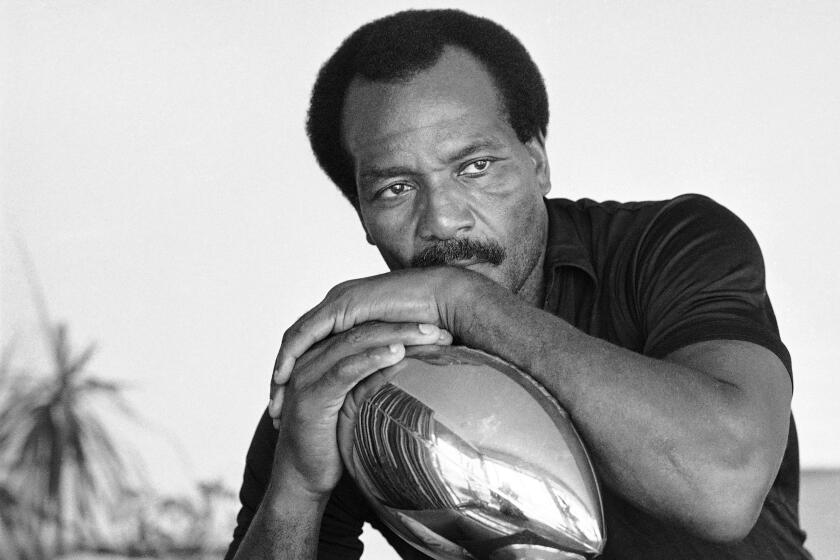

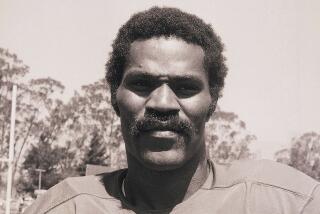

Jim Brown, football great, actor and civil rights activist, dies

A multi-talented athlete cast in the mold of the legendary Jim Thorpe — he’s in three halls of fame — Jim Brown was best known as a football player. Perhaps the football player. A fullback for the Cleveland Browns, he was regarded by many as the greatest pro football player of all time.

But at the height of his career he quit the game, saying he needed greater mental stimulation in his life, and threw himself into his budding acting career and the social activism that made him an influential figure during the civil rights era.

For the record:

1:24 p.m. May 23, 2023This obituary on Jim Brown states that he placed fifth in the decathlon at the 1956 U.S. Olympic trials. He did not compete in the 1956 U.S. trials.

A man of many facets, Brown died late Thursday at his home in Los Angeles, his wife, Monique, announced on Instagram. No cause was given. He was 87.

“To the world he was an activist, actor and football star. To our family, he was a loving and wonderful husband, father and grandfather. Our hearts are broken,” she wrote.

“I hope every Black athlete takes the time to educate themselves about this incredible man and what he did to change all of our lives,” Lakers star LeBron James said on social media. “We all stand on your shoulders, Jim Brown. If you grew up in Northeast Ohio and were Black, Jim Brown was a God.”

In his football career, the Browns won the NFL championship in 1964, before the creation of the Super Bowl, and he led the league in rushing eight times, failing to gain at least 1,000 yards only in his rookie season. He was the league’s most valuable player three times and at his retirement held the records, among many others, for most rushing yards in a season (1,863) and a career (12,312).

Jim Brown was certainly a U.S. icon as one of the NFL’s greatest players, an activist, an actor, an icon, but he also had difficulties in society and was not worshipped by all.

Those marks have long since been broken, but when Brown was playing, the NFL season was 12 games for his first four seasons, then 14 for the next five. Today’s pros play a 17-game regular-season schedule. And Brown’s per-game record of 104.3 yards rushing appears as unassailable now as it did then. No other running back has even cracked 100 yards.

Brown didn’t just run from scrimmage, though. He was an excellent receiver out of the backfield, catching 262 passes for 2,499 yards and 20 touchdowns, and he returned kickoffs for an additional 628 yards.

