.

But I did like the idea of climbing Dumpling Mountain.

From the trailhead at Brooks Campground, it’s 1 1/2 miles of steady climbing, with an elevation gain of 800 feet, to a dramatic overlook on the mountainside. Rangers call it a “moderate to strenuous” route, full of blue and purple flowers (arctic lupine and wild geranium) and occasional red berries (lingonberries). If you’re game, you can continue 2 1/2 more miles to the top of the mountain, well above the timberline at 2,440 feet above sea level.

The foliage is thick at first, so there’s plenty of bushwhacking. In fact, the hiking is like skiing in powder: You know your feet are down there somewhere beneath all that natural material, but you might not see them for a while.

You also might not see other people. I saw only one other hiker on the way up and one on the way down. As a result, I made sure to watch for bears and make noise. Though rangers say the slopes are full of well-hidden dens where bears will settle in to hibernate, I didn’t see a single bear on the mountain — just tree stumps that could have been. That kept me alert.

As you gain altitude, the foliage thins, the views widen and, after 45 to 60 minutes, you find yourself at the first overlook, gazing down at Naknek Lake, which might be silver or turquoise depending on Katmai’s ever-changing skies. (It’s cloudy four days of every five in summer, but the clouds come in infinite variety.)

After five more minutes or so, you reach the second overlook, where you can see the panorama of Naknek Lake, Lake Brooks and the slender 1 1/2-mile ribbon of Brooks River in between them. The floatplanes buzz like dragonflies down below. Snowcapped mountains crowd the horizon, and you are reminded that this is but a tiny sliver of a 3.7-million-acre park and that the park is but one of eight national parks in the state. There’s no way to overestimate the grandeur of the Alaskan landscape — as your plane ride back to Anchorage will remind you.

_______

Marking visit to Alaska’s Katmai National Park as mission accomplished

Out in the water at Brooks Falls, the bears were doing their thing. Up on the viewing platform among the telephoto lenses, two off-duty executives from Chicago turned from their cameras to explain themselves.

“It’s about seeing the animal in its natural habitat, doing what it does every day,” Amy Marta said.

“Have you done the orangutans?” Ruey Tu asked me.

Marta, 44, and Tu, 53, have been a couple for 24 years. For almost as long, they have been choosing trips that showcase animals and fragile environments. Though they rarely take more than three weeks’ vacation per year from their jobs, they’ve seen and photographed enough exotic beasts to fill an ample zoo.

Polar bears at Churchill, Canada. Mountain gorillas in Rwanda. Gray whales in Baja California’s San Ignacio Lagoon and sea turtle hatchlings at Cabo San Lucas. Manta rays off the Big Island of Hawaii. Humpback whales off Maui. Orangutans and Komodo dragons in Indonesia. Stingrays off Grand Cayman in the Caribbean. Penguins in Antarctica. Koalas, kangaroos and platypus (apparently, nobody in the know says platypi) in Australia.

They have done African safaris (Tanzania, Botswana) and the Galápagos. Later this year, India for tigers.

Marta, raised in Wisconsin, grew up taking national park trips with her family every summer. Tu, whose parents left China in 1948, was born and raised in Michigan. His family had an international outlook and spent nine months in Taiwan in 1967, which left him eager to see more of the world.

They earn a good living, but another key to affording and making all these trips, they say, is careful planning, bargain-hunting, flexibility and patience. In fact, they have agreed to wait on most big cities and “cultural destinations” until after they’ve hit their targets in the natural world.

Because Tu travels for his job in the pharmaceutical industry (often to Paris, one of his least favorite places), the two can usually buy their flights with frequent-flier miles. Whenever possible, they do without tour operators or other intermediaries.

“Like Rwanda,” Marta said. “You can do it alone. Twenty years ago, you didn’t have a prayer.”

“Our friends think we’re crazy,” Tu conceded. But “we have a travel philosophy: to try to go places that are rapidly changing and that are unlikely to be the same in 10 years.”

They keep an eye on charity auctions, where far-flung trips can sell at deep discounts. They stay flexible; they secured their Brooks reservations only after a cancellation came up two months before the arrival date. And they keep their options open.

Marta, a sales and marketing consultant, tracks their travel ambitions on a wish-list spreadsheet that charts animals, destinations and seasons. Pandas in China? Harp seals in Canada? Monarch butterflies in Mexico, chimpanzees in Uganda? The fireflies of the Great Smoky Mountains, which can synchronize their flashing light patterns? All on the list.

