Missouri protests echo similar situation at UCLA in 1998, but with a bad outcome for football team

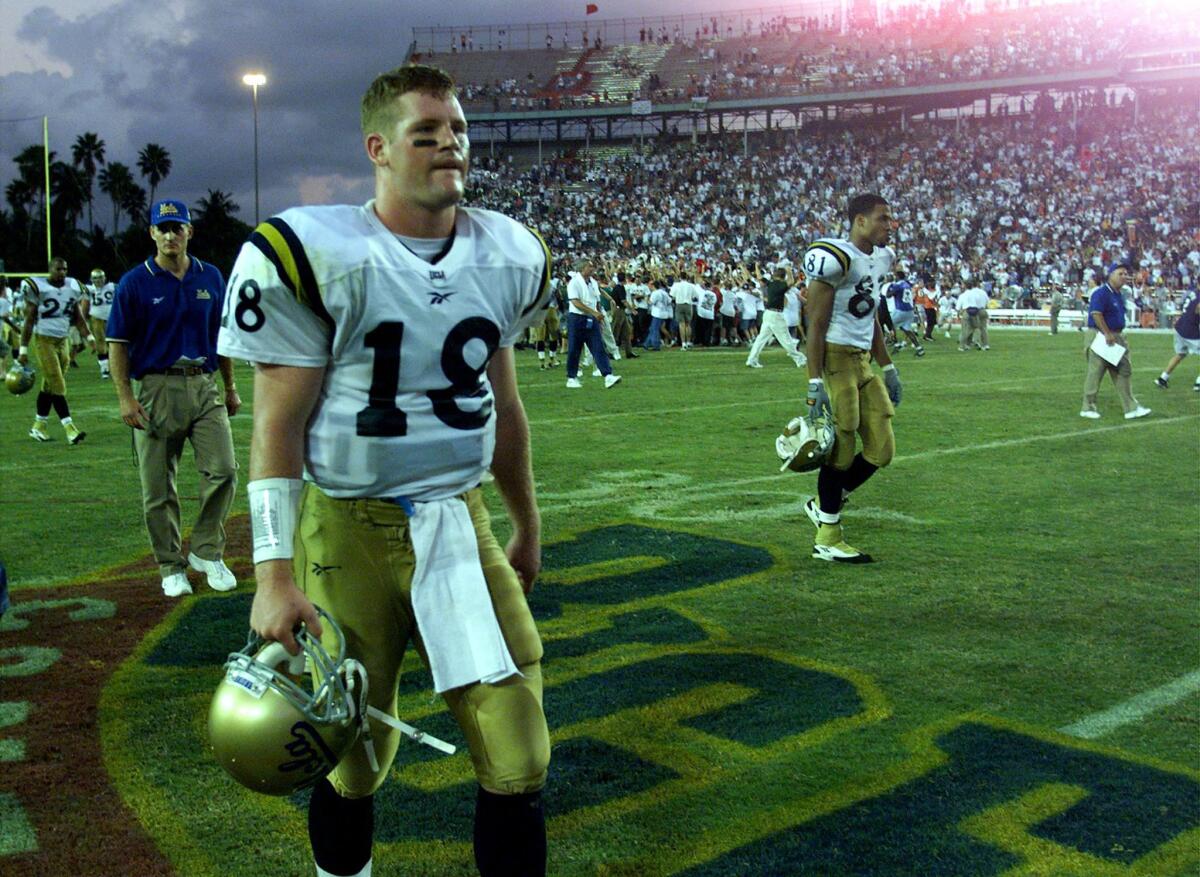

UCLA quarterback Cade McNown walks off the field after a 49–45 loss to Miami at the Orange Bowl in 1998.

A group of seemingly powerless college athletes have realized their immense strength. A group of unpaid workers have exercised their control over great riches.

The voice of the college athlete has finally been heard, and its words have toppled a king.

Tim Wolfe, University of Missouri system president, resigned Monday after being swamped by protests that he was enabling racial tensions. The demonstrations came from all corners of campus, and even included a hunger strike by graduate student Jonathan Butler, but make no mistake about the biggest push here.

