Chi Chi Rodriguez, Hall of Fame golfer known for antics on the greens, dies at 88

He was an unlikely superstar when he emerged on the PGA Tour in 1960. A 5-foot-7, 117-pound rail of a man who had grown up in extreme poverty in Puerto Rico, he was far removed from the blue-blood, country-club set that populated the tournament scene.

Most of the players he competed against had grown up with top-of-the-line equipment and extensive coaching. He was a mostly self-taught golfer who had fashioned a swing using a branch from a guava tree for a club and a crushed tin can for a ball.

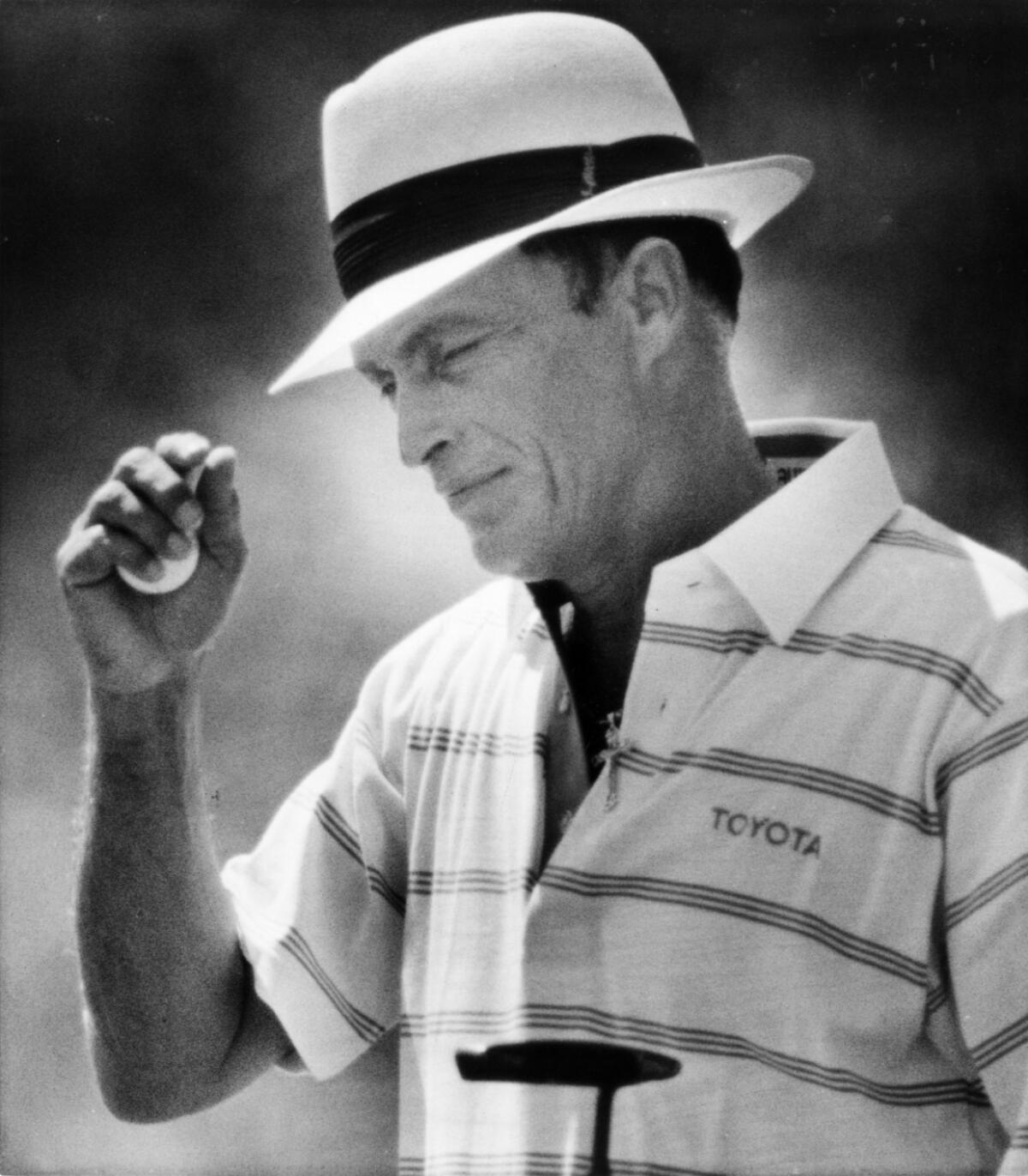

But Juan “Chi Chi” Rodriguez quickly showed the world of professional golf that he could do two things at least as well as anyone: With a roundhouse swing that seemed to strain every muscle on his slight frame, he could drive the ball alongside and even beyond the longest hitters of his day, including Jack Nicklaus; and with a wit and flair for showmanship that was nonexistent on tour at the time, he became an immediate fan favorite and one of the most popular sports figures of his day.

