To the family of UCLA’s John Wooden, ‘Papa’ will always resonate

He comes to them now, every day still, his presence felt in a moment, a memory, a smile.

Often it’s through a reminder of something he said. Maybe a story he shared. Something that seemed infinite in its wisdom.

The man himself was a gentle and reflective soul, once a basketball coach, always a teacher. His lessons of love and patience and understanding have endured, like a library book that remains in circulation despite frayed pages and a cover worn beyond recognition.

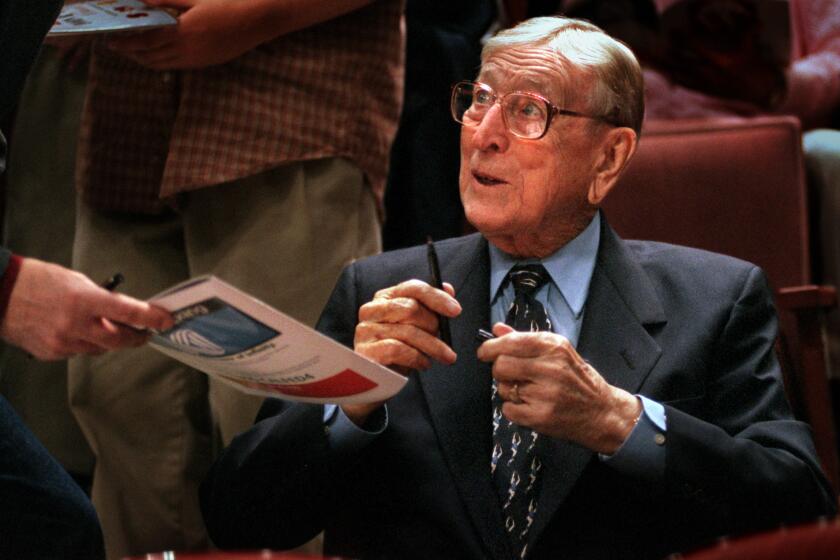

Ten years after John Wooden died, his memory lives on in everyone he touched. Players recall his devotion to winning at life, all those UCLA national championships in basketball in the 1960s and ‘70s a function of his dedication to doing things the right way. Those who met him or have read his books or have heard him speak continue to delight in the universal truths of what he said.

One group remembers him uniquely. He was their father, grandfather, great-grandfather. They all called him Papa.

“A lot of times when my friends are in need, my kids, I think, gosh, I wish Papa was here,” said Kim Robbins, 54, one of seven grandchildren and part of a Wooden family tree that also includes two children and 13 great-grandchildren.

The family remains based in Southern California some 45 years after Wooden coached his final game with the Bruins. Daughter Nan Muehlhausen, 86, resides in a San Fernando Valley care center after a series of strokes and son Jim Wooden, 83, lives in Irvine.

In past years, the family would often gather on the anniversary of Wooden’s death at VIP’s, the Tarzana café where he liked to order two eggs over easy, two pieces of brittle bacon, a toasted English muffin with butter and strawberry jelly and hot tea with a spoonful of honey. They would also visit his wall crypt at Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Hollywood Hills, where the coach lies in perpetuity next to beloved wife Nell.

No such formal remembrance is planned Thursday, even as VIP’s recently reopened for in-person dining, because of the COVID-19 pandemic that has largely confined people to their homes over the last three months.

That will leave the family to remember Wooden in their own ways on the 10th anniversary of his death at 99 on June 4, 2010, because of natural causes. All Jim has to do is glance across a den that doubles as a shrine to his father.

“As a matter of fact, I’m looking at his Purdue letterman’s sweater,” Jim said last week over the phone with a chuckle, referring to the memento John earned as a three-time All-American who led the Boilermakers to their only national championship, in 1932.

Jim doesn’t get out as much as he used to, walking with the help of a cane after undergoing a quadruple bypass about seven years ago. But he still eagerly hands out cards featuring some of his father’s core beliefs — never lie, never cheat, never steal and don’t whine, don’t complain, don’t make excuses.

John Wooden’s saint-like wholesomeness, which never produced a rebuke more profane than “Goodness gracious sakes alive,” may be the reason no feature film has ever been made about his extraordinary life.

A lot of times when my friends are in need, my kids, I think, gosh, I wish Papa was here

— Kim Robbins, one of seven grandchildren and part of a Wooden family tree

“Nobody wanted to do it because there wasn’t anything bad in it,” Jim said of a script that was shown to movie executives. “They wanted something bad to happen. Well, there isn’t anything bad. He never did anything bad; he never did anything wrong.”

Some might say the specter of Sam Gilbert could qualify as an element of evil. The rogue booster landed UCLA on probation for violations committed after Wooden’s retirement, though a Times investigation found that Gilbert’s indiscretions stretched to the coach’s heyday. Wooden acknowledged that “maybe I trusted too much” but said his conscience was clear.