Wolfe never leaves his office if he’s not thrown into the street by some 30 black members of the Missouri football team, who last weekend announced they would not participate in any team activities until he was gone. The Tigers have won only four of their nine games, but this was a championship move endorsed by character Coach Gary Pinkel, their gang tackle galvanizing the movement until the school’s highest-ranking official disappeared.

The football boycott brought national attention to the situation that no other protest could have garnered. The football boycott also threatened to hit the university where it would hurt the most — in its wallet — as the school would have lost more than $1 million if the Tigers did not show up for Saturday’s game against Brigham Young at Kansas City’s Arrowhead Stadium.

And so college athletics’ silent majority finally showed the mountains that can move when its voice is heard, and that’s a good thing.

All too well, longtime UCLA football fans know the eternal nightmare that can be created when that voice is squelched.

I was there. I saw it. I was close enough to touch it, close enough to be disgusted by it, and anybody standing near me on that Orange Bowl sideline in Miami would surely agree.

It was Dec. 5, 1998, and the unbeaten UCLA football team needed only to defeat inconsistent Miami to extend its 20-game win streak and advance to the first Bowl Championship Series title game.

The game, originally scheduled in September but postponed because of Hurricane Georges, should have been a lock for UCLA. But where many of today’s Missouri players bonded together over a social issue, those long-ago Bruins were torn apart.

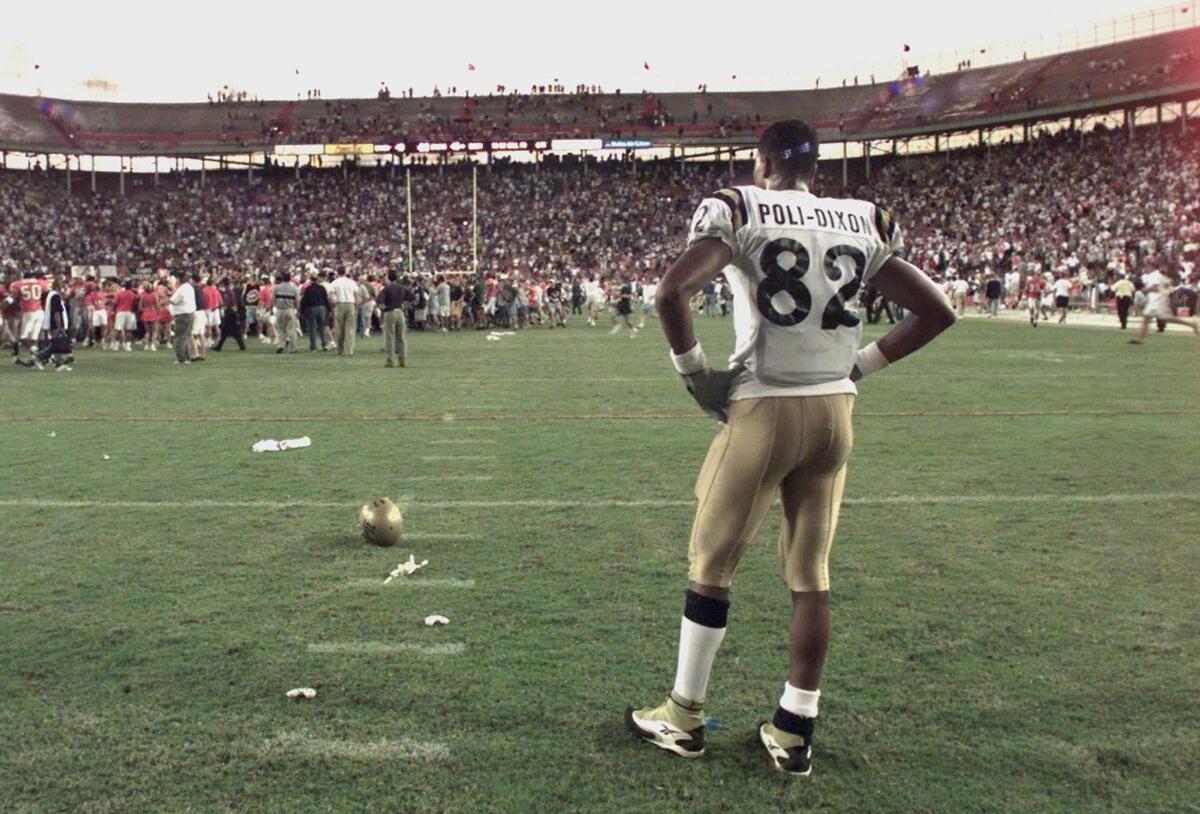

UCLA’s Brian Poli–Dixon is dejected as he watches Miami celebrate on the field at the Orange Bowl on Dec. 5, 1998.

