Commentary: Even after 25 years, Indian Wells continues to live up to its tennis paradise hype

When they start hitting tennis balls in the desert for real Wednesday, it will be a stunning 25 years since this has been going on at this place, a site and event where the term “Tennis Paradise” has become not only a marketing label, but a reality.

Now they call it the BNP Paribas Open, which means it is nicely sponsored and well established on the sport’s tours, both for men and women. In its two-week run, with all the best-known and most-famous players competing, surrounded by palm trees and nearby mountains, more than 450,000 people will walk through the gates, coming, seeing and hoping to be conquered by one of the greatest shows in sports.

One of these years, with the right players matching up at the right time, they may get half a million fans through the hallowed gates of the Indian Wells Tennis Garden. For perspective, at least one of the sport’s majors, the French Open, struggles annually to get more spectators than Indian Wells. When reporters call Paris and ask about that, the phone often goes dead. Ah, that international phone service thing.

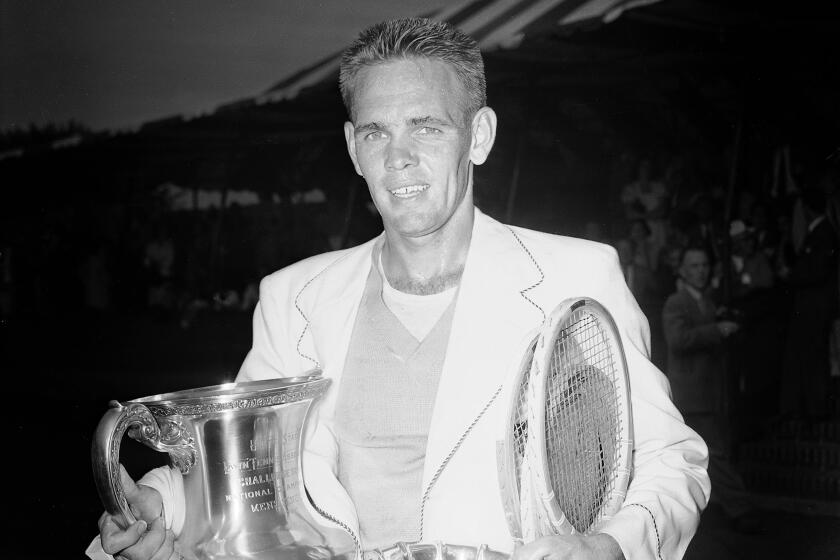

Seventy-five years ago, Jack Kramer won his first and only Wimbledon title, using it as a springboard to a pro-career template many players would follow.

For perspective, it should be noted that the nearest major metro, Los Angeles, is 100 miles from Indian Wells. To go watch tennis in Paris, you merely need to find a taxi. To go watch tennis at Indian Wells, you may have to find a travel agent.

This all started in 1974 in Tucson, Ariz., with John Newcombe beating Arthur Ashe in the final. The tournament wasn’t even an official tour stop then, even though its finalists were among the best in the world. That certainly hasn’t changed over the years. In the current edition of this event, both Roger Federer and Novak Djokovic have won five times and Rafael Nadal has won three titles in singles and two in doubles. The women’s tour came on board in 1989 and since then, the singles competition has been won twice by Martina Navratilova, Steffi Graf, Mary Jo Fernandez, Lindsay Davenport, Serena Williams, Kim Clijsters and Victoria Azarenka.

Big names and lofty expectations always come with this tournament. But the loftiest expectations, from the start, came from former world-class players Charlie Pasarell and Raymond Moore. Eventually, they were joined by a world-class thinker and doer, Steve Simon.

Pasarell and Moore, who had homes in the desert, got control of the event and brought it to Mission Hills in Rancho Mirage in 1976, where it went along nicely until the great desert flood of 1980. That year the tournament, still men only, ended after the quarterfinals as rain kept coming down and there were reports of Noah preparing his ark. That, and some business connections, prompted Pasarell and Moore to take it to La Quinta in 1981, where bleachers held 7,500 and still attracted the likes of Jimmy Connors and Yannick Noah.

