The kid took his finger and drew a play in the dirt. The coach who also happened to be his father eyed the play, then his son, and told him to stop it.

You don’t like my plays? I think my plays are pretty good.

To that point, D’Anton Lynn and his father had always been in lockstep when it came to the boy’s football roles. Mascot. Cheerleader. Ball boy. Peewee quarterback. That was the logical progression when your dad plays the game and his former high school sweetheart has an unplanned pregnancy his redshirt junior season at Texas Tech.

The boy followed Anthony Lynn everywhere, weaned on sidelines and in locker rooms. The biggest boosters couldn’t pay for the kind of access little D’Anton enjoyed inside Jones Stadium. His dad’s teammates pitched in, babysitting whenever the star running back who became a three-time team captain went on a date.

Curiosity about the sport came naturally as the boy grew and his father transitioned into coaching. D’Anton would flip through his father’s thick playbook, mesmerized by the Xs and Os going this way and the other. The boy drew up his own plays, scrawling one in the dirt during his first season playing the game.

A breakdown of UCLA football coaching salaries, with D’Anton Lynn becoming the Bruins’ highest-paid defensive coordinator ever.

“I was like, this is odd, you know?” remembered Anthony, who would go on to become the Chargers coach for four seasons and now serves as the San Francisco 49ers assistant head coach. “Most 7-year-olds can’t draw a play.”

After reflexively admonishing the nerve of his son — he was the coach, after all — Anthony took a closer look at the play and rendered a new verdict.

This is pretty good.

The coach wrote it down. By season’s end, it became a staple.

A quarter of a century later, with D’Anton having cycled through nearly a decade as an NFL coach before becoming UCLA’s new defensive coordinator, the 33-year-old’s roots in the profession can be traced to that finger in the dirt, the boy truly becoming his father’s son.

“He says since then,” D’Anton noted of Anthony, “he always knew I was going to coach.”

Others confuse the son for the father to this day.

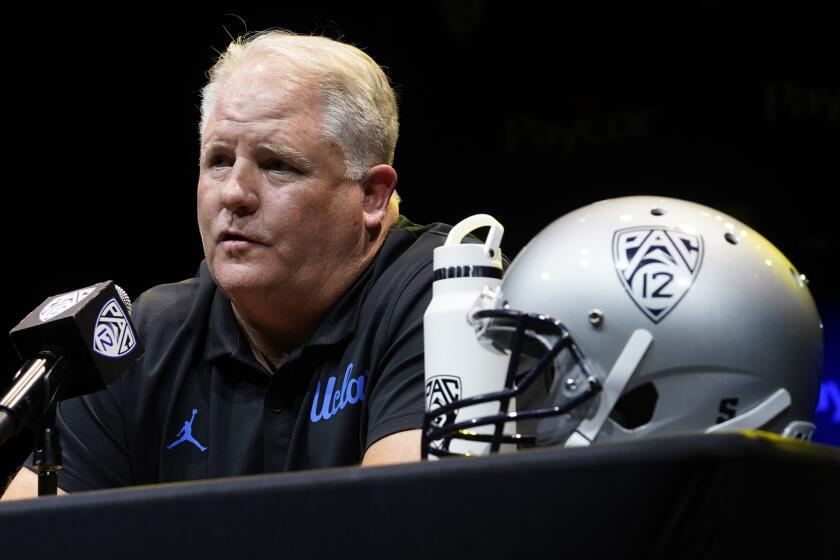

A reporter recently asked UCLA coach Chip Kelly about Anthony Lynn joining his staff, prompting a wry retort.

“Anthony’s the dad,” Kelly said. “D’Anton Lynn is the defensive coordinator.”

“This kid’s a superstar and he’s going to be, without question, a head coach probably a hell of a lot sooner than UCLA wants him to be.”

— Rex Ryan, former NFL head coach, on D’Anton Lynn

Someone needed to fill that role for the Bruins with Bill McGovern having transitioned into another position while battling the kidney cancer that took his life in May. Kelly reached out to longtime friend Bill O’Brien, the New England Patriots offensive coordinator, who mentioned how much he liked working with D’Anton when they were together several years earlier with the Houston Texans.