He had only moderate success on the PGA Tour, winning eight times in just more than 25 seasons, but he won 22 tournaments in a record-setting senior career. Those accomplishments were only part of the reason he was inducted into the World Golf Hall of Fame in 1992. His lifelong dedication to helping underprivileged and at-risk children was at least as responsible for his enshrinement and for the many humanitarian awards he received.

Rodriguez died Thursday at age 88, according to Carmelo Javier Ríos — a senator in Rodriguez’s native Puerto Rico. He didn’t provide a cause of death.

Billy Bean, who played parts of six seasons with the Tigers, Dodgers and Padres, died Tuesday after a yearlong battle with Acute Myeloid Leukemia.

“Chi Chi Rodriguez’s passion for charity and outreach was surpassed only by his incredible talent with a golf club in his hand,” PGA Tour Commissioner Jay Monahan said in a statement. “A vibrant, colorful personality both on and off the golf course, he will be missed dearly by the PGA Tour and those whose lives he touched in his mission to give back. The PGA Tour sends its deepest condolences to the entire Rodriguez family during this difficult time.”

To those familiar with golf, Rodriguez was best known for his theatrics on the course and his willingness to entertain and interact with fans. His trademark became the “toreador” dance he regularly performed after making clutch putts. Flashing his club as a sword, he targeted the hole as the bull and completed the routine by wiping the imagined blood off the blade and returning it to an invisible scabbard with a flourish. Fans never tired of the routine.

“Golf is kind of a stuck-up sport,” Rodriguez told the Saturday Evening Post in 1989. “Therefore it’s tough to be a golf fan because [a fan] can’t speak, he can’t even cough when a guy is hitting a shot. … But I’m going to make sure that I do something to make them laugh or make them enjoy themselves. What is life without a laugh?”

Some players felt differently.

“I’m one of the ones he bothers,” tour player Johnny Pott told Sports Illustrated in 1964. “I’d just rather not be paired with him.”

Said Dave Marr: “I’ve got tremendous respect for him…. Chi Chi really came up the hard way. Still, I don’t approve of his actions.”

The criticism stung Rodriguez.

“It makes me sad,” he told Sports Illustrated in his fourth season on tour. “It makes me want to hide in my room and watch television and do nothing but sleep and go home…. I’ve never tried to bother anybody.”

At the 1964 Masters, Rodriguez took criticism from Arnold Palmer to heart. At that point in his career, Rodriguez’s routine after sinking an important putt was to throw his short-brimmed straw Panama hat over the hole and do a one-man tango around the green. Palmer, whom Rodriguez deeply admired, told him he needed to tone down the act, that it was distracting to many players, including Palmer.

So Rodriguez began holding off on his antics until other players had putted out. And he began to develop the toreador routine to replace the hat-over-the-hole trick after some players complained he might be damaging the cup or leaving spike marks on the green with his dancing.

But he never gave up performing.

“I never wanted to be like everybody else,” he told Golf Digest in 2000. “That’s what I tell kids to be. I tell them to be different.”

Rodriguez’s respect for and friendship with fellow pros ultimately made him a favorite of touring pros as well as the fans. He made a habit of offering tips to young players. In 1985, Rodriguez saw that Jack Nicklaus’ son, Jackie, was struggling with his chipping game and skipped his own practice time before the final round of a tournament to work with the young pro. Jack Nicklaus was also having problems with his chipping and incorporated Rodriguez’s technique in the 1986 season.

“By the time of the Masters I had switched fully to Chi Chi/Jackie’s method for routine chips and short pitches,” Nicklaus wrote in his autobiography, “My Story.” “It would not let me down.”

