Martin Jarmond arrives at UCLA eager for his greatest challenge

He is the longshot that kept coming in, the walk-on who became team captain, the student with bad test scores who made his university proud, the grunt who fetched Chardonnay now running his own department.

There are bigger comeback stories than Martin Jarmond, if only because he’s been considered a bit undersized going back to his days as a scrappy point guard.

He has sprouted into one of the nation’s fastest-rising athletic directors, his unlikely journey that started in a drab North Carolina town having brought him to the glitz of UCLA only a few months after he turned 40.

“A lot of people say, ‘Can you believe it, from Fayetteville to Westwood?’ ” said Jerry Wainwright, Jarmond’s coach at North Carolina Wilmington. “Yeah, I absolutely believe it. I honestly thought at some point if it wasn’t athletics, he would be a relevant politician. He just had that way of bringing people together.”

On the hardwood he was the player everybody gravitated toward, the one who always had the answers, whether it was a teammate seeking assurance or a coach wanting to gauge practice fatigue.

Hey, M.J., are we tired now? What do you think? Should we keep going?

It didn’t matter that Jarmond wasn’t always the best player because he was always the best at knowing what to do and how to make it happen.

People followed him everywhere. One third-grade friend received permission from the school to ride the bus home with him to shoot baskets and hang out. In college he was known as the Mayor because it seemed as if everybody in town knew him.

His charisma gave him outsized value once he went into fundraising for college athletic departments. He could build relationships and the trust needed to raise vast amounts of money.

It was never as easy as Jarmond made it appear. He worked tirelessly, remembering his mother driving an hour to work each way and bringing in the week’s worth of groceries in one trip from the car no matter how many plastic bags she had to clutch in each hand.

Martin Jarmond, UCLA’s new athletic director, was 16 years old when he had a gun placed against his head after being pulled over for speeding.

The other day he went running and wanted to go four miles. About 1½ miles in, already dragging, he thought about walking the rest of the way. He pushed on, even as the thought came back again and again.

“I just said, you know what, I’m going to see this through,” Jarmond said. “I started this, I’m going to finish this, and I finished and I was so proud.”

A sense of resolve has carried him back to the starting line as perhaps the most improbable new athletic director in UCLA history and the first without any ties to the university. Sometimes even Jarmond has trouble believing his own story arc.

“I’ve been in situations and afforded opportunities that don’t make sense and I don’t understand,” Jarmond said, “so I feel like it’s a higher purpose and a higher calling for me.”

::

One of the first things Jarmond wants to get for his new office is a sign reading “334 Mallard Way.”

That was the address of the mobile home he lived in for roughly a year when he was 6, playing tackle football on a patch of grass with friends Chico and Peanut. They ended up in jail and Jarmond eventually lost touch, but he never wants to forget them or how his life might have taken a less fortunate path.

Jarmond was still stacking wooden blocks when he provided the first inkling that he might be unlike the others flitting about his kindergarten class.

The teacher told his mother there was no challenge she could put in front of the boy that he couldn’t conquer.

Putting in the work became an accepted part of daily life. Jarmond’s father, Matt, recalled seeing his son distraught in middle school and asking what was wrong. Martin told him that a classmate had accused him of cheating on a test, prompting his father to say it didn’t mean anything because Martin knew he didn’t cheat.

“It might not mean anything to you,” Martin shot back, “but it means something to me.”

The boy had learned there were no shortcuts watching his parents. Matt Jarmond was a human resources administrator who also made time to coach youth teams and call Fayetteville State basketball games as a radio color analyst. Virginia Jarmond rose through the ranks to become a senior-level administrator at the North Carolina office of the Social Security Administration.

There was no debating which parent Martin took after; it was the one who, if he was running late, everybody knew there was no reason to worry because he had just stopped to talk to somebody.

“He has his dad’s personality, 100%,” said Edward Johnson, Martin’s best friend since the third grade who often rode the school bus home with him. “He’s always the life of the room. We just clicked immediately because of the way he is with people — he’s always funny, hilarious and real smart at the same time.”

Players on the UCLA football team and other sports teams who live locally can return to campus, but will not be penalized if they choose to stay away.

Martin grew up as a three-sport athlete, splitting time as a quarterback, second baseman and point guard pushed in every endeavor by his brother, Trey, who was five years older. The Jarmond boys eventually gravitated toward basketball while playing alongside Jeff and Jason Capel, who would gain national acclaim while playing at Duke and North Carolina, respectively.

Martin became a celebrated player at Pine Forest High as part of a remarkable turnaround in which he went from being cut by his eighth-grade team to making the varsity two years later. But his lack of a reliable jumper, not to mention his standing just 5 feet 10, ruled him out as a major Division I college player.

