The Heisman Trophy winner wanders through halls of nothing in a house of nowhere.

“Fight on,” he says.

The man who ferociously rushed for more yards than anyone in USC history aimlessly meanders around the walkers and wheelchairs of his fellow residents in the memory care unit of a south Orange County assisted-living facility with one thing on his diminishing mind.

“I love USC,” he says.

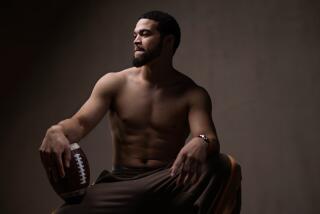

He is wearing what he wears virtually every day, Trojans gear, head to toe, from the cardinal cap to the gold shirt to the cardinal sweatpants to the cardinal-and-gold watch. He is never recognized, but that’s OK, because, for now, he still recognizes himself.

He knows he is Charles White, and he knows what he accomplished for his beloved university.

“I know I once did something good, something great, something fantastic for USC,” he says.

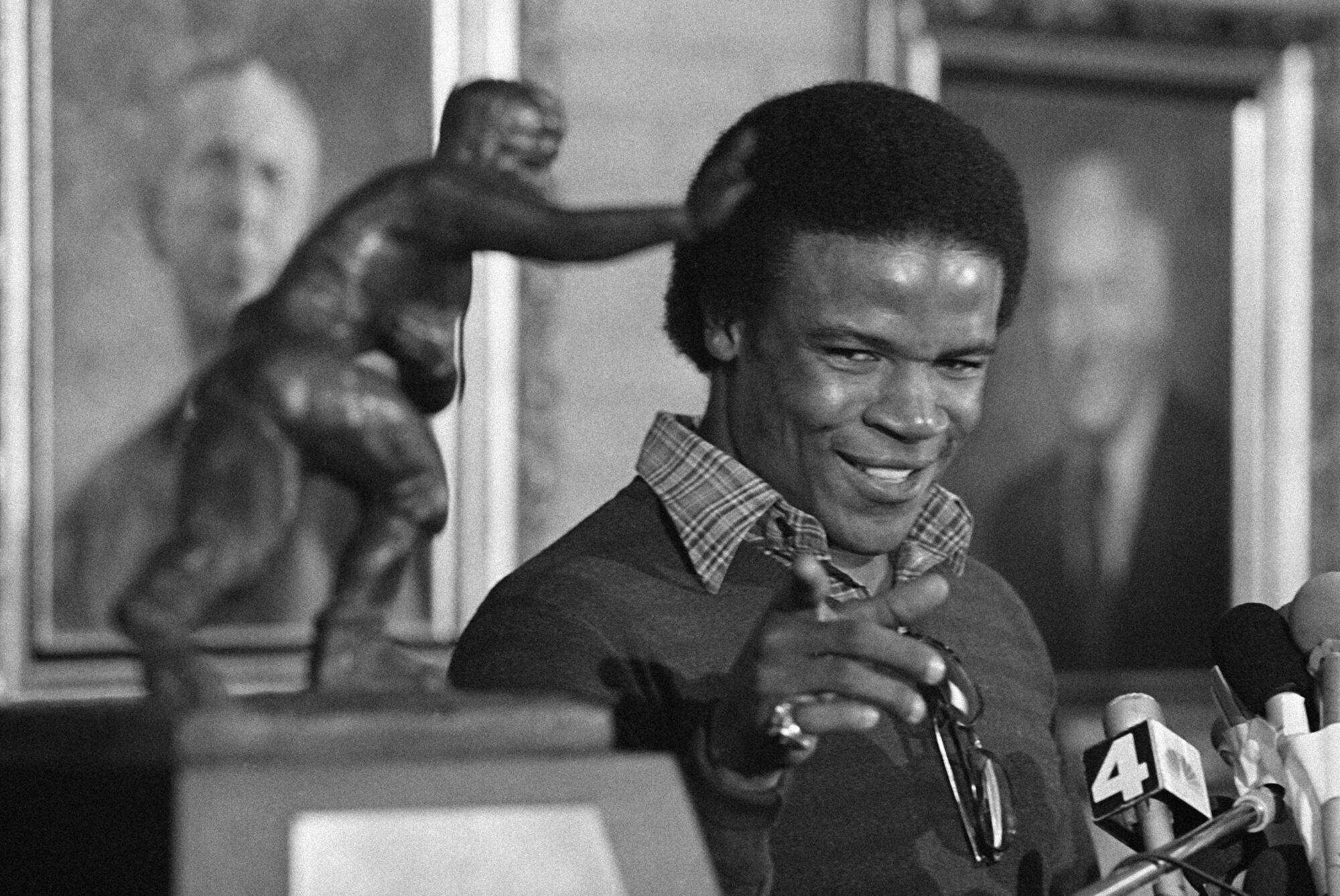

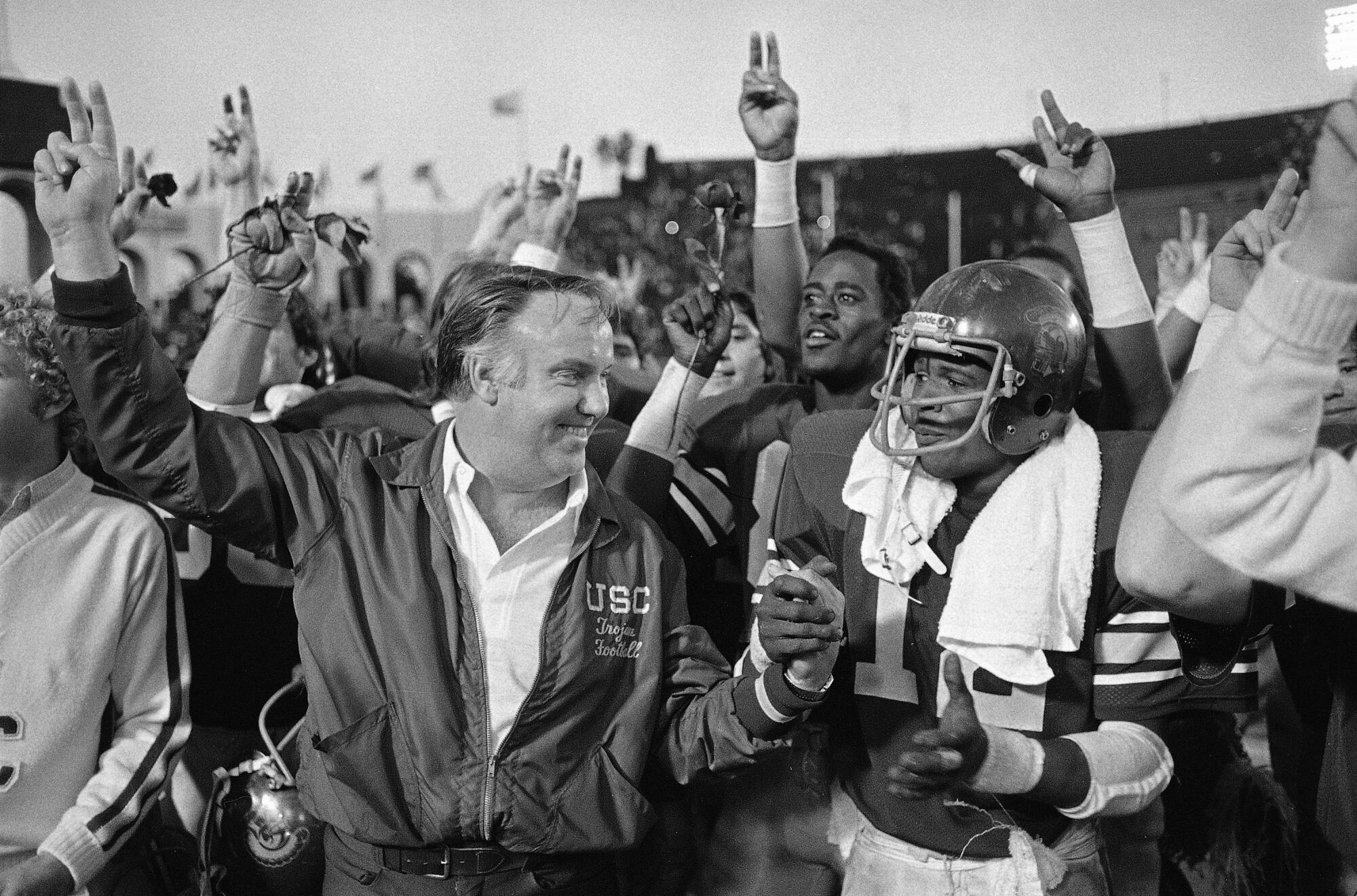

He knows he won the Heisman, was named the Rose Bowl most valuable player twice, and was a member of the 1978 national champions.

“I know it’s great because I did it,” he says.

He knows he played briefly for the Rams, even leading the NFL in rushing in 1987, but that’s not his team.

“Everything I did in football, it was all USC,” he says.

He knows he lost the trust of the Trojans family after years of drug and alcohol abuse led him to sell his Heisman, disengage from the program and become a virtual outcast.