It was a nice event. The great players still came, despite the cozy confines. But Pasarell and Moore didn’t think it was that nice. So, they put together some tennis-minded investors, built a place they called the Hyatt Grand Champions, with its corresponding hotel and more seating. The stadium, mostly temporary bleachers, rose up right along Highway 111, the main artery going through Palm Springs and the Coachella Valley. Talk about prime property.

Boris Becker won there when he was 19 years old. Pete Sampras beat Andre Agassi in one of those matches for the ages in the ’95 final. By ’96, the women’s tour had joined the event. Already, the worldwide tennis community was wowed by this desert event. There were only two naysayers — Pasarell and Moore.

“The Hyatt venue wasn’t big enough,” Pasarell said. “We didn’t have enough room.”

So, with most others rolling their eyes at that, the Desert Dreamers set off in search of more money and more community commitment and one day, there it was, rising out of the sand and desert dunes like an Egyptian pyramid. It seats 16,100. That makes it the second-biggest tennis-only stadium in the U.S., after the 23,771-seat monstrosity that houses the U.S. Open in New York, and the third biggest in the world, 1,400 seats fewer than O2 Arena in London. At the U.S. Open, with 20-20 vision and a telescope, you can see the action on the court. Without, you eat your hot dog and watch the big screen.

From that 1974 start in Tucson until now, the desert tournament has been called the American Airlines Tennis Games, the Congoleum Classic, the Grand Marnier¸ the Pilot Pen Classic, the Newsweek Champions Cup and the Pacific Life Open. In 2000-01, it was called the Tennis Masters Series at Indian Wells. That might just as well have been called the Pasarell-Moore Tennis Tournament, because there was no sponsorship and they were scrambling. Buyers from Shanghai were hovering and even an infusion of investment money from Tennis Magazine, Chris Evert, Billie Jean King and Sampras couldn’t hold off the banks forever.

Along came BNP Paribas, life was better and money was less of an issue. Not that there weren’t other issues.

Jake Knapp, former bouncer and UCLA golfer, won the Mexico Open, about $1.5 million and a trip to the Masters. He dedicated the win to his late grandfather.

In 2001, when Pasarell and Moore still were counting pennies, Serena and Venus Williams made their way to the semifinals against each other. Five minutes before the match was to start, Venus announced she was defaulting to Serena because she had an injury. In the final, when Serena played Clijsters, several fans booed Serena and it went on, uncomfortably, for much of the match. Serena won and a week later a story from USA Today quoted the sisters’ father, Richard, as saying there had been racist comments in addition to the booing. Other opinions held that the crowd anger had sprung from the Williams sisters making expensive semifinal tickets useless.