Shrugging off the lack of interest, he pitched Wainwright on playing for North Carolina Wilmington, selling himself as a tenacious defender who could get the ball to teammates more gifted at scoring.

“He is as confident a young man as I’ve ever been around in my life,” said Wainwright, 73, who also coached eventual NBA superstar Tim Duncan when he was an assistant at Wake Forest, “and I’ve been around a lot of great players.”

Wainwright added Jarmond to his roster as a walk-on, and two years later put him on scholarship and named him a team captain. That also happened to be the first season the Seahawks made an appearance in the NCAA tournament, a momentous triumph even if they were blown out by second-seeded Cincinnati in the first round.

As a senior, Jarmond met with Wainwright to discuss his future. The coach mentioned that he thought Jarmond would make a natural fundraiser in college athletics because of his way with people, catching him by surprise.

“I really had never heard about fundraising,” Jarmond said, “and I wasn’t thinking about grad school.”

Wainwright helped him apply for the John McLendon minority postgraduate scholarship at Ohio University, which had one of the best athletic administration programs in the country. It would require more selling because of Jarmond’s terrible

Graduate Management Admission Test scores.

“I told them in my interview, ‘I know I have the lowest scores of everybody applying,’ ” Jarmond said, “ ‘but I guarantee you one day I will graduate from this program and you will be proud of me as an alum of Ohio University.’ ”

::

Getting into graduate school might have been the easy part.

It was a dual degree, meaning that Jarmond was working toward a master’s in business administration and sports administration. He would call Wainwright sometimes to vent about the workload and lack of a social life.

But the payoff was almost immediate, Jarmond landing a job in fundraising at Michigan State after his graduation in 2003. Some of the tasks were menial, Jarmond regularly bringing one of his bosses Kendall-Jackson Chardonnay at events. He quickly proved himself, rising from assistant director of development to director in a year while eventually helping to raise more than $126 million.

His fundraising prowess caught the attention of Gene Smith, the athletic director at Ohio State, a Big Ten Conference rival. Smith hired Jarmond as associate athletic director for development in 2009 and eventually promoted him to his deputy, allowing him to essentially run the department while Smith was away handling national responsibilities for the NCAA and Big Ten.

That meant Jarmond handled public speaking engagements and met with the university’s board of trustees, tasks he was ideally suited for because of his easygoing nature and approachability. He also helped the department set fundraising records three years in a row even as the country emerged from a recession.

“Everything in this business is about people, is about relationships,” Smith said, “and he’s exceptional at that.”

As an African American, Smith had encountered many of the same obstacles facing Jarmond, making him particularly invested in helping his protégé advance in his career. Sometimes that meant making him uncomfortable.

When Jarmond prepared to interview for the athletic director’s job at the University of Houston in 2015, Smith told him to make sure he got a haircut beforehand because his look wasn’t tight enough. The thing was, Jarmond had just gotten his hair cut earlier in the day and was intentionally wearing it a touch longer.

Jarmond walked out of his boss’s office furious. He was an individual who should be able to wear his hair however he wanted, he thought. Besides, he had just gotten it cut.

Later, after he heeded Smith’s advice and went back to his hairstylist, Jarmond realized the role of candid conversation in leadership.

“What I learned from that is, you have to be OK giving people feedback even when it’s something they may not want to hear because at the end of the day, that’s more important,” Jarmond said. “Take the emotion out if it’s something that needs to be said or expressed because of care for them.”

::

Jarmond didn’t get the Houston job but wasn’t discouraged.

Something momentous would come along soon enough.