In 10 or 20 or 30 years, “Big Ben will still be there,” Tu said. But these beasts may not.

As for the bears of Katmai, Marta and Tu headed home with mixed feelings. They saw plenty of bears and plenty of scenery. But if you set aside airfares, they said, Brooks Lodge was the priciest place they have been, about $400 per person per day for meals and lodging. And because the 2014 salmon run started early, there were fewer fish jumping during their stay, thus fewer photo ops.

“If I’d come in as a day-tripper,” Tu said one afternoon, “this would have been a skunk.”

And that, of course, is one critter they can do without.

_______

Do’s and don’ts when visiting Katmai National Park in Alaska

When in the Brooks Camp part of Alaska’s Katmai National Park, do spend hours on the Brooks Falls platform. But don’t expect them to be all in a row. There’s room for only 40 people on that platform. When it’s busy, rangers limit visitors to an hour per session and keep a sign-up list. Park info: www.nps.gov/katm. Brooks Camp concessionaire info: katmailand.com.

Do bring a long lens. Most serious photographers at Brooks come armed with 300-millimeter lenses or more, along with a tripod or monopod. If you’re not ready for that investment, many photo shops rent equipment.

Don’t give up if all the beds and campsites are taken. You can do Brooks Falls as a day trip from Anchorage: You’ll be on a tight schedule, you’ll be elbow-to-elbow with a crowd of photographers and bear-watchers, and it’ll cost you a pretty penny. This year’s tab for round-trip airfare is $669 person, offered by Katmailand Inc., the concessionaire that runs Brooks Lodge.

100 yards east of Brooks Falls: Don’t underestimate Riffles, the no-reservation-required platform just downstream from the falls platform. Female and young bears often hang out there, avoiding the aggression of the big male bears.

1 mile east: Do climb up the Lower River Platform to scan the scene before crossing the Brooks River Bridge. Bears love to linger along the banks near the bridge and at “the corner,” where the beach ends and Naknek Lake meets the river.

1.2 miles northeast: For a lodge room, do plan well ahead. Room at Brooks Lodge (capacity 60 people) can be booked 18 months ahead through katmailand.com. When the lodge opened bookings for July 2015 on Jan. 2, 2014, rooms were gone in three hours. Cancellations do pop up; that’s how I managed to book a July stay in March.

1.2 miles northeast: If you’re overnighting, do expect hefty prices. For two nights in July in a rustic lodge room for two with round-trip air, we paid $1,351 each, meals excluded. You put four people in the room (which has two bunk beds), it’s still $1,050 per person. This puts Brooks among the costliest of national park lodges. In July, there’s a three-night maximum. You won’t see many children here.

1.2 miles northeast: Don’t expect fancy food and don’t lose track of time. The lodge cafeteria serves an all-you-can-eat breakfast ($17), lunch ($22) and dinner ($35). The dinner service stops at 7:30 p.m., when the sun is still high in the sky. It’s easy to linger on a platform or get caught in a bear jam and miss the deadline.

1.2 miles northeast: Do bring strong bug spray. They don’t always bite, but insects abound. (Don’t buy a fancy headnet in advance. You can get one in the lodge shop for less than $5.)

1.2 miles northeast: Do take some time on Naknek Lake’s beach, especially in the early morning and late at night. Not only is it fun to watch floatplanes land, taxi and take off, the play of light on the water, land and clouds can be astonishing.

1.4 miles northeast: For a campsite, do plan six months ahead. Brooks Camp Campground accommodates just 60 people and is open May through October. Campsite reservations for this year opened Jan. 5 and the month of July sold out within days. For stays June 1 to Sept. 17, the cost is $12 per night per person. In May and from Sept. 18 to Oct. 31, the rate drops to $6. Info: www.recreation.gov ([877] 444-6777) or 1.usa.gov/1oYo57B

Don’t expect freedom of movement. You’re banned from taking food outside prescribed areas. Rangers often declare bear jams, ordering visitors to freeze while bears are meandering near the bridge, on the beach, on the trail or next to lodge buildings. This might last a few minutes or an hour.

Don’t worry about running out of light. In July, the sun doesn’t set until about 11 p.m. And even then, the skies look more like dusk than deep, dark night.

Twitter: @mrcsreynolds

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.