Viva Las Vegas: MLB owners unanimously approve A’s move from Oakland

ARLINGTON, Texas — In 1901, when the American League was founded, the Philadelphia Athletics were one of the eight charter franchises. The A’s moved to Kansas City in 1955 and to Oakland in 1968, and they are on the move again.

No major league team has called four cities home, but the A’s are about to write a new and bittersweet page in baseball’s history book. Major league owners voted unanimously Thursday morning to approve the A’s move to Las Vegas, meaning a city that celebrated four World Series championships and nurtured Hall of Famers Reggie Jackson, Rickey Henderson, Catfish Hunter, Rollie Fingers and Dennis Eckersley soon will find itself without a baseball team to call its own.

“Today is an incredibly difficult day for Oakland A’s fans,” A’s owner John Fisher said. “It’s a great day for Las Vegas.”

The A’s would be the fourth and final major league team to leave Oakland. The NBA’s Warriors moved to San Francisco in 2019, and the NFL’s Raiders moved to Las Vegas in 2020. The NHL’s California Golden Seals moved from Oakland to Cleveland in 1976.

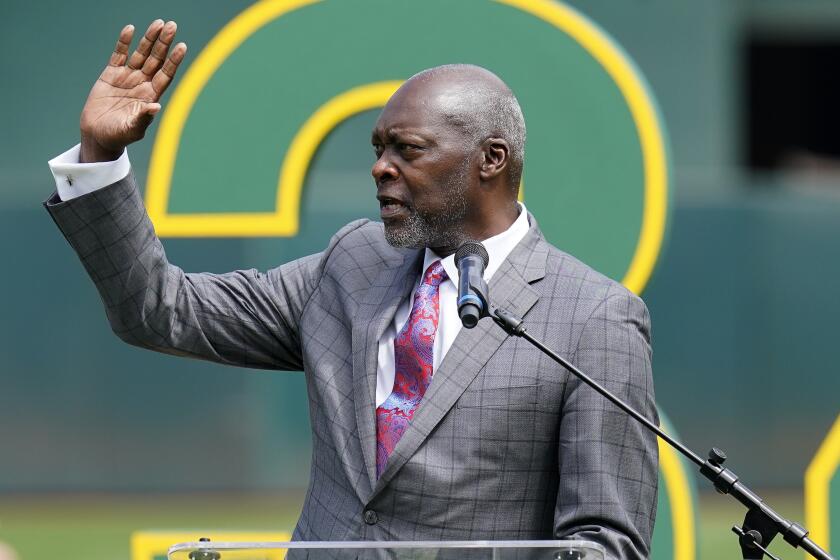

Oakland, the only major league city on the West Coast with a large Black community, is about to lose the A’s and that doesn’t sit well with former players.

The A’s have targeted 2028 for the grand opening of their Las Vegas ballpark. Their lease at the Oakland Coliseum expires after next season.

Among the A’s options for a home in the interim: a short-term lease to stay at the Coliseum, as the Raiders did before they left for Las Vegas; Oracle Park in San Francisco, where the Giants play; and the triple-A ballparks in Las Vegas and Sacramento.

It would not be unprecedented for a departing team to play in multiple stadiums over the course of a season. In 2003-04, the final two seasons of the Montreal Expos, the team split its home games between Montreal and San Juan, Puerto Rico.

“My hope is we find an 81-game home for the A’s,” MLB Commissioner Rob Manfred said.

The only other major league team to relocate in the last half-century: the Expos, a team reluctantly bought by MLB after the league’s failed attempt to kill the team, moved to Washington, D.C., in 2005 and then were sold to a local family. In 1972, the Washington Senators became the Texas Rangers.

To the A’s owners, the relocation vote was less about blessing a slam-dunk move and more about grabbing a lifeline extended by Las Vegas rather than prolonging the never-ending search for a new ballpark in Oakland.

“The Oakland thing isn’t sustainable,” Dodgers chairman Mark Walter said. “They’ve worked on that a long time. You can’t play in that stadium.

“They couldn’t get approval [from the city of Oakland]. They tried. This wasn’t some head fake. That wasn’t a quick decision.”

With the NBA expected to expand to Las Vegas soon, the A’s could prosper in a town where minor league baseball draws big crowds — or quickly sink to the No. 4 team in a smaller market with an ever-expanding menu of entertainment options.

“I do find it interesting,” Major League Baseball Players Assn. chief Tony Clark said during the World Series, “that, amid the conversation and dialogue around finances, rather than staying in the sixth-largest market, they’re moving to a market that may have them in a perpetual cycle of receiving revenue sharing.”