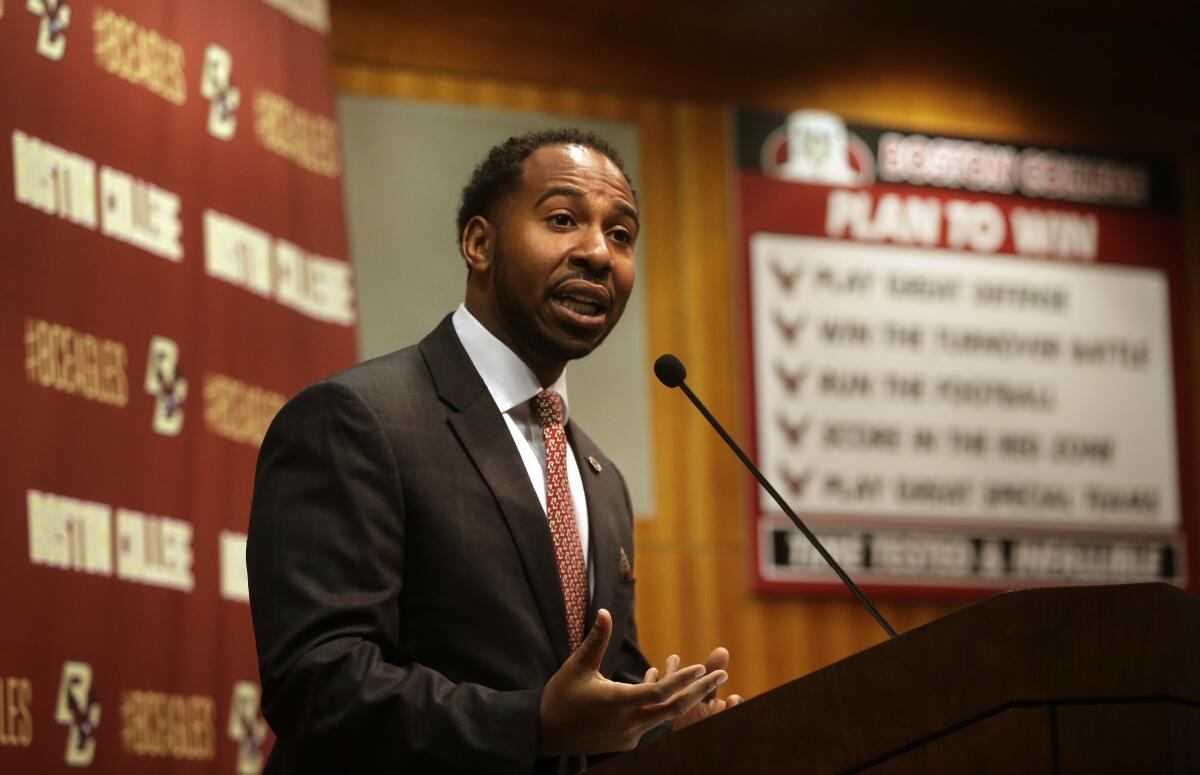

Boston College hired Jarmond in 2017, making the then-37-year-old the youngest athletic director in the Power Five conferences and the first African American to hold the post in school history.

In just three years, he revived a sleepy athletic department, bringing ESPN’s pregame football show, “College GameDay,” to campus and procuring more than $121 million as part of the largest fundraising campaign in Atlantic Coast Conference history.

He exhibited a personal touch, reaching out directly to fans on social media, lending his name to school-themed athletic apparel as part of the “Martin Jarmond Collection” and starting promotional videos with the same catchphrase: “We heard you.”

Jarmond showed he would not stand for mediocrity with the school’s flagship program when he fired football coach Steve Addazio despite winning records in five of seven seasons. Replacement Jeff Hafley quickly reinvigorated the fan base with his credentials as a former Ohio State co-defensive coordinator with NFL experience.

Hafley didn’t come cheap, providing Jarmond with a lengthy list of upgrades he wanted … and received, including a nutritionist, more strength coaches and analysts, and additional money for his assistants.

“Everything he told me during the interview process he followed through with and he fought for,” Hafley said of Jarmond, “and I’m forever grateful for everything he did.”

Their partnership ended when Jarmond took the UCLA job in May after an unusual courtship. He wowed the search committee via Zoom interviews necessitated by the COVID-19 pandemic, signing a six-year contract that will pay him an average annual salary of $1.4 million.

All this without having set foot on campus, something that Jarmond plans to do for the first time this week.

His imprint could be felt before his official June 15 start date, Jarmond creating a Voting Matters Initiative intended to help the school’s athletes enact meaningful changes in a time of social unrest. He also has unflinchingly engaged in a difficult conversation, alleviating the safety concerns of football players over their return to campus amid the ongoing pandemic that threatens the fall sports schedule.

Other issues await, including a massive budget shortfall and a football program that needs fixing after coach Chip Kelly, hired amid great fanfare, went 7-17 in his first two seasons.

As he contemplated whether to take the UCLA job or continue his work at Boston College, Jarmond called his parents to feel them out. His mother reminded him of his history of embracing bigger challenges and believing that he could solve any problem, no matter how seemingly insurmountable.

Jarmond ended the conversation feeling he was ready for the next step, even if it required a longer stride than he had ever taken.

“There’s some kind of purpose that I am meant to fulfill and I’m still figuring that out and that’s what drives me,” Jarmond said. “Who would have thought I’d be living in L.A. or working at UCLA? I never thought that, but there’s a reason for that, so you have to listen to that.”

Maybe it’s just the underdog in him, preparing for his latest coup.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.