D’Anton had moved on to Baltimore, where he was in his second season as the team’s safeties coach. After obtaining permission to speak with D’Anton, Kelly found himself taken with his unique blend of youth and NFL experience, not to mention his ability to teach.

“He made complex things seem very simple,” Kelly said, “but he also can make simple seem complex to opposing offenses.”

Having spent his entire coaching career in the NFL, the thought of moving into the college game alongside a new set of co-workers made D’Anton uncomfortable. That was among the surest signs that he should take the job.

Fighting until the end after a kidney cancer diagnosis, UCLA defensive coordinator Bill McGovern and his family received some unexpected help along the way.

In the Lynn household, one saying is that if you’re too comfortable in any situation, there’s no opportunity for growth. If you’re comfortable and have a great spirit, some growth is possible. But great growth can only be achieved by combining discomfort with a great spirit.

This qualified.

“I just felt like I was ready to take that step and I needed to get uncomfortable,” D’Anton said, “and no matter what’s going to happen after this, I’m only going to grow.”

Those who have watched D’Anton’s rise through the coaching ranks acknowledge the unlikelihood of Westwood marking his final stop.

“This kid’s a superstar,” said Rex Ryan, the former New York Jets and Buffalo Bills coach who was D’Anton’s boss with both teams, “and he’s going to be, without question, a head coach probably a hell of a lot sooner than UCLA wants him to be.”

He was born Anthony Ray Lynn II, which might come as a surprise to some considering what everyone calls him now.

The baby was only five or six months old when Anthony’s college English teacher suggested he call his first-born child D’Anton, meaning “of Anthony.” The nickname stuck.

Once Anthony started collecting NFL paychecks, he wanted his son to try a sport that had been off-limits to him growing up in what he described as “basically a single-parent home.” Anthony put a set of golf clubs in D’Anton’s hands and watched him flourish on the course adjacent to their home.

But football always remained at the forefront for a family that savored Anthony’s back-to-back Super Bowl triumphs with the Denver Broncos. Once he transitioned to coaching with the Broncos, Anthony brought D’Anton along to practice to shag balls.

One day, Anthony glanced over in horror to see his son standing too close to coach Mike Shanahan during a nine-on-seven drill.

“I go over there and I grab him and I was like, ‘What were you thinking?’ ” Anthony remembered. “And he’s just like, ‘I wanted to see what he was seeing.’ ”

As D’Anton entered his sophomore year of high school, Anthony took a job with the Dallas Cowboys, moving back to his football-crazed hometown of Celina, Texas. That was a wrap for D’Anton’s golf career.

The son starred for the same high school football team his father had previously, landing a scholarship to Penn State. Having played five positions in high school, D’Anton specialized as a cornerback in college, becoming a three-time All-Big Ten Conference selection. A violent collision that sidelined him for two games his senior year was the first in a series of injuries that dampened his NFL draft prospects.

The New York Jets signed him as an undrafted free agent, reuniting him with his father, the team’s running backs coach. It was a short reunion. D’Anton was cut before the 2012 season, and a subsequent stay with the Hamilton Tiger-Cats of the Canadian Football League was even shorter given that he failed his physical because of a series of stingers.

Searching for direction, his playing days over, he contemplated taking an internship with a Wall Street investment firm to try something different. Then a scouting internship opened with the Jets, where his dad still coached.

“I took that instead,” D’Anton said, “and the rest is history.”

His first NFL salary was on the low end of what someone might make working at McDonald’s.

D’Anton didn’t care. Not only was he mingling with some of the top minds in his profession, but he also managed to save a third of his $21,000 pay by sleeping on an air mattress in the Jets’ practice facility.

“He said, ‘Why would I ever leave here?’ ” Anthony recalled. “ ‘I mean, I’ve got a five-star weight room and kitchen and hot tubs and spa, why would I leave this place?’ I said, ‘Because your dad is the assistant head coach — get your ass out of this building!’ ”

Ryan had watched the younger Lynn try to make the Jets’ roster fresh out of college, calling him one of the smartest players he had coached. He also proved to be one of the toughest, igniting a 20-player brawl in training camp when he shoved running back Joe McKnight out of bounds.