More impressive than his numbers, though, was his style. At 6 feet 2 and 232 pounds, he was a speedster who loved contact. If he couldn’t run past a defender, he’d try to run over him — and often did.

“Jim Brown was a combination of speed and power like nobody who has ever played the game,” Dick LeBeau, a Hall of Fame defensive back with the Detroit Lions and later one of the longest-serving coaches in league history, told Sports Illustrated 50 years after Brown had walked away from the game.

“Obviously, arm tackles were not going to slow him down, but he was so elusive. ... He was so good at setting you up, then making you miss. You just didn’t know if you were going to get a big collision or be grabbing at his shoelaces.”

And, said John Mackey — who, like Brown, played his college football at Syracuse and then went on to a 10-year career as a tight end for the Baltimore Colts and San Diego Chargers — “He told me, ‘Make sure when anyone tackles you he remembers how much it hurts.’”

Football, though, was just one of the athletic things Brown did well. At Manhasset High School on Long Island, N.Y., he also played lacrosse, baseball, basketball and water polo, and ran track. As a sophomore at Syracuse, he was the second-leading scorer on the basketball team, competed in track and field and continued to cultivate his love for lacrosse, which he preferred to football.

One spring day in the mid-1950s, Lefty James, Cornell’s football coach, took in a Syracuse-Cornell lacrosse game and was surprised to see Brown, the All-American running back, leading the Syracuse team.

“Oh, my goodness,” he sputtered, “they let him play with a stick!”

In track and field, they let him play with a discus, a 16-pound shot and a javelin. In 1956, even though he was only slightly familiar with some of the events, Brown finished fifth at the U.S. Olympic trials in the decathlon, the 10-event competition considered by many as the truest test of athleticism.

Although that finish qualified him for the Olympics, he skipped the Melbourne Games to concentrate on football, the sport offering him the most lucrative future. By the time he graduated from Syracuse, he had accumulated 10 varsity letters — three each in football and lacrosse, and two each in basketball and track — and was an All-American in lacrosse as well as football.

He is in both the pro and college football halls of fame, and the lacrosse hall as well. In 2019, in celebration of 150 years of college football, 150 judges for ESPN named him the best college player ever. He finished his collegiate career at Syracuse with 2,091 yards and 26 touchdowns, and the Syracuse Carrier Dome has an 800-square-foot tapestry showing Brown in football and lacrosse uniforms, identifying him as “Greatest Player Ever.”

His statue stands outside Cleveland’s FirstEnergy Stadium.

No one ever referred to him as the “greatest actor ever” — in most of his roles he played a version of himself, brooding and intense, yet bold and incisive — but he appeared in more than 30 films during his 50-year cinematic career. And it did have its moments. In 1969, for instance, he was billed over co-stars Raquel Welch and Burt Reynolds in “100 Rifles,” and his love scene with Welch in that movie was hailed, inaccurately, as filmdom’s first featuring an interracial couple.

Brown, who was making slightly more than $60,000 a season at the peak of his NFL career, had already made one movie and was working on his second when he decided he was through with football. He had accepted an off-season role in “The Dirty Dozen,” a big-budget, multistar movie about hardcore military prisoners offered a suicide mission against a French chateau held by top Nazi officers during World War II.

Filming, however, was delayed by weather problems, and when his team congregated for training camp in 1966, Brown was still in England, working on the movie.

Movies: Spike Lee documents the athletic and civic achievements of a controversial American figure.

That did not sit well with Browns owner Art Modell, who announced he was fining his star $100 — the equivalent of about $935 today — for every day he missed camp.

Abruptly, Brown called John Wooten, his friend and teammate, telling him he was retiring and to wish the team well. The next morning, the 30-year-old Brown, wearing Army fatigues and sitting in a high director’s chair in front of a tank on the movie set, announced his retirement to the world.