The Wooden project has been revived, with interest in making it either as a feel-good movie or a television series similar to “The Last Dance” that chronicles different seasons and the racial hardships his players endured that were often forgotten amid the record 10 national titles they helped Wooden collect at UCLA.

“My grandfather was unreluctantly a big part of the civil rights movement with his black players,” said grandson John Todd Wooden, 55. “If they didn’t allow them to play, he’d put them back on the bus and he wasn’t doing that to make a political statement, he was doing that because they were no different than the other students and to deny them [the opportunity] to play wasn’t right.”

My grandfather was unreluctantly a big part of the Civil Rights Movement with his black players. If they didn’t allow them to play, he’d put them back on the bus and he wasn’t doing that to make a political statement, he was doing that because they were no different than the other students and to deny them [the opportunity] to play wasn’t right

— John Todd Wooden, grandson

A movie could provide the kind of financial windfall that the elder Wooden never enjoyed until his later years. Jim said his father made more money in his first two years after retirement as a speaker than he did in a lifetime of teaching and coaching. His final UCLA salary during the 1974-75 season was $32,500, which is about $161,000 in today’s dollars.

The Woodens mostly lived in a series of apartments during his 27 seasons at UCLA except for the handful of years they resided in a three-bedroom, two-bath house on Colby Ave. in West Los Angeles. Today, that modest home built in 1948 has an estimated value of $1.7 million.

It’s been 10 years since the death of UCLA basketball coach John Wooden and we still miss his simplicity and grace, writes columnist Bill Plaschke.

After Wooden retired, onetime Bruins star Mike Warren and UCLA alumnus Murray Neidorf were among a group of admirers who tried to pay the coach back for all he had given the school. Their offer to buy Wooden a home was quickly rebuffed, the coach saying he intended to die in the Encino condominium where he had lived with Nell before her death in 1985. Then they offered to buy Wooden a new car.

“He goes, ‘Well, what’s wrong with my ’98 Ford Taurus?’ ” Jim Wooden said with a laugh.

Finally, Wooden acknowledged there was something he would like: a scholarship fund for his great-grandchildren. James A. Collins, a restaurant and food service tycoon who graduated from UCLA, agreed to become the largest of many donors. Among the many beneficiaries, Avery Wooden, Jim’s granddaughter, will start Auburn in the fall with roughly $250,000 in her tuition fund.