That put Anthony, McKnight’s position coach, in an awkward spot.

“All of our running backs were like, ‘Who were you cheering for?’ ” Ryan said with a laugh. “It never mattered who he was cheering for because D’Anton whipped the dude’s ass.”

Anthony thought his boss was just being nice whenever he praised D’Anton, but the father started hearing similar compliments from others. In 2015, D’Anton followed his father and Ryan to Buffalo as a defensive assistant. Quality time for the Lynns was surprisingly lacking.

“There were days where — I’ll be honest — we didn’t talk or I didn’t even see him,” D’Anton said of his father. “It was funny, I was running the offensive scout team for two years and it wasn’t until the second year when he was the interim head coach the last two weeks of the year that they knew he was my dad.”

D’Anton accompanied his father to Los Angeles in 2017, when Anthony received his first head coaching job with the Chargers. D’Anton became defensive coordinator Gus Bradley’s right-hand man, adding to a menagerie of mentors that now includes Romeo Crennel, Mike Vrable and Wink Martindale, among many others.

UCLA’s Chip Kelly came up with an idea to help rescue college football from it’s money-grubbing self, but it’s too logical for the sport’s power brokers.

Realizing that D’Anton was becoming a coveted commodity, Chargers management initially didn’t want him to leave when the Houston Texans called about his availability.

“I said, ‘The kid wants to get the hell away from me; he doesn’t want to walk around in this building and people think he’s only here because of me,’” Anthony said. “‘I get it. Let him go.’”

D’Anton was off to Houston to work for O’Brien, earning a promotion to secondary coach during his three years with the Texans. Baltimore then made him its safeties coach for the 2021 and 2022 seasons.

His phone was about to ring again, the next opportunity beckoning.

Two bonus clauses in D’Anton’s contract that pays him $1 million a year reflect how abysmal UCLA’s defense has been under Kelly, perhaps the biggest reason the team has gone 27-29 during the past five years despite always fielding an elite offense.

If the Bruins can assemble a top-50 defense this season, D’Anton stands to make an extra $25,000. That amount doubles if they can muster a top-25 defense.

They haven’t been close in any of Kelly’s first five seasons, topping out at No. 69 in 2020.

So what will D’Anton’s defense look like in his first season calling plays since he was a peewee quarterback? Two mantras have emerged in training camp.

“Shocking effort and taking the ball away,” defensive tackle Jay Toia said.

D’Anton would only say that his defense would play hard, attack the ball and compete from the first snap to the last.

“As far as scheme,” he said, “we’ll see on Sept. 2.”

Anyone following the team knows that’s the date of the season opener against Coastal Carolina at the Rose Bowl. Anthony predicted his son would blend what he learned from others in the NFL into a defense that maximizes the Bruins’ talent.

“He will put his own stamp on it,” Anthony said, “and I believe he’ll do well with it.”

The early returns on D’Anton’s teaching style have included adjectives such as relatable, meticulous and … slow?

“D’Anton, he loves to go slow,” safety Kenny Churchwell said, “and make sure all of this is perfection.”

Dante Moore, Ethan Garbers, Collin Schlee and Justyn Martin each had their say Saturday in how things stand in the UCLA starting quarterback battle.

That approach led to several days in spring practice when D’Anton backed off his intention to cover new concepts because he didn’t feel like players had grasped what he already taught. Listening closely wasn’t the issue given their teacher’s credentials.

“An NFL coach?” Churchwell said, wide-eyed and leaning toward the reporter asking about D’Anton’s feedback. “Whatever he says, I’m going to be like, ‘What? Yeah! I got you! What you think?’ ”

Churchwell held up his hand, signifying that practice should halt so he could listen to his defensive coordinator.

“Hold on,” Churchwell said, “stop the play.”

From his job halfway up the California coast with the 49ers, Anthony continues to support his son while also challenging him. He can only press so hard given that D’Anton recently named the baby who’s now six months old Anthony Lynn III.

Among other things, the original Anthony has told D’Anton to be himself, absorb new ideas, embrace the uncomfortable.

Like he has from his peewee days, D’Anton understands the opportunity. One might say he has his finger on it.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.