Over wristbands.

The week before the game, some UCLA players petitioned to wear black wristbands in support of a university-wide protest against Proposition 209, a state constitutional amendment that prohibited affirmative action in state programs and university admissions. Approved by voters in November 1996, the measure was challenged in the courts but ultimately would be ruled constitutional by the California Supreme Court in 2000.

Bob Toledo, the Bruins’ coach, opposed the wristbands in keeping with his stance that athletics shouldn’t be used to make a political statement. The team followed his lead and voted against wearing the wristbands.

But enough players believed strongly enough in the cause that the entire night before the game was lost to debate and distraction.

“It was the worst Friday meeting we’ve ever had,” Toledo told me several years ago. “I had to just send them off to their rooms — we couldn’t get into small groups — there was so much talking back and forth about it. It was a huge distraction.”

Toledo has long refused to comment on the theory that the wristband issue led to the Bruins’ demise. But to those who witnessed it, there was no question.

The UCLA defense, filled with players who supported the wristband movement, played as poorly as any defense in UCLA history in a 49-45 loss.

Miami racked up 689 yards in total offense, the most allowed by a UCLA team in nearly 70 years. Edgerrin James, Miami’s emerging running back, set a UCLA opponent record with 299 yards rushing.

The defense missed so many tackles that Toledo later showed his team film clips of each blatant failure before finally stopping at 10.

The defense missed so many coverages, UCLA guard Andy Meyers said at the time, “There were so many guys open . . . we were lucky they didn’t score 60.”

That’s right, it was such a complete humiliation of the Bruins defense that the Bruins offense openly ripped teammates, with Meyers adding, “I was ready to go play on the d-line. It was really a feeling of disgust.”

Miami scored on one play when there were only 10 UCLA defenders on the field. Miami scored another time on an 80-yard drive consisting of four runs requiring 70 seconds. Miami was down 38-21 in the second half before rolling basically untouched to the victory.

Folks will remember that the game officially turned on an horrendously bad call —- with 3:24 left and the Bruins heading for a potential clinching score, receiver Brad Melsby was ruled to have lost a fumble even though his knee was clearly down before he dropped the ball.

But the bigger picture was about the poor play of a defense with players whose social consciences had been squelched and their voices silenced, a defense whose effort led to an unprecedented open apology to the entire university — even to then-chancellor Albert Carnesale — from defensive coordinator Nick Aliotti.

“It was, by far, the most horrendous performance by a defensive football team that I think I’ve not only been involved with, but watched on TV,” Aliotti said at the time. ‘“There was so much riding on this game today, it’s hard to fathom how we could have played so poorly.”

When asked about his play afterward, cornerback Marques Anderson said, “Hmmm . . . well . . . hmmm.”

Cornerback Jason Bell added, “The defense knew that we did things that didn’t help win the game. We knew that and our teammates knew that.”

Eventually, center Shawn Stuart attempted to calm the speculation, saying, “That whole armband thing . . . I think people made a bigger deal of it than it was. I think guys were shocked how big a deal it was made out to be, compared to what it really was. It was ridiculous.”

The devastating loss became two devastating losses when UCLA still was unsettled during a 38-31 Rose Bowl defeat to underdog Wisconsin. It was the beginning of the end of the briefly spectacular Toledo era. His team would go just 24-22 in the next four years before he was fired, and the Bruins haven’t been that close to a national title game since.

“I’m sick,” Toledo told his players after that Miami loss. “I’m just sick.”

While folks in Missouri celebrate today, those in Westwood will look back with that same sick feeling of a protest halted, a voice silenced, and maybe even a championship lost.

Twitter: @billplaschke

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.