“My original intention was to try to participate in the 1966 National Football League season,” he said. “But due to circumstances, this is impossible.”

A day later, he told Tex Maule of Sports Illustrated: “I could have played longer. I wanted to play this year but it was impossible. We’re running behind schedule shooting here, for one thing. [And] I want more mental stimulation than I would have playing football. I want to have a hand in the struggle that is taking place in our country and I have the opportunity to do that now. I might not a year from now.”

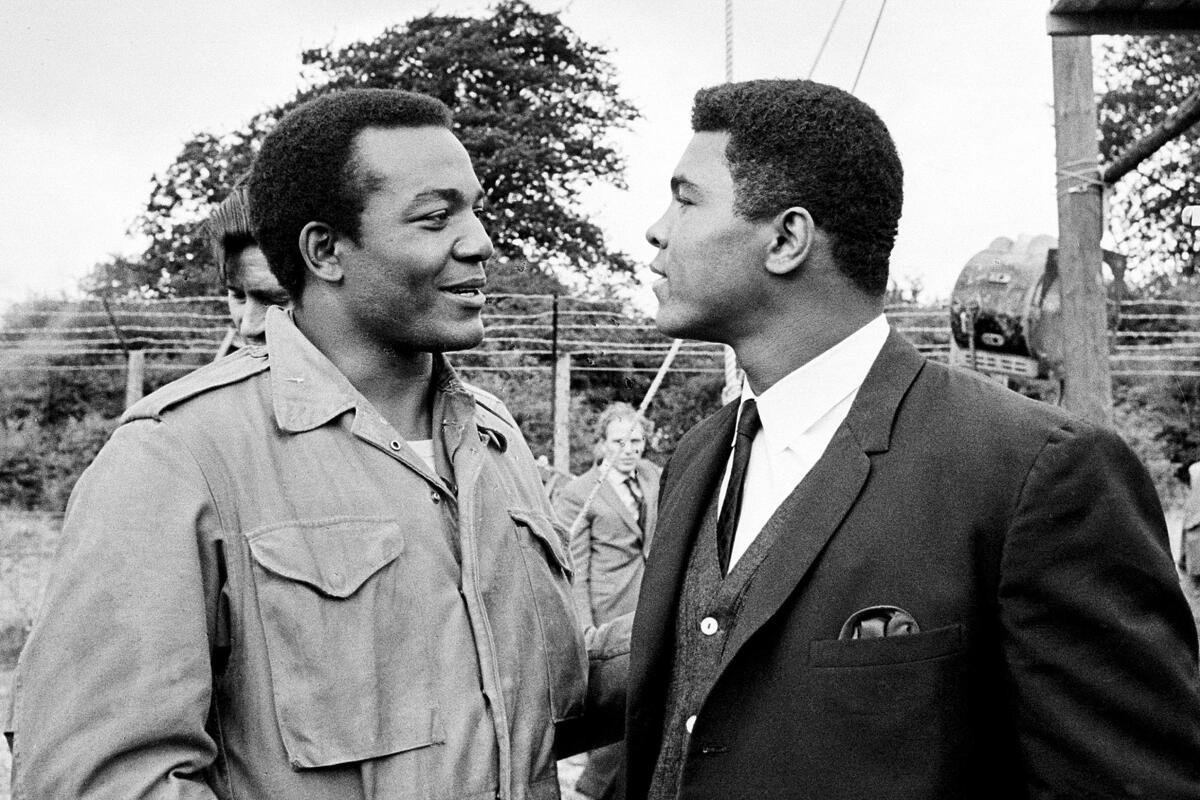

By then, he had already formed the Black Economic Union, a group dedicated to the belief that economic development was the key to equality for Black Americans. Among its many high-profile members and spokesmen were Bill Russell of the Boston Celtics and Muhammad Ali, the once and future heavyweight boxing champion. Years later, Brown told the Cleveland Plain Dealer that more than 400 businesses had been launched with the help of the BEU.

