Chris Roberts, longtime UCLA basketball and football radio announcer, dies at 74

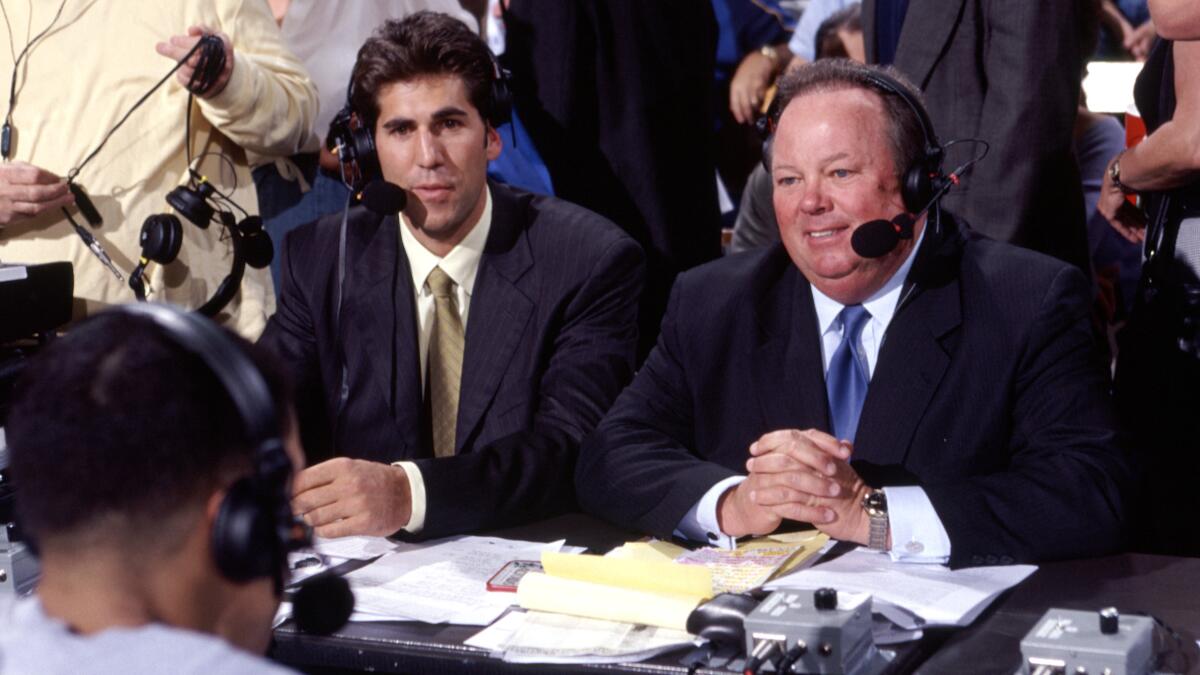

Chris Roberts had not completed his call of the most iconic play in UCLA basketball history when broadcast partner Marques Johnson butted in.

“Yeah, baby! Yeah, baby! Yeah, baby!” Johnson blurted after Tyus Edney dribbled from one baseline to the other in 4.8 seconds to beat Missouri in the 1995 NCAA tournament with a twisting layup.

“I probably stepped on his call,” Johnson remembered Saturday by telephone, “but Tyus is a cousin of mine and I went overboard and Chris gave me the latitude to do things like that. He was a giving partner.”

It was the Roberts Way, the radio voice of UCLA basketball and football for 23 years never needing to be the center of attention despite being in the middle of so many magical moments. He called two Rose Bowls and a Cotton Bowl in addition to the 1995 basketball national championship game and three more Final Fours. By the time of his retirement in 2015, Roberts had tied Fred Hessler for the longest tenure as a UCLA sports broadcaster.