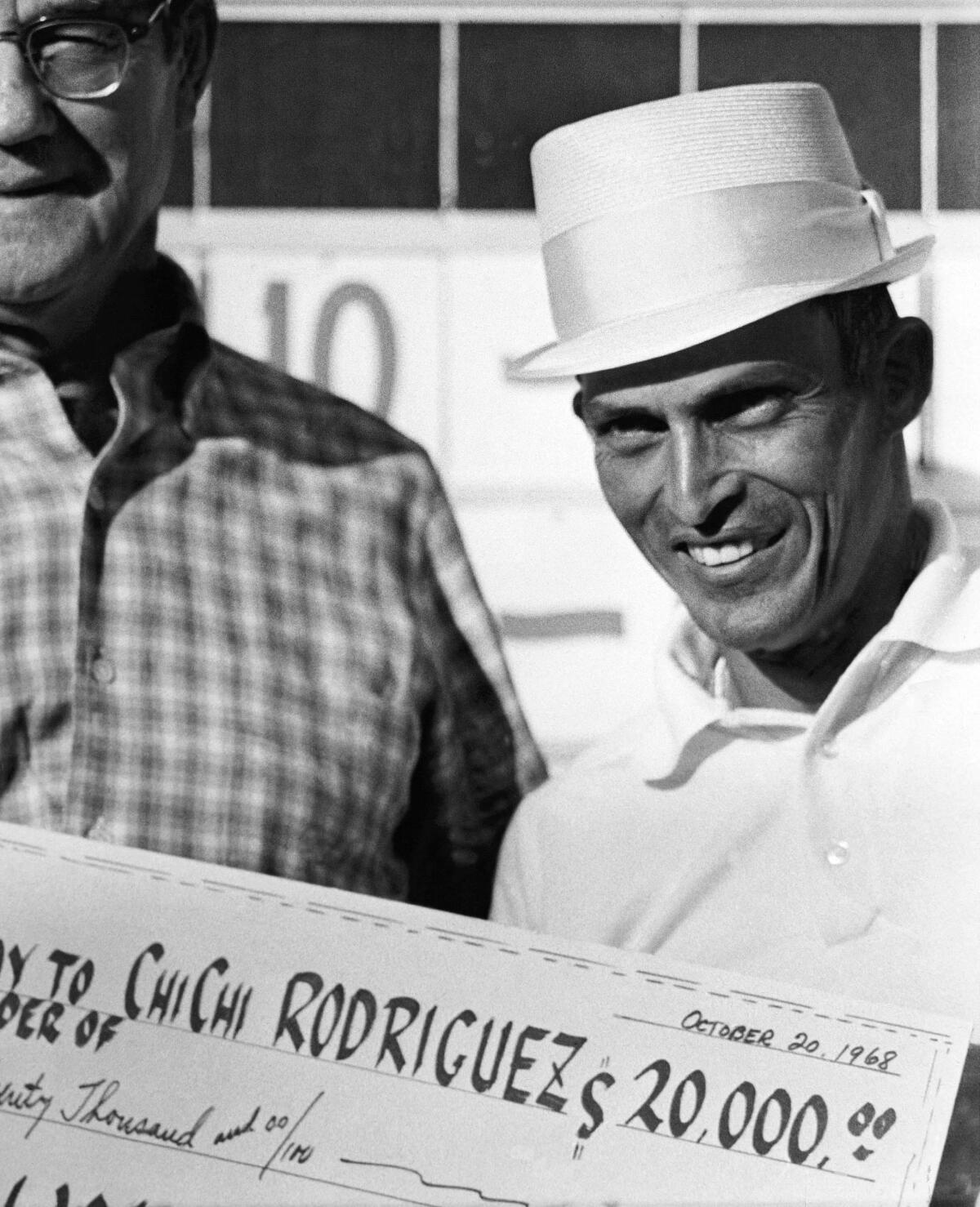

Chi Chi Rodriguez has made $4,809,895 in his golf career. Which, on balance, is a good thing.

Nicklaus, at 46, won the Masters that year, the last of his 18 major titles.

Rodriguez was paired with Ben Hogan several times early in his career after Hogan had survived a near-fatal car accident and resumed his career despite significant pain.

“I did my thing, just very carefully,” when playing with Hogan, he told Golf Digest. “First time I played with him, I said, ‘Look, Mr. Hogan, I know you have a bad leg. Mind if I fix your ball marks?’

“He liked that. ‘Yeah, you can fix my ball marks. I really appreciate that. Funny, you’re the first guy who ever said that.’”

Longtime pro Peter Jacobsen told Sports Illustrated in 1987: “Nobody is a nobody with Chi Chi. He shows young guys new shots, and he shows them respect. A lot of guys act according to what they shot, but Chi Chi has never been like that.”

Juan Antonio Rodriguez was born in Rio Piedras, Puerto Rico, on Oct. 23, 1935. The fifth of six children, he contracted rickets and tropical sprue, an intestinal disorder, at 4, both caused by vitamin deficiencies from his limited diet, and suffered from brittle bones throughout his life.

His father, Juan Sr., worked in the sugarcane fields, never earning more than $18 a week, and raised the six children alone after he and his wife separated when Chi Chi was 7. The younger Rodriguez began delivering water to field workers when he was 6, earning 10 cents a day, and by the next year was making a dollar a day working in the fields behind an ox-drawn plow.

But when he one day saw boys caddying for players at a nearby golf course, he decided to get out of the fields to try that line of work. He was a caddie by the time he was 8 and became intrigued by the game. He played against other caddies the one day a week they were allowed on the course to play and was intensely competitive.