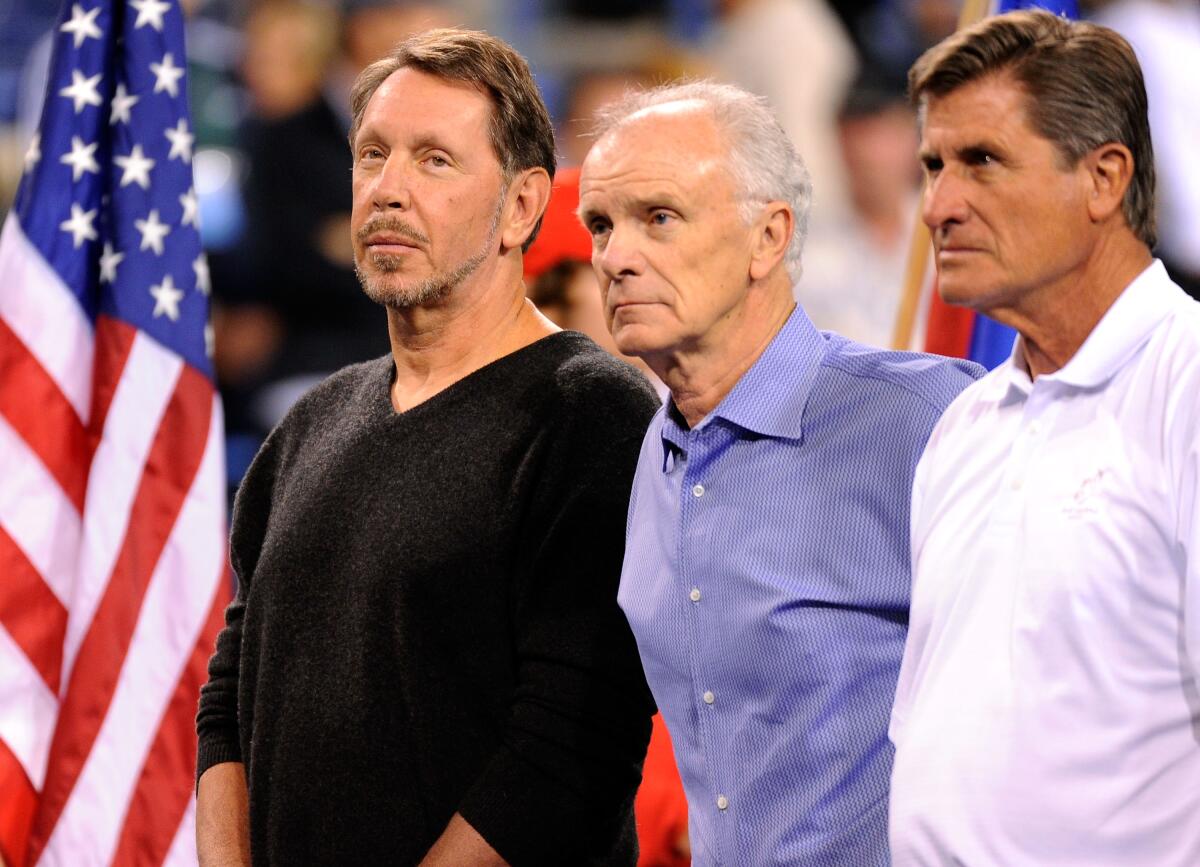

Serena and Venus refused to play the event for years, Serena returning in 2014 and Venus in 2016. During that period of time, one of the people most tasked with getting the Williams sisters to return was Simon, the tournament director. He never could get it done, but they did return, reportedly under the nudging of Oracle billionaire Larry Ellison, who bought the tournament in 2009.

Interestingly, when the women’s tour sought a new commissioner in 2015, it hired Simon. A year later he was forced to react to a statement by Moore that the women’s tour owed a great debt to the men and players such as Federer and Nadal for building the sport to the point where the women benefited.

“They ought to get down on their knees and thank them,” Moore said, distastefully. Simon, not at Indian Wells at the time but having been in the same news conference for years with Moore and Pasarell, had to respond, fully knowing the background of the battles the tournament had with the women’s tour for years. Simon may not have even disagreed, but Moore just said it so badly. Moore resigned from the executive position he held at the tournament and never really left his desk, taking on a new title. It was Moore, after all, who made most of the contacts and sales pitches to Ellison that led to the billionaire’s purchase.

One interesting tidbit, maybe you could call it irony. Or maybe simply all is forgiven. One of the wild cards handed out by the tournament this year went to Venus Williams, who will be 44 in June and is ranked No. 474.

Through it all, year by year, Indian Wells became a tennis Valhalla.

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Soon, the fans will flock back, for the 25th time at this venue. The palm trees will sway gently and the mountains will glimmer in the distance. Nadal will work on his golf handicap at the Ellison-owned Sensei Porcupine Creek. Navratilova, Fernandez, Davenport and probably Evert will be around to handle much of the broadcasting. Moore will stay clear of the limelight, Pasarell will come and greet old friends in box seats and around the grounds, being his magnanimous self, and Simon will slip in for a few days, see the people he has known for years, admire the event that his detail-driven mind took to new levels every year, and then slip out quietly.

Fans will buy inexpensive ground passes early in the week and shuffle from one outside court to another. Those will be the real hardcore tennis fans. Some will spend much of their time watching players warm up on the practice courts, where access to seating allows much more up-close-and-personal viewing than most tennis events. Others will cap the day with a dinner reservation in the fancy Nobu restaurant overlooking the court in Stadium 2.

Many others will wait for the sun to go down and settle into a comfortable chair alongside the big screen on the outside of the main court. You miss no action sitting there. Night tennis in the desert is, with an occasional weather curveball, appealing.

Several will even doze off, napping in Tennis Paradise, which is the only place that actually lives up to that hype.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.