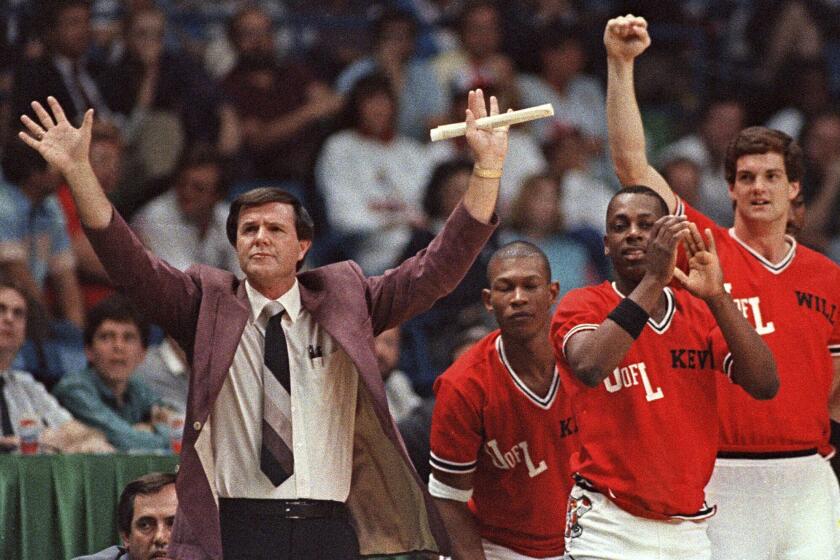

Denny Crum built a dynasty at Louisville and had chances to take a head coaching job at UCLA. The John Wooden disciple built his own story with the Cardinals.

His smooth, comforting voice having served as the soundtrack for a generation of Bruins fans, Roberts died early Friday morning at his Glendora home of complications from Parkinson’s disease and a recent stroke. He was 74.

Known for his warmth and radiant smile as much as his ability to capture the essence of games, Roberts mentored a host of broadcast partners, including Johnson, Mike Warren, Don MacLean, Tracy Murray, David Norrie, Matt Stevens and Wayne Cook.

“Without you, I’m not a radio broadcaster at UCLA,” wrote Murray, who is now the Bruins’ basketball radio analyst alongside Josh Lewin, in an Instagram tribute to Roberts. “You were my mentor, you guided me, told me to annunciate, attack the microphone… These are things I still hear in my mind when I’m broadcasting.”

Roberts’ rise was as dramatic as that of the players he covered. Born Robert LaPeer on March 23, 1949, in Alhambra, he played football, basketball and baseball at Baldwin Park High and baseball at Cal Poly Pomona, where his interest in broadcasting was sparked.

LaPeer had begun to work his way through an alphabet soup of radio stations in Southern California when the program director at KFXM in San Bernardino asked him to change his name in 1970 to avoid confusion with another station employee named Bob.

Accommodating as always, LaPeer picked Roberts as his last name because it essentially matched his first name. He went with Chris as his first name because he liked the work of sportscaster Chris Schenkel.

Formally known as Chris Roberts, he worked for several more stations while also serving as the radio voice for Long Beach State athletics for 10 years. Roberts called UCLA’s first home football game at the Rose Bowl on Sept. 11, 1982, as a member of the 49ers’ broadcast team. He worked out of a primitive radio booth consisting of a wood shed with a countertop perched atop the press box.

UCLA won in a 41-10 runaway, eventually capping that season in the Rose Bowl game, and over the years Roberts dreamed of being a part of something like that.

“If he was going to get something in L.A.,” said David LaPeer, Roberts’ son, “he wanted it to be UCLA because it was the biggest game in town in college sports.”

When Roberts was hired in 1992 to replace John Rebensdorf, a friend and former colleague who had died of heart failure, UCLA was on its fifth broadcaster in as many years. The Bruins would not have to go back on the market for more than two decades, enjoying stability during a golden age of UCLA sports.

“He was so loyal,” said Marc Dellins, the school’s former longtime sports information director. “I mean, anything that UCLA needed him to do, whether it was talk to a group of people or emcee an event, he was there, no questions asked. He was proud to represent the university and he didn’t even go to UCLA but he became UCLA.”