In Las Vegas, a city for so long shunned by pro sports because of its association with gambling, three major teams have landed within a decade: the Stanley Cup champion Golden Knights, who started play in 2017, followed by the Raiders and now the A’s.

Manfred called Las Vegas “one of the two strongest open markets in the United States.”

The cost of the Las Vegas ballpark is estimated at $1.5 billion, with public financing covering $380 million and Fisher covering the rest. A Nevada teachers union is pursuing a referendum and a lawsuit to try to block some or all of the public financing. If the union were to succeed on either front, Fisher would not be stopped from moving to Las Vegas but would have to cover the financing gap.

Fisher is believed to be looking for minority investors, hoping to generate $500 million toward stadium costs by valuing the A’s at $2 billion and selling 25% of the team.

At the start of the 2023 season, when the A’s fielded a team with the lowest payroll in the majors, Sportico valued the team at $1.3 billion.

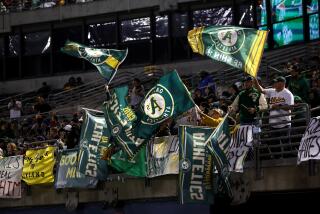

The A’s lost 112 games this year, the most in the majors. They were the only major league team to sell fewer than 1 million tickets, with fans reluctant to support a management that raised ticket prices, trashed the Coliseum, claimed only a new stadium could provide the revenue to deliver a consistent winner, and repeatedly failed to deliver a new stadium.

Yet the biggest winner Thursday was the Giants, who soon will have one of the top 10 media markets in the United States all to themselves. When the A’s wanted to build a ballpark in San Jose, the Giants declined to yield their territorial rights to Santa Clara County, essentially blocking the move.

Walter said he did not believe the Giants’ monopoly in Northern California — and the financial benefits that would come with it — would threaten the Dodgers in their competition with their longtime rivals in San Francisco.

“I think of it as on the field, and I understand that money helps,” Walter said. “We’re the No. 1 revenue team in the National League.

“I’m not against the Giants making money.”

In a two-decade search, the A’s also explored ballpark opportunities around the Coliseum site, in downtown Oakland, at the Oakland waterfront, and in suburban Fremont — and, starting in 2021, Las Vegas.

Fisher and Manfred each said the A’s had exhausted all options for staying in Oakland, a contention sharply disputed by Oakland Mayor Sheng Thao. The mayor said Oakland had obtained commitments for more public funding than the A’s originally had sought.

“There was never a deal in Oakland,” Manfred said.

“We did everything we could to try to find a solution there,” Fisher said.

From late April, the A’s negotiated exclusively in Nevada. Within two months — and with the assistance of an army of Nevada lobbyists —the A’s had secured the public funding for a Las Vegas ballpark.

Manfred said MLB owners waived a relocation fee that could have cost Fisher hundreds of millions for two primary reasons: one, in recognition of the $1 billion that Fisher had committed toward a new ballpark and, two, to bolster support for public funding in Nevada and underline the league’s commitment to helping the A’s succeed in Las Vegas.

Warriors owner Joe Lacob has long said he would buy the A’s and keep them in Oakland, and Thao said other parties that were “viable and willing to buy” had told her they would do the same.

“But you can’t buy a team that’s not for sale,” Thao said.

The billionaire owner of the Oakland A’s ripped off his home-team fans and is staging a ripoff of Las Vegas, showing that civic leaders never learn that stadium subsidies never pay off.

Manfred has long said MLB would expand only after the A’s and the Tampa Bay Rays had resolved their pursuit of new stadiums. With the A’s moving to Las Vegas and the Rays reaching a tentative agreement on a new ballpark on the site of their current home, MLB now can explore options for two new teams.

Cities of interest include Nashville; Montreal; Salt Lake City; Portland, Ore.; and Charlotte and Raleigh, N.C.

Oakland could be an option too, but MLB would not consider the city and any prospective owners there unless the bid explained how a new ballpark would be built and who would pay for it.

“The A’s branding and name should stay in Oakland and we will continue to work to pursue expansion opportunities,” Thao said in a statement Thursday. “Baseball has a home in Oakland even if the A’s ownership relocates.”

Said Manfred: “When and if we have an expansion process, every city that’s interested in having an expansion franchise will have an opportunity to participate.”

The expansion fee is expected to be at least $2 billion, so revenue from two expansion teams would provide the current 30 teams with more than $133 million each — no small matter at a time when the collapse of the cable model threatens to disrupt and diminish the broadcast revenue stream upon which teams have long relied.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.