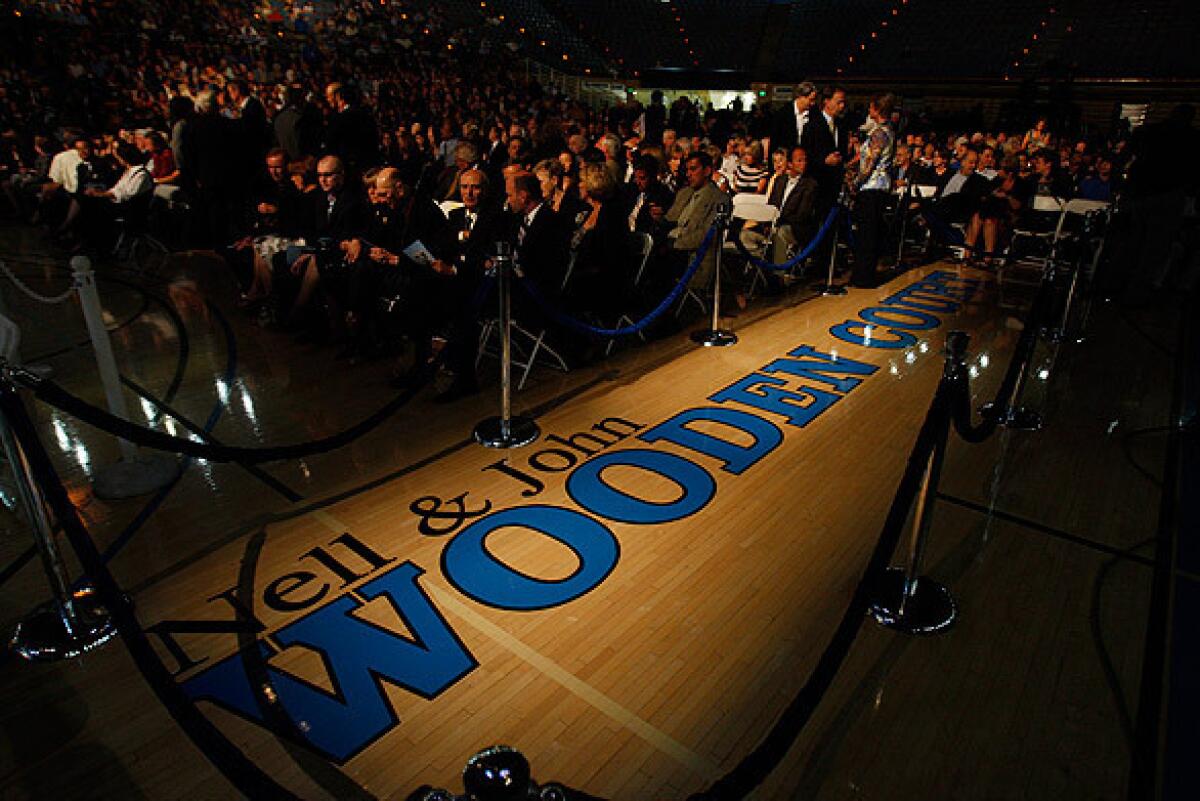

One of the family’s favorite gathering spots remains Pauley Pavilion, where the court is named after John and Nell Wooden and a statue of the coach stands outside one entrance. Both sides of the family retain a pocket of seats together in the same section behind the Bruins bench, where they always greet one another before games.

The court holds special meaning for the one family member who played on it. Great-grandson Tyler Trapani turned a teammate’s airballed shot into an alley-oop layup in the final seconds of UCLA’s victory over Arizona in February 2011, scoring the last basket in the final game before Pauley Pavilion underwent extensive renovations.

They were the only points of an otherwise unremarkable career, a cherished farewell to the court where his great-grandfather won 149 of 151 games.

“Every time I look at it,” Trapani said of the replay, “it still gives me goosebumps because I think it was him who put me into that perspective of where I needed to be.”

Trapani, 30, has turned one area of his Simi Valley home into what he calls his “Papa room,” a memorial to its namesake complete with pictures, trophies and books of Wooden. Trapani has also honored his forebearer by becoming a teacher in math and history at St. Nicholas School in Northridge, posting a Pyramid of Success in his classroom and repeating the Wooden mantra before tests that “failing to prepare is preparing to fail.”

Some reminders of the coach are reflexive. John Wooden’s namesake grandson often gets stopped for chats about the coach whenever people hear his name. Greg Wooden, 57, thinks about his grandfather every time he puts on his socks and shoes, having long ago attended the coach’s summer basketball camp when he first heard him launch into his famous spiel.

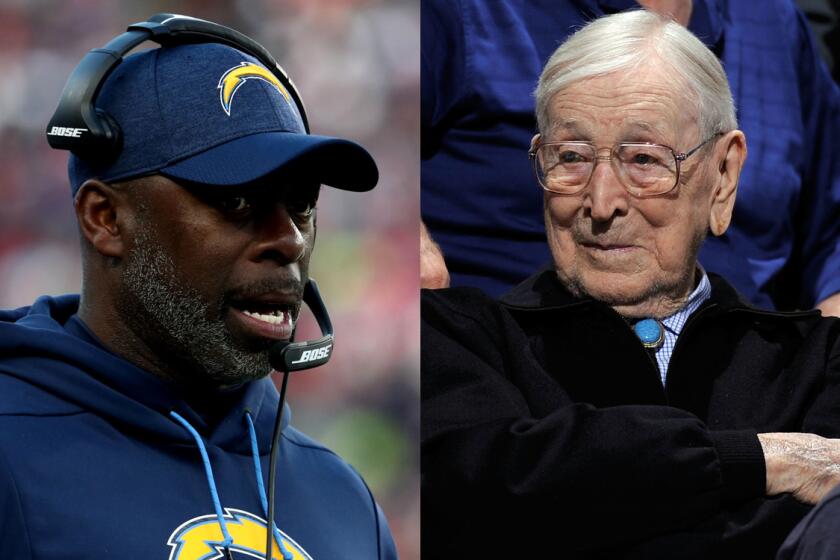

Chargers coach Anthony Lynn was an assistant for the Broncos when he had lunch with John Wooden in 2000. What the legendary UCLA coach said has stuck with Lynn to this day.

“He would go into detail about how, you know, if you have a little crease in there, you’re going to get blisters and if you get blisters you’re not going to be able to play,” Greg Wooden said, “so I always want my players to be able to play, I always want them to take care of their feet.”

Caring for others was a lifetime theme that makes Kim Robbins ponder how her grandfather would have handled the dual crises sparked by the novel coronavirus and racial unrest in the wake of another instance of police brutality against African Americans.

“Love is the most important word in the English language, followed by balance,” Robbins said, repeating one of Wooden’s teachings. “And I think love is something that our world needs right now. The world would be a better place if people would love one another.”

Robbins sought her grandfather’s wisdom recently when she was asked to speak at a friend’s wedding that was held much earlier than expected. She thought about what her grandfather had said when she got married, to always keep her husband in mind, and delivered a message about open communication and mutual understanding.

It was Papa emerging once more, his timeless presence providing another gentle caress.

VIP’s Cafe in Tarzana, where John Wooden had breakfast each morning, nearly had to go out of business because of the COVID-19 pandemic. The owners are hoping to bounce back.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.