“Sometimes I went to the devil,” he says.

Then, 10 years ago, he was diagnosed with dementia, probably caused by all those football collisions, the resulting traumatic brain injury probably contributing to his life of addiction.

This dementia has led White, 64, to this luxuriously sterile setting that his family requested remain nameless for privacy reasons. It is here that he has been living for two years virtually unseen and unknown, living behind locked door, leaving only with his family for three-times-a-week beach walks and lunch.

He doesn’t really understand his condition. He certainly doesn’t know if this dementia diagnosis will change the narrative of his Trojans legacy.

But he still knows he is Charles White, and he knows he loves cardinal and gold, and as he tucks himself in under a Trojans bed spread every night, he maintains belief that his school once again will welcome him home.

“USC forever,” he says.

The USC football program recently welcomed former stars to campus for the annual “Salute to Troy” celebration.

Charles White was not invited.

Judi White-Basch, White’s ex-wife who manages his care, recently sent an email about her husband’s condition to new coach Lincoln Riley.

She hasn’t heard back.

It has been six years since White was on campus. The family said it has been forever since anyone from the school has reached out. Over the years, when it comes to White, the football program seems to also have lost its memory.

“It’s like USC is a brother who just isn’t there anymore,” White’s daughter Tara said. “Such a big part of our life and now … nothing.”

His family knows what USC must be thinking. They know how USC generously employed White for nearly 20 years after the end of his career before his addictions led him to stop showing up for work. They understand USC’s reluctance to reengage. They hold no ill will. They’re simply hoping that once USC knows and understands what an army of doctors has confirmed, maybe the school will reconsider the relationship.

“I’m just trying to let them know what really happened to Charles,” White-Basch says. “It seems like a great time to open those doors back up. It would make him feel so good just to be invited back to Heritage Hall to say hi.”

What really happened to Charles…

To understand the magnitude of his fall, one must first understand the multitude of his hits, beginning with his first scrimmage as a 12-year-old with the Valley Chargers youth team in San Fernando. White scored six touchdowns, and spent much of the next two decades carrying the football into a maelstrom of violence.

“From that day forward, he took a lot of hits, all those years running the rock, a toll accumulated,” longtime friend Bill Settle said.

Mental health news and resources to help you cope with the stress of daily life, anxiety and more.