Blessed with extraordinary hand-eye coordination, Rodriguez developed into an accomplished baseball pitcher as well, one who also could smack a pitched bottle cap with a broomstick. He adopted the nickname Chi Chi after Chi Chi Flores, a standout in the Puerto Rican winter league. But he realized that a player who was no bigger than a batboy wouldn’t have much of a career.

He dropped out of school in 11th grade and enlisted in the Army at 19 to help support the family. After two years in the service, he returned to Puerto Rico and eventually became caddie master at the new Dorado Beach resort. By 1960, thanks to a check for $12,000 from a part owner of the resort, Rodriguez had the seed money to try to make a go on the PGA Tour.

He finished ninth in his first event, the Buick Open, and earned $450.

“I never had to borrow money again,” he said.

His first tour victory came at the 1963 Denver Open, his eighth at the Tallahassee Open in 1979. Rodriguez’s best finish in a major championship was a tie for sixth in the 1981 U.S. Open, though he did win the 1964 Western Open, considered a major by many players until the early ‘60s. But his real success came after joining PGA Senior Tour. He won twice in 1986, his first full season, then in 1987 won seven events, including an unprecedented four in a row, and set a single-round record with eight consecutive birdies. He was the first player on that tour to win more than half a million dollars in a season.

A heart attack in October 1998 sidelined him for four months, but he completed full seasons on what would become known as the PGA Tour Champions from 1986 through 2002.

“That was great for my ego,” he told Golf Digest in 1999, “because guys like Arnie and [Gary] Player were always kicking my butt on the regular tour. I finally had the last laugh. I was kicking them back.”

Rodriguez was a conservative politically; he twice spoke for Sen. Bob Dole during his run for the presidency in 1996. But his love for Puerto Rico overrode any political affiliation shortly after the island was devastated by Hurricane Maria in 2017 and aid from the U.S. government was sporadic.

“We’re good Americans,” he said. “And we deserve better than we’re getting. There’s nothing happening. I hope Mr. Trump understands that.”

In 1979, the year of his final PGA Tour win, Rodriguez co-founded the Chi Chi Rodriguez Youth Foundation in Clearwater, Fla., to help at-risk and under-performing students. In partnership with the Pinellas County School System, the foundation soon began helping hundreds of fourth-through-eighth graders a year. The foundation also includes the Chi Chi Rodriguez Academy and its 12-hole public golf course.

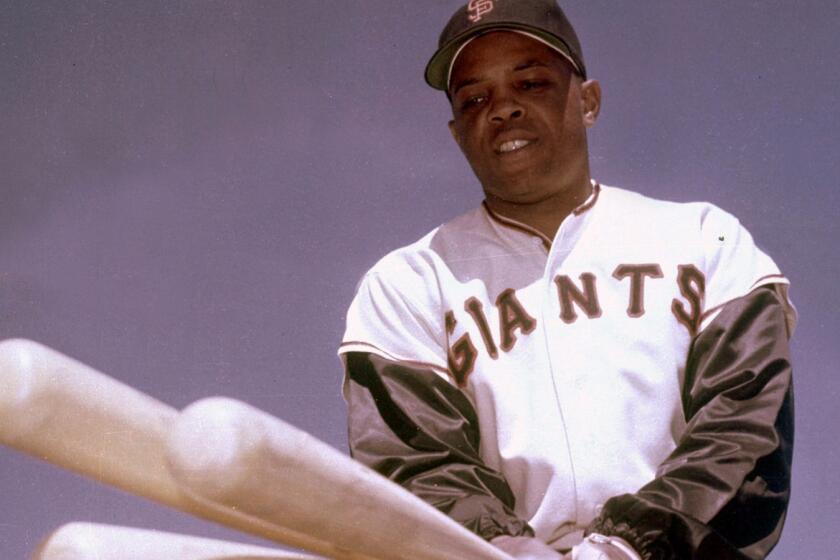

Willie Mays, widely regarded as the finest player in Major League Baseball history, died Tuesday afternoon, the San Francisco Giants announced.

Rodriguez was a frequent visitor to the academy during and after his playing days, his commitment to helping those in need a product of his father’s example in Chi Chi’s younger days. The image of his father, who died in 1963, giving away his dinner to hungry children he didn’t even know had a lasting impact.

“I like to give to kids,” he told the Los Angeles Times in 1993. “I figure adults have had their chances…. Kids are just victims.”

Among his many awards were the 1989 Bob Jones Award, the highest honor given by the United States Golf Assn., and his election to the World Humanitarian Sports Hall of Fame in 1994.

A phrase he often uttered described his affinity for helping youngsters in need: “A man never stands taller than when he stoops to help a child.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.