In 1967, when Ali refused to be drafted into the military in protest of the Vietnam War and was stripped of his title, Brown gathered an impressive group of successful Black athletes such as Kareem Abdul-Jabbar to publicly support Ali.

In 1988, living in Los Angeles, Brown founded Amer-I-Can, a national organization to help rehabilitate gang members and former prisoners. According to the Amer-I-Can website, the program aims to enable individuals “to meet their academic potential, conform their behavior to acceptable societal standards, and improve the quality of their lives by equipping them with what they need to confidently and successfully contribute to society.”

Brown often brokered peace deals between rival street gangs and led meetings with at-risk young men at his home in the Hollywood Hills as well as in Cleveland and in other cities with Amer-I-Can chapters.

He appeared as a color analyst on NFL telecasts for CBS along with Vin Scully and Hall of Fame coach George Allen, was the first Black American to announce a televised boxing match in the U.S. — Ernie Terrell’s 15-round decision over George Chuvalo in 1965 for a portion of the heavyweight title — and later served as color commentator for Ultimate Fighting Championship events. He is also credited with suggesting to Bob Arum, then a little-known lawyer, that he seek a new career in boxing. Arum took that advice and became the most influential boxing promoter of his day.

For an athlete with such startling moves, however, Brown couldn’t seem to get out of his own way in daily living. The man who proposed to help young men avoid trouble knew all about it, firsthand.

Brown married Sue Jones in 1959 and they had three children, but it was a union fractured by Brown’s extramarital affairs and they divorced in 1972.

In his autobiography, “Out of Bounds,” written with Steve Delsohn, Brown acknowledges a robust sex life.

His bedroom activities, though, often led to complications. In 1965, still married, he was arrested in a hotel room on suspicion of assault and battery against his 18-year-old girlfriend, Brenda Ayres. He was acquitted, but a year later he faced a paternity suit filed by Ayres.

In 1968, he was charged with assault and attempted murder after another girlfriend, model Eva Bohn-Chin, was found injured under the balcony of his second-floor apartment. Brown claimed that Bohn-Chin had climbed over the balcony railing during a heated argument over his alleged affair with feminist Gloria Steinem. The charges were dismissed when Bohn-Chin refused to cooperate with the prosecution, but Brown was fined $300 for hitting a deputy during the investigation.

In 1975, Brown was sentenced to a day in jail, placed on two years’ probation and fined $500 for beating and choking a golfing partner.

And over the years, there were other women, other incidents and other children — some recognized by Brown as his, some not.

Regina King’s “One Night in Miami” does not explore the multiple domestic violence charges later brought against NFL great Jim Brown. But Black storytellers often face a purity test regarding historical accuracy that other filmmakers escape.

In 1977, he married actress-producer Monique Gunthrop. They had two children and remained married until Brown’s death. In 1999, after an argument with Gunthrop over his alleged infidelity, Brown was arrested and charged with threatening her with bodily harm. He also was found guilty of vandalism for striking her car with a shovel.

He was sentenced to three years’ probation, a year of domestic violence counseling and 400 hours of community service or 40 hours on a work crew, and was ordered to pay an $1,800 fine — all of which he ignored.

In 2000 he was sentenced to six months in jail for ignoring the court-ordered punishment. He said he had purposely chosen the jail time.

“I could have been a domesticated African and taken what the judge gave me,” he told the Washington Post. “But I chose to be a man of character.”

In jail, Brown refused to eat solid food but otherwise was a model prisoner and was released after three months, 25 pounds lighter.

His freewheeling lifestyle nearly cost him his niche in the College Football Hall of Fame in Atlanta. Qualifications include a clause that a candidate be worthy as a citizen, and that kept Brown out for years.

He finally was inducted in 1995, 38 years after completing his college career.

Brown is survived by his wife and children.

Kupper is a former Times staff writer.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.