Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Since he first arrived in Los Angeles, the conversation around Caleb Williams has failed in many respects to capture the quarterback’s true nature. Every aspect of his identity — including his painted nails, his name, image and likeness portfolio, and his propensity for crying after losses — has been picked apart by an endless stream of analysts and anonymous scouts. The takes surrounding the quarterback have veered off track, creating a polarizing loop as he prepared for the NFL draft.

During two years of highs and lows at USC, Williams offered glimpses of who he is as a quarterback, with the weight of a proud program on his shoulders. There were stunning displays of near-supernatural talent as well as growing pains. Williams likely did enough to help convince the Chicago Bears to draft him with the No. 1 pick on Thursday night.

The Times looked back at some of the most telling moments of Williams’ Trojan tenure to clear up who Williams is and could possibly be as an NFL quarterback.

There are certainly more eye-popping plays on Williams’ highlight reel, but his first breathtaking deep ball at USC was a superlative example, right out of the gate, of what makes Williams special as a pure passer.

There was no need in the moment for his improvisational magic. Instead, the sophomore quarterback sat back in total control, scanned the field in Palo Alto and spotted his top receiver, Jordan Addison, streaking just past his man. With one effortless flick of the wrist, Williams uncorked a soaring pass that hit Addison in perfect stride 50 yards down the field. One broken tackle later, Addison was in the end zone.

Williams has been picked apart so much at this point, it’s easy to overlook the most fundamental part of why he’s long been considered a top NFL prospect: His arm is ridiculous. And the control he has over that cannon is something that simply can’t be taught.

Nothing was working for Williams during his sole trip to Corvallis. His timing was off. He missed open receivers. But USC’s defense forced four turnovers to keep the Trojans in the game and give Williams one shot to save the day. He didn’t disappoint.

Two dropped passes left Williams with a do-or-die fourth down. As soon as he snapped the ball, the pocket collapsed, but Williams darted through danger, dancing his way near the first-down marker, where he lowered his shoulder into two defenders. It took a nudge from his linemen to get across the marker, but Williams’ uncommon lower-body strength held him steady for just long enough.

With only a minute remaining, Williams laced a pass down the sideline to Addison. A split-second earlier, the cornerback charging the underneath receiver would’ve broken up the pass. A second later, and the safety helping cover Addison probably would’ve picked it off. But the pass arrived precisely on time, hitting Addison for a game-winning score.

“Some things are not going to go your way,” USC coach Lincoln Riley said later that night, “and how you respond in those moments is what separates you.”

Williams conjured every ounce of magic he could. But against Utah, it just wasn’t enough. As his final pass fell to the turf in Salt Lake City, ending USC’s spotless start in devastating fashion, the realization hit Williams like a ton of bricks. Leaving the field, his eyes welled up with tears.

It was the first time Williams was seen in tears while wearing a USC uniform, his eyes still red and puffy by the postgame news conference. No one was asking then what his tears said about the quarterback’s mental toughness or his ability to lead. Anyone in the auxiliary press room that night could see how much Williams had left on the field. He was totally spent.

“The beauty of Caleb,” his high school offensive coordinator, Danny Schaecter, later told The Times, “is when it hurts that deeply, he knows that’s something he can use to get back up and not let that happen again.”

USC won five in a row after that emotional post-game scene.

“It was a different mind-set than most guys have,” offensive lineman Justin Dedich said at the time. “It built a fire in us.”

Williams went absolutely nuclear after the Utah loss, dismantling one defense after another with almost comical ease. But his thrashing of Notre Dame would prove especially memorable considering how disastrously the Irish failed to contain him.

Their plan was to keep Williams in the pocket, to neutralize his legs and force him to attack through the air. He proceeded to complete 82% of his passes while rushing for three touchdowns. For most of the game, he seemed to be toying with Notre Dame’s defense.

The most demoralizing of those moments came on second-and-long, late in the third quarter. Williams spun away from one defender, circling back around the pocket before spotting a lane. He took off, slipping past one over-pursuing tackler, then another, before laying a devastating stiff arm on a third as he barreled past the first-down marker. It was a perfect encapsulation not only of his powerful running style, but another more intangible part of Williams’ oeuvre.

“The bigger the stage is,” Addison said after the game, “the bigger he’s going to play.”

Williams felt his hamstring pop at the end of a 59-yard run late in the first quarter. But with the Pac-12 title still in the balance and the College Football Playoff semifinals within reach, Williams begged Riley to keep him in the game despite his painful injury. The coach later called it “as gutsy of a performance as you’ll ever see.”

In the moment, Williams said, he tried to channel Kobe Bryant.

“I was in my head encouraging myself that the game is bigger than what I was feeling,” he said.

Williams gutted it out as well as he could on one good leg. Limping up and down the field, he still managed 361 yards and three passing touchdowns. But his injured hamstring sapped him of his superpowers, and for the second time, Williams was left in tears as time ran out against Utah.