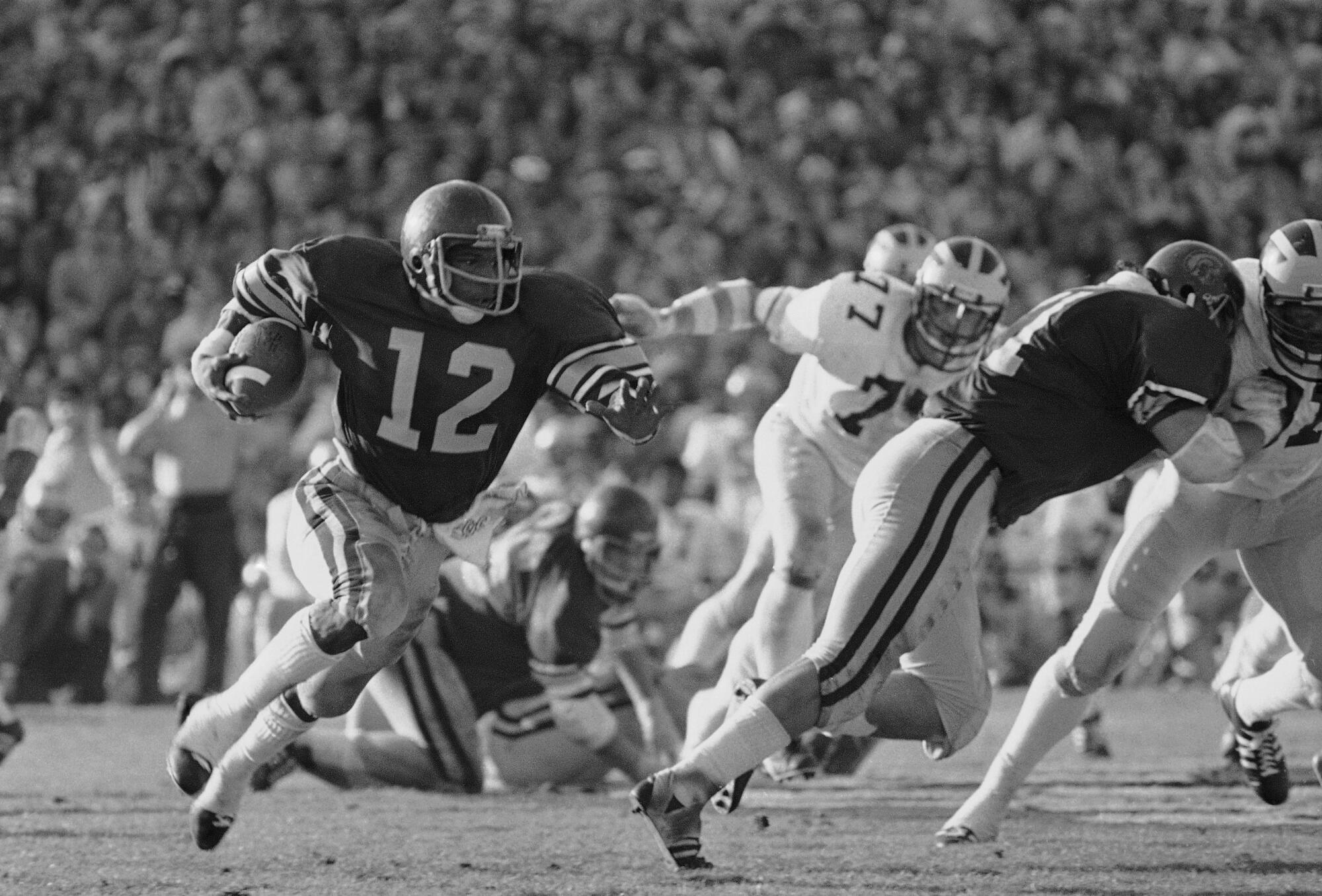

The pounding really intensified when he left San Fernando High for USC, where in four years he carried the ball 215 times more than anyone else in school history while rushing for a school-record 6,245 yards, 1,435 more than the second-place Marcus Allen.

White arguably was the greatest Trojans running back. He also was inarguably the most battered.

“Pound for pound, he was one of the toughest guys to ever play in the program,” said Paul McDonald, one of White’s quarterbacks during his four years there. “He wasn’t super fast, but he got stronger as the game went on. He would make things happen. Tough as nails, not silky smooth but so hard to bring down.”

McDonald remembers White playing with a broken nose, pancaking a safety against Notre Dame, the antithesis of the stereotypical, speedily darting great Trojans running backs.

“O.J. [Simpson] and Marcus [Allen] were slashers, while Charles wasn’t afraid just to run through somebody,” McDonald said. “He got belted in the head numerous times, but he would just go and go and go.”

White also operated with reckless abandon off the field, beginning a pattern of drug and alcohol addiction that haunted him his entire playing career.

He began smoking marijuana in high school, smoked throughout his career at USC and did his first line of cocaine shortly before the 1977 Rose Bowl. When he was with his first pro team in Cleveland, he attended drug counseling sessions with a bottle of clean urine in his pants. When he was with the Rams, there is the infamous story of a crack-induced White fending off the cops in a vacant lot with a trash-can lid.

It remains a miracle how White remained clean enough to win the rushing title in 1987. He played just one more season before washing out of the NFL and spiraling back into addiction that dogged his ensuing years at USC as a running backs coach and office worker.

Observers of his post-playing days with the Trojans felt he was just “off.” He would sleep in the locker room. He would borrow money from players. He would neglect his office duties and spend the day riding around campus on his bike.

About a year after the Trojans finally cut all ties with White, he was discovered on a curb at his apartment building. He was disoriented. He didn’t know how to get home. His family and friends thought it was the alcohol. It was 2012 and it was a turning point.

“I saw him in the hospital and said, ‘Yo, man, you can’t keep doing this, we’ve got to figure it out,’ ” Settle said.

“Everybody thought his problems were strictly drug related, now we find out that it could have been directly related to the traumatic brain injury. For so many years it didn’t make sense; now it makes sense.”

— Judi White-Basch, Charles White’s ex-wife

This painfully led to the moment they finally did figure it out. But the answer was far different from what anyone imagined.

White-Basch brought him home to live with her in Orange County, where she realized he had somehow become a child. He began disappearing, walking out the door, one night staying in the nearby woods, then later taking up residence in a neighbor’s house and wearing the neighbor’s clothes.

“It was suddenly like living in a Whac-A-Mole,” White-Basch said. “We’d handle one issue and another one would come up.”

Because he was the great Charles White, people trusted him and wanted to associate with him. He showed up at the grocery store with no wallet and somebody bought him a cart full of liquor. He bought a car without even showing a driver’s license. He contacted realtors with the promise to buy houses he couldn’t afford.