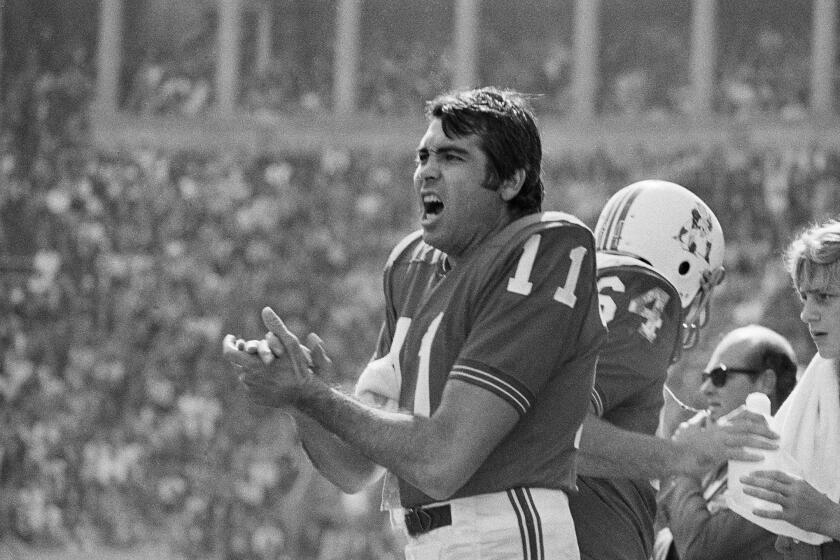

Joe Kapp, the former quarterback and coach once labeled ‘The Toughest Chicano’ by Sports Illustrated, made a big impact as a Latino role model.

On the way to becoming a four-time Golden Mike Award winner who was inducted into the Southern California Sports Broadcasters Assn. Hall of Fame in 2012, Roberts developed catchphrases such as “Uh-oh, Ed-O” whenever star forward Ed O’Bannon dazzled. He memorably described a simultaneous sack by defensive ends Mat and Dave Ball as “a twin Ball sack!”

Johnson was befuddled when Roberts would sign off broadcasts by thanking, among others, statistician Bob LaPeer. Finally, after four or five games, Johnson inquired about this mysterious Bob LaPeer before hearing the backstory about Roberts’ name change. Johnson also learned that Roberts had been the DJ on a funky soul music station that Johnson listened to in the 1980s.

As a sports broadcaster, Roberts was known for his energy and vivid descriptions with a style reminiscent of legendary Lakers broadcaster Chick Hearn.

“He wasn’t one of those guys who had to hit the 100-decibel level with everything that happened,” Johnson said of Roberts, “but he would build up to a climax of a play and his enthusiasm and excitement would increase depending on the situation. … He was so good at painting a picture to make you feel like you were at the game — he would bring you in and keep you in.”

Developing a natural chemistry as partners, Johnson rarely needed to use the signal he had devised to tap Roberts on the leg whenever he had something to add as the analyst.

“He wasn’t the type of play-by-play guy that wanted to suck up all the airtime,” Johnson said. “He would always look at me like, ‘Your turn,’ and it was almost a cadence we developed; he would describe the play and look at me and it was my time to get in with a succinct point.”

Going on to become an Emmy Award-winning television broadcaster for the Milwaukee Bucks, Johnson credited Roberts with more than being a supportive partner who taught him the importance of meticulous preparation during their several years together in the 1990s.

“Chris Roberts was just a real godsend for me where I was at that point in my career and things that were going on and challenges that I was going through,” Johnson said. “He was just really good at keeping me loose and keeping me laughing and we had such a great time together that it was almost like stealing money. It was so enjoyable that it was something that I would have done for free based on the moments and experiences we had together.”

Roberts is survived by his wife, Ann LaPeer; son David LaPeer and daughter-in-law Yvette LaPeer; daughter Nichole Hijon-LaPeer and son-in-law Octavio Hijon; and grandchildren Andres, Santiago and Carmen. Services are pending.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.