Nonetheless, two days later, Williams hobbled his way through an event for his foundation, Caleb Cares. The first class of kids were graduating from his anti-bullying program, and he’d made a commitment to be there.

That same afternoon, he assured he’d be ready for the Cotton Bowl. Riley didn’t share the same outward confidence at the time. But a few weeks later, in Dallas, Williams threw for 462 yards and five touchdowns in a bowl loss, even with his hamstring still bothering him.

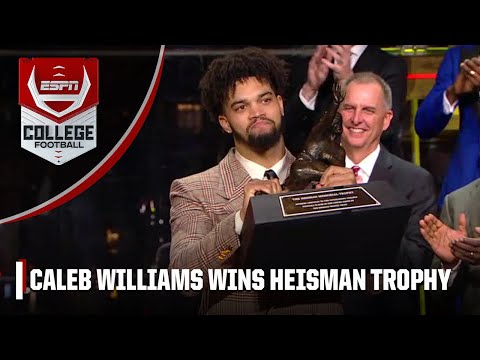

Dressed in a plaid Gucci suit, the newly crowned Heisman winner looked out into the gallery at Lincoln Center in New York, searching in the crowd for the eight enormous guests he’d brought along with him for his big night.

“My offensive linemen,” Williams said, “stand up, big guys, wherever you are.”

Heisman finalists are given few passes to bring guests to the ceremony in New York. But Williams arranged with one of his NIL partners to foot the bill and bring them all along. He didn’t want to be there, he said, if his linemen couldn’t join him.

“This doesn’t happen without each one of you,” Williams said, before listing each lineman by name.

It was a small gesture, at the end of a larger-than-life season. But for all eight linemen, it was especially meaningful. They spent that night together in a penthouse provided by the Heisman Trust, eating and laughing and reminiscing about all they’d been through.

“Being able to enjoy it with them,” Williams said, “it meant a lot to have them there.”

Williams looked out of sorts. Arizona’s defense spent the game trying to batter and confuse him.

Yet for all the passes that sailed incomplete, Williams never seemed panicked.

“He’s always had that since the first day I saw him play,” said Schaecter, his high school offensive coordinator. “Not everyone can stay cool, calm and collected when there’s a fire going on around you.”

In overtime, Williams put the offense on his back, as he so often had. He ran in one touchdown, then set up another with a second-and-19 conversion. The third overtime came down to one play for USC, and of course, Riley put the ball in Williams’ hands.

As Williams took off sprinting as hard as he could toward the pylon, it looked like he might be stopped. But, of course, Williams made it in time, reaching out as far as he could to break the plane for a walk-off win.

“When we needed him, he came through,” receiver Tahj Washington said.

In the waning moments of his worst game as USC’s quarterback, as Notre Dame fans flooded the field in South Bend, Williams kept his head down and made a beeline for the tunnel. Along the way, Notre Dame fans taunted him and shouted his name. One even recorded himself confronting the quarterback. The video went viral.

“Let me see those nails now, bro!” the fan said. Williams kept walking.

It had been a brutal night, by all accounts. Three interceptions. Six sacks. Constant pressure in a collapsing pocket. It was the second consecutive week Williams hadn’t looked like himself. Questions were already being raised about his performance: Was something wrong?

The quarterback did his best to brush off any concern: “That’s one game in the past three years that I’ve had a bad game,” he said.

“When you’re striving for greatness … you’ll have failure, you’ll have success. But doubt? Why think about it?”

The experience, after that failure, did inject some doubt into how Williams might handle taking the reins of a losing NFL franchise. Even he’d acknowledge later, in an interview after the season, that he was still learning how to stay the same person and lead through losses.

But that next week, it was clear Williams was still bothered. Asked about the fan’s viral video, Williams snarked that “everyone wants to be in these two size 12 ½ shoes right here.”

“An opinion of a sheep?” he continued. “Lions don’t worry about that, so I’ll keep moving on and keep fighting.”

The image has become a permanent fixture in the conversation around Caleb Williams: The reigning Heisman winner, leaping into the stands and curling up in his mother’s arms to cry.

It was an incredibly vulnerable moment, broadcast by ESPN for all the world to see. His mother tried to cover up the quarterback’s face with a sign for privacy. Despite her best effort, that scene has followed Williams ever since, spiraling from internet memes and sports talk debate to serious NFL front-office conversations about his future.

When Williams sat down with The Times after the season, it was clear he’d considered more deeply what that image might communicate as the face of an NFL franchise whose owner might not be thrilled with his quarterback crying in plain view.

But he wouldn’t apologize for being himself. Nor should he have. He plays football with deep feeling, in a way not many quarterbacks do. To stifle that would, in some sense, mean sapping Williams of what makes him great.

“I’m far from ashamed about showing my emotion after any of the losses this year,” Williams said. “It shows truth. It shows care. All that. I’m getting better at it, showing it in the right place and the right time. But if I won a national championship or a Super Bowl years down the line — if I was winning — nobody would be saying anything.”

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.