“Everybody loved him, everybody wanted to be around him, but nobody had any idea,” White-Basch said. “He had become unmanageable.”

He soon couldn’t be left alone. He would take his phone apart. He would take the TV remote control apart. He would leave the iron on. He would eat raw meat out of the refrigerator. He would retire to his room and clap and sing and talk to himself.

“It was daily trauma; it was destroying our lives,” said White-Basch, who soon realized this was about far more than the effects of lifelong addiction.

After visits with several doctors, he was diagnosed with dementia linked to a traumatic brain injury, an increasingly common affliction of former football players in White’s age group.

The family was devastated but relieved that it finally had an answer that could help explain years of erratic behavior. Studies have shown that more than 60% of traumatic brain injury patients have a history of drug and alcohol addiction, with the abuse often increasing after the initial injury.

“All we’ve been through, everybody thought his problems were strictly drug related, now we find out that it could have been directly related to the traumatic brain injury,” White-Basch said. “For so many years it didn’t make sense; now it makes sense.”

“I know the devil is still out there. But I feel safe in here.”

— Charles White, on living in a memory care facility

With help from the NFL 88 Plan, a program that assists players suffering from neurological problems, White-Basch arranged for him to be put in an assisted-living center, but COVID-19 struck, so he had to move back in with her, and the nightmare continued.

He would constantly move furniture, disappear for hours and return wearing some stranger’s shoes, stick his dinner in a drawer so he could get dessert. At one point he took a family car and drove it into the desert until he ran out of gas. Police eventually found him running on the freeway toward Barstow.

They eventually moved him into another facility, but he stole White-Basch’s wallet during the move, then scaled the fence and escaped the facility, and after four days he was asked to move.

“You see people in the NFL who are so great, then you see them living on the streets, and you wonder how?” daughter Tara said. “This is how.”

Finally, they found a quiet suburban spot where White’s life has grown calm. In the two years since he moved into his current facility, he is no longer in constant distress. His days are filled with television and family. His life is slower, simpler and suits him fine.

“I know the devil is still out there,” he said. “But I feel safe in here.”

In typical fashion, despite his limitations, he ducks his head and runs through the obstacles by placing reminders everywhere.

He has printed his resume on a lampshade next to his bed. He has printed his five children’s names on the back of a business card he carries in his pocket. He scrawled his No. 12 on the front of a straw hat.

Snapshots of his glory days, including a Sports Illustrated cover, adorn the stark, white walls of his modest room. There is a USC folding chair in the corner. One of his lone remaining trophies — a player of the game award from the 1978 victory over UCLA — sits under a table next to a portable fan.

He remembers the Rose Bowl but doesn’t remember his age. He will talk about running behind Anthony Munoz but doesn’t know the name of his facility. He watches televised football on Saturdays, but he’s not quite sure who’s playing. He hangs on to his Trojans legacy even as he slowly slips away.

“Underneath all that, he’s still Charles,” Settle said. “If you say the right words, you still get a hearty laugh out of him, you can still see the greatness.”

His family would like to share this new sort of greatness through some kind of outreach program for other families afflicted by the devastating consequences of dementia. White-Basch encourages anyone in a similar situation to contact her at [email protected].

“These players are hidden in a corner; there’s a lot of discomfort involved in being the strongest men on the planet who suddenly even can’t speak correctly,” White-Basch said. “We need to bring this out of the shadows and let these families know they’re not alone.”

White’s one big trip a year is an escorted flight to Chicago to sign autographs and supplement his income. He could handle a day trip to USC. And it turns out, he just might get one.

When Trojans athletic director Mike Bohn was contacted about this column, the door swung wide open. Bohn immediately requested contact information and welcomed a reconnection.

“Charles White’s Heisman Trophy is prominently displayed on our campus, and I know that the memories and thrills he provided live on in Trojans around the world,” Bohn said. “I look forward to learning more about the challenges in his life. The opportunity to understand our former athletes and grow with them is very important to us.”

When the Trojans Family once again sees White, they will see a lean and powerful figure with the same big smile, the same huge laugh, the same graceful stride. They will recognize him immediately. They will give him the trademark two-fingered Trojans symbol, and, even through the incoming fog, he will return the gesture, just as he is giving it now, in the quiet of this assisted-living facility, as powerfully as if he were standing in the middle of a packed Coliseum.

It is one symbol he says he never will forget because he believes it will never allow him to be forgotten.

“There it is!” the Heisman Trophy winner says, strongly sticking out both fingers on both hands, waving them in the air, the glorious memories seemingly flooding back. “All you have to do is do that, they know who you are.”

You do that, Charles White. You fight on.

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.