Commentary: Bobby Knight was a bully who really didn’t like John Wooden

News of Bobby Knight’s death last week produced thousands of words, with descriptions ranging from sadness to admiration to disgust.

Many even wrote that he was an “enigma,” which is a mysterious person, somebody difficult to understand. That was rationalizing. It was also incorrect.

John Feinstein, who wrote a best-selling book about Knight years ago, hit closer to the truth last week in his assessment of a man who gave him complete access for the book and then hated it so much that he barely spoke to Feinstein for the rest of his life. That’s because Feinstein told the truth. In his story the day after Knight died, Feinstein wrote of the infamous college basketball coach that “many swore by him and many swore at him.” Feinstein was being kind. It never was 50-50.

Knight was never an enigma. He was a jerk and a bully. To some, those in the school of “only wins and losses count,” his behavior was to be forgiven by his marvelous coaching record. Throw a chair, berate hundreds of referees, verbally assault just about anybody who played for him — or against him. Tell female sportswriters that their only worth is “to have babies and make bacon,” tell a sports official from Puerto Rico that his country’s only value is to “grow bananas” — that’s all OK to those who subscribe to “Just win, baby.”

Bobby Knight, one of college basketball’s greatest coaches, whose volatile temper and behavior often overshadowed his game-time genius, has died.

Over time, the timid or those wired to avoid confrontation just stayed out of his way. Others stopped fighting back or trying to get him to see himself. He wore them down.

That’s what bullies do.

One person who seemed to survive this all, a genuinely kind and soft-spoken man, who had the hardest job in sports journalism in America, was Bob Hammel, longtime sports editor and sports columnist of the local paper in Bloomington, Ind., where Knight rose to fame at Indiana University. Hammel and Knight battled early, then gradually reached a working truce and became lifelong friends. That’s not an ideal situation for any journalist, but Hammel’s choice was to get on the bus or get out of town. Indiana basketball was the only sports show in town — ever watch Indiana football? — so Hammel stayed and did his best. If there were a Nobel Peace Prize for sports journalism, the first one would go to Hammel.

Even that relationship was rocky. In the end, everything was always about Knight.

Years ago, Hammel was honored at a special dinner in Bloomington. It was a great night, lots of people showed up. Hammel’s sportswriting friends from around the country flew in. There was a speakers’ table and Knight, as well as several sportswriters, were seated there, scheduled to give tributes to Hammel.

The speakers were there for one reason. To honor Hammel. To praise him, kid him, tell stories about him. Then Knight got up, said almost nothing about Hammel and started berating one of the sportswriters at the table about something he had written a year or so earlier. It became a lecture on the evils of sportswriting and the incompetence of the writer. The mood in the room went from warm and joyful to uncomfortable frowns and embarrassment.

I’m relieved to have Bobby Knight out of my life. I just hope Dad understands.

By the time the sportswriter had a chance to get up and hit back a bit at Knight, or joke about it, or attempt to loosen up the room again, Knight was gone — out the back door — and Hammel’s night was much less festive.

That’s what bullies do.

For those who wish to maintain an image of Knight as merely a tough guy who thought he had to be unlikable and dictatorial to win, there is one facet of the man that says it all.

He didn’t like John Wooden.

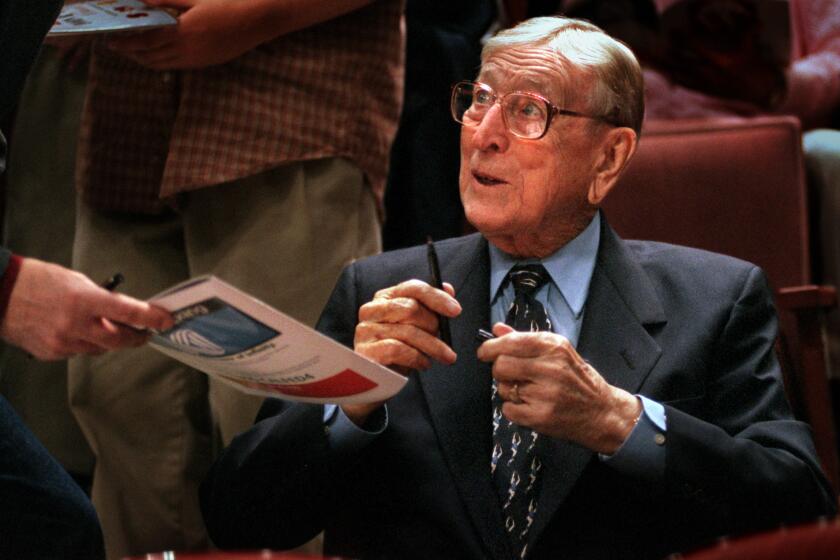

That puts Knight in a fractional minority of sports fans and humanity in general. Wooden didn’t set out to be universally loved. He just was. He won 10 NCAA titles at UCLA and spent most of his life giving credit to others for that. He was scholarly, thoughtful, generous, interesting and a great basketball coach. Knight lived and died basketball. Wooden lived and died life.

It’s been 10 years since the death of UCLA basketball coach John Wooden and we still miss his simplicity and grace, writes columnist Bill Plaschke.

The berating of the sportswriter at Hammel’s dinner was directly connected to Wooden. In 1993, Indiana’s Calbert Cheaney won the John Wooden Award as the nation’s best basketball player. It was an award coveted and prestigious. A big part of the thrill for the winner was getting to go to Los Angeles to meet and spend time with Wooden, who treated each honoree like deity.

But Cheaney didn’t attend and reporting showed later that, while the excuse from Indiana had been that he had school work responsibilities, he had spent the evening of the Wooden Award at a school-sponsored basketball event. A sportswriter saw Knight’s hand in that, wrote about it and that same sportswriter was berated at the Hammel dinner.

Wooden stopped coaching in 1975, with his 10th NCAA title. Knight got to Indiana in 1970 and won three NCAA titles. Their coaching paths didn’t cross much. But Knight took several opportunities to be critical of Wooden, saying publicly, “I‘m not a fan of John Wooden,” and saying that his reason was the Sam Gilbert recruiting scandals of the early 1980s. That NCAA penalty came more than five years after Wooden retired. But Gilbert was certainly around in Wooden’s time and has remained an eyesore on the Wooden legacy.

But it turned out that Knight’s concern for UCLA’s recruiting practices was not the main reason for his stated antipathy toward Wooden. It was much more petty than that.

The dark side of the UCLA basketball dynasty

Rick Majerus was a great college basketball coach. He took his Utah team to the NCAA final in 1998. He was a protege of Knight and an admirer of Wooden. One night, well into one of those dinners of fine food and finer storytelling, Majerus answered the puzzling question of why Knight bad-mouthed Wooden.

It had less to do with Gilbert and more to do with Knight’s longtime friend and mentor, Pete Newell, Majerus said. It was about Wooden having eclipsed Newell in success and stature. Newell was the coach at California, and a great one, even beating UCLA frequently. But those were the years when Wooden was winning everything and Newell was left in the background. As Majerus put it, Newell didn’t care, but Knight did. Newell was Knight’s guy. Wooden wasn’t.

It was as simple as that. Wooden was stealing Newell’s thunder, and Knight didn’t like it.

That, of course, was silly and petty, probably even a little bit evil. But that was also Bobby Knight, who made a bit of a campaign of it for years.

That’